Lawyers keep an eye on copyright risk with generative AI

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Lawyers are paying close attention to the proposed regulation of generative artificial intelligence in Europe, the US and China as their clients contend with the unclear risks of violating intellectual property rights.

These AI platforms are trained using existing works and can then produce new works in response to a prompt. And Ceyhun N Pehlivan, co-leader of Linklaters’ telecommunications, media and technology and IP practice in Madrid, points out that the generative AI platforms on the market — ChatGPT, AlphaCode, GitHub Copilot, and Bard — “are collecting all the information out there, this includes texts, images, and videos, and the problem is some of those are protected by copyrights”.

At the same time, it is not clear what steps generative AI developers and users might take to enforce their own IP rights for whatever is created by these new tools. “It is very difficult to answer that question,” Pehlivan says.

As a result, Pehlivan, and other IP lawyers trying to identify best practice in this uncertain environment, are paying close attention to proposed generative AI regulatory schemes that are under consideration across the world.

They expect the strictest rules adopted by the European Union, the US, or China to set a globally accepted standard.

“If I need to comply with both US and EU law, and one of them lets me do it, and the other one doesn’t, I still can’t do it,” says Mark Lemley, a Stanford Law School professor and counsel at Lex Lumina, which is defending London-based Stability AI and other generative AI companies against copyright infringement claims filed by picture agency Getty Images.

The EU might be first to enact sweeping generative AI regulations — the bloc is working on an AI Act that is due to be finalised next year. Copyright was not addressed in the initial drafts but, last month, the European parliament added a clause that requires generative AI developers to “make available summaries of the copyrighted material that was used to train their systems”. However, what the “summaries” should include is not specified, Pehlivan notes.

Under the EU Copyright Directive, which took effect in 2019, it falls to copyright holders to thwart use of their data if generative AI tools or other types of web-searching software can find it, Pehlivan says. It “is permitted” to train a generative AI engine using lawfully accessed works, provided that the rights holder has not opted out, he says.

In the UK, by contrast, unfettered data mining from web sources is barred, points out Pehlivan — except for non-commercial purposes. When the UK’s Intellectual Property Office, in an effort to tweak the rules to accommodate the new technology, proposed an exception to that rule for generative AI, the plan triggered such a big backlash from the creative industries that it was aborted. Whatever eventually becomes effective will not include such a loophole.

In the US, the “fair use doctrine” in its copyright law has raised expectations that there will be only a minimal risk of generative AI developers and users infringing copyrights, according to Lemley.

A “bigger danger” looms for users of GAI if the output appears “too similar to something . . . on [the] input side,” Lemley says. But that only happens with existing GAI systems if the user asks for the output to be similar to a specific input, he notes.

“If you go ask ChatGPT to write me a children’s story about kids who go to a wizard school, it’s not going to write anything close to Harry Potter,” he says. “But if you say: ‘Write me a children’s story about kids who go to a wizarding school that begins’ and you give it the first paragraph of Harry Potter, it will actually spit out several pages of Harry Potter.”

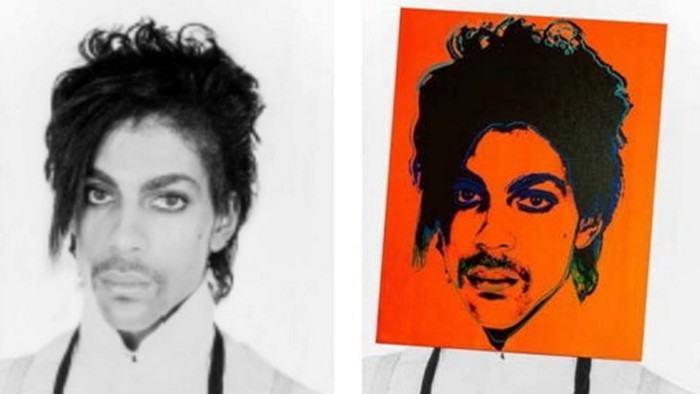

Another old case that may have a bearing on the use of this new technology concerned Andy Warhol paintings. The US Supreme Court ruled last month on a case between the late artist’s estate and a photographer who shot a portrait of the late singer Prince. The justices ruled that Warhol had infringed the photographer’s copyright when he made and sold an artwork based on the photo, in a ruling that hinged on Warhol’s work being insufficiently “transformative”.

The Copyright Alliance, which advocates for rights holders, noted that “it’s not hard to see how the Court’s treatment of transformative use could impact artificial intelligence developers’ approach to their unauthorised copying and ingestion of copyrighted works for training purposes”.

Amid the uncertainty about which rules will become effective and how courts will interpret them, vigilance over contractual obligations will go a long way to providing protection for generative AI users and developers, says Jennifer Maisel, an IP lawyer and member of Rothwell, Figg, Ernst & Manbeck in Washington, DC.

As a first step for users, Maisel advises: “Look at your agreement with the software provider,” to determine what warranties exist about the content that the generative AI was trained upon — and whether it reassures that guardrails are already in place to prevent third-party copyright infringement claims.

Given the fierce competition for market share among generative AI tool developers, she believes that such clauses will start turning up in users’ contracts. “We’ve seen this in other software contexts,” she says, “liability tends to be pushed to the software owner.”

But if, or while, such assurances are absent, she believes users should take “risk-mitigation measures” including establishing audits or indexes, as much as possible, for the sources their generative AI tool trained upon before spitting out its creation.

Comments