South Korean collector Higgin Kim: ‘People are genuinely rough. Art works like a tenderiser’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There are many collectors of contemporary art who specialise in just one medium or style or coterie of artists. Higgin Kim, the chair of the Byucksan Engineering and Construction Company in South Korea, is not that kind of collector. “I don’t care about art histories and a scholastic sort of approach,” he says in his capacious office high above Seoul’s Guro district, when asked to define his taste. “I just want to enjoy my life.”

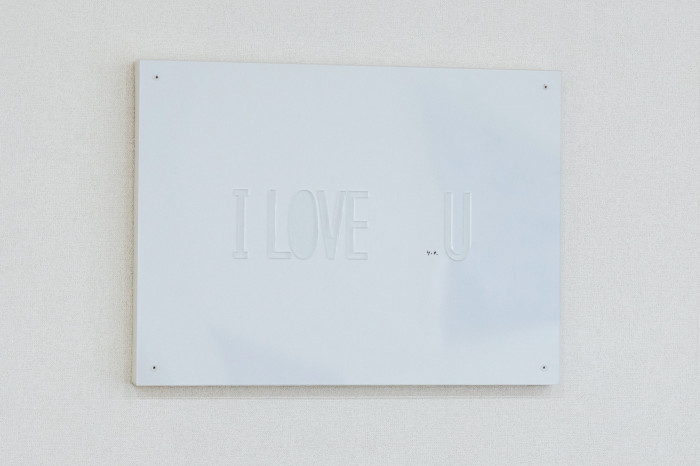

The 400 works arrayed throughout Byucksan’s headquarters in the Pan-Pacific building suggest a man with unbounded curiosity and a zest for new ideas. There is a Nam June Paik robot sculpture assembled from TV monitors and other tech devices; an amber-coloured glass horse by Shin Sang-ho (next to a window, to catch sunlight); an intricate spiderweb — like a tangle of rope suspended in a box — by Tomás Saraceno. (“What in the devil is this?” was Kim’s reaction when he saw the latter at Art Basel.) A James Turrell hologram hangs behind his receptionist’s desk and behind his is a Yoko Ono Plexiglas edition with small text reading “I LOVE U”.

Wearing his trademark bow tie with a tan suit, Kim, 76, has the look of a gentleman scholar, or perhaps even an Indiana Jones-style adventurer. He is erudite and soft-spoken, which lends a certain intrigue to his talk about the cut-throat construction industry. “People are genuinely rough,” he says, “so I want to share artworks. The art works like a tenderiser.” As classical music plays in the background, he jokes about some of Byucksan’s 1,200 employees discussing, with a measure of exasperation, how he pushes culture on them, with lectures and “points” that employees can spend to attend cultural events. “Once in a while we teach them about the paintings and classical music and things like that,” he says.

There is a rich recent history of South Korean conglomerates spending big on art in Seoul as part of their philanthropic activities. Samsung has its Leeum and Ho-Am museums in the capital region, filled with ancient Korean and global contemporary material; the Amorepacific beauty empire inaugurated a David Chipperfield-designed headquarters and museum in 2017; the energy company ST International went with Herzog & de Meuron for its own place last year.

Kim has taken a different tack. The art is all his own, not Byucksan’s, and he has decided against building it a dedicated home. “I have designed the museum twice already. I have a piece of land to build a museum. But to maintain a museum is very costly.” Some who have embarked on that path have had financial issues and had to offload art. “You can’t do that,” he says. “You have to learn from history and other countries.”

Kim’s own history spans post-second world war Korea. He was born in Seoul in January 1946, just months after the country’s liberation from Japan, and in 1948 his father started the company, before the family fled to Busan during the Korean war. They returned to Seoul when Kim was 10; later he attended Miami University in Ohio. After mandatory military service, he worked for the family business and found his way to Saudi Arabia in 1973 for about a dozen years. “There I made my first million dollars,” Kim says. “I was 31. Nothing to spend it on. There was nothing there.” Half his time there was spent working for arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi’s Triad International, looking after Asian business in investment and trade, he says.

Returning in 1985 to Seoul, and to the family business, Kim began amassing an art collection with his wife, Sohyung Lee Kim, though Khashoggi’s love of opulence seems not to have rubbed off on him. “Within the budget, you have to find the best,” he tells me. “That’s the principle of the collection.” They focused on contemporary art because the sky-high prices of Impressionism and modernism seemed beyond their reach. (“I could sell this,” he says, gesturing at the art on the walls, “and buy one piece.”)

His approach was to buy one or two pieces a month, and the collection now has more than 1,000 works. While Kim is open to trades, he has sold only once, when a relentless dealer convinced him to part with an Anselm Kiefer. By contrast, Kim did sell off a number of subsidiaries while fighting to stay afloat in the late-1990s Asian financial crisis. “I was so dumb,” he says. “We knew it was coming. I didn’t do anything about it. And I didn’t know what it meant. I thought it was somebody else’s problem.”

Even years after their purchase, many works continue to have a deep resonance for him. An early buy, a Salvador Dalí print of the crucifixion, “never bores” Kim. (“I was born a Christian, never missed Sunday,” he says.) After his first wife died, he began seeing his current wife, art dealer Ihn Yang Kim, 12 years ago, while he was on the steering committee of the Korea International Art Fair (which runs alongside Frieze Seoul next week). She sold him a James Casebere photograph and a Liam Gillick wall piece that hang in a conference room. “I was dating my wife, so I had to buy some artworks from her gallery,” he says. “That also helped our collections.”

When not thinking about art, there are philanthropic and community projects to keep him busy. For instance, he loans three rare instruments — two violins (one a 1683 Stradivarius) and a cello — to Manhattan’s Sejong Soloists ensemble. “I don’t have a talent for painting, or playing different instruments or singing, but I really appreciate their professions,” he says, and supporting artists comes with benefits. “It’s fun to talk with them. Nowadays it’s another way to meet young people.”

Kim has given an art-buying budget to his son, who works at Byucksan, and his son’s wife, an artist, and their recent acquisitions include a radiant still life of fruit by photographer Wolfgang Tillmans that hangs near the elevators. “I try not to buy,” Kim says, a hint of mischief in his voice. “It’s difficult.”

Comments