Inside Wuhan: China’s struggle to control the virus — and the narrative | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A seemingly endless line of masked patients fills a crowded hospital corridor. The sick are bundled in heavy coats and scarves in the icy, fluorescent light as they wait to see a nurse or doctor. These photographs, stealthily taken on Hao Jun’s mobile phone, are a silent record of the crisis that engulfed Wuhan just two months ago.

Sitting with Hao under a camphor tree on a warm spring day in the city’s Liberation Park last week, the images feel almost unreal. On April 8, Wuhan was liberated after a 76-day quarantine that had trapped 11 million residents within its boundaries. Now, fields of wild flowers have bloomed across the park and a few visitors stroll through the sycamores.

But the pain of two months ago never seems far from Hao’s mind. From early February, he — like most residents in the city — was surrounded by affliction and death. He spent days accompanying family and friends to hospitals in search of beds and medicine. Most eventually recovered but several died of the virus, among the more than 3,800 fatal cases in Wuhan.

Throughout the chaos of the outbreak that started in late January, Hao spent hours secretly taking photos, keeping a citizen’s record of what he described to me as “disorder” and “madness”.

Hao, in his late forties, is one of a small but tight-knit group of dissidents based in Wuhan who took it upon themselves to document the earliest days of coronavirus, a period that has become a closely guarded secret by China’s Communist party.

The city, a sprawling metropolis at the heart of central China, is ground zero for the outbreak now sweeping the planet, with 2.5 million infected globally and 165,000 dead at the time of going to press.

Many scientists suspect the disease may have been first transmitted to humans in a local wet market, where wildlife such as bats — which can host highly transmissible viruses — was once sold as a delicacy.

Wuhan’s place at the geographic centre of the country and at a number of key junctures in history has also made it a hub of political awareness. It hosts some of China’s top universities and, over the years, has gained a reputation as an outpost for dissidents, who have faced increased government surveillance since the outbreak began.

Even so, Hao’s willingness to speak frankly about gross mismanagement of the disease by the Communist party puts him in a tiny cohort. Local officials are accused of not only reacting slowly in late December, but also of aggressively silencing those who tried to raise concerns early on. Many people who watched loved ones overcome by the illness have felt deep anger and frustration.

Wuhan’s official death count was revised upward last week by more than 50 per cent, vindicating those who argue that the state under-reported the number of deaths. Many experts still question whether the official data is accurate. Office workers, state employees and dissidents alike have asked why their lives were so suddenly upended by the outbreak — and whether there was a better way of handling it.

“Of course it could have been different,” says Hao, who notes that his activities are monitored closely by the local police and has asked to use a pseudonym. “Different leaders could have done things differently. They would have protected the people instead of just protecting themselves . . . We [record what’s happening] because this is the only way people can know what the real situation is. We have to do this ourselves because you cannot rely on the government news.”

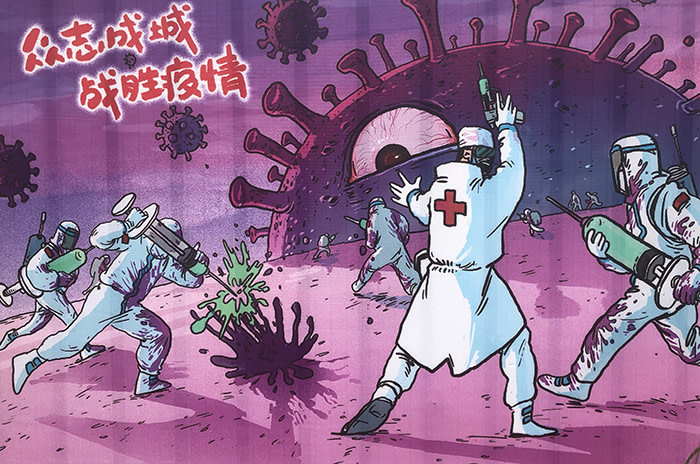

I return to my hotel room in central Wuhan to find a package from the local government waiting for me. They have sent foreign journalists two large bottles of hand sanitiser, 20 masks and a 55-page comic book dedicated to sanitation. In one cartoon, a grinning bottle of ethyl alcohol reminds readers to wipe down their phones up to four times a day.

But the main item in the care package is a hastily bound white booklet with a cover that reads simply: The Chinese Way. Most of the content is a selection of state-media stories about the pandemic, in seemingly random date order. But it also includes a carefully curated timeline of the crisis in China — a window into the Communist party’s construction of its narrative around the outbreak.

The story begins on an unspecified date in late December when Wuhan’s Centre for Disease Control detects “cases of pneumonia of an unknown cause”. By January 7, President Xi Jinping has given instructions on responding to the oncoming epidemic. On January 20, a veteran doctor warns the country of human-to-human contagion, while the first patients — an elderly man surnamed Wan and his wife — are successfully discharged from the hospital.

In February, the official timeline has Chinese experts and officials spreading their knowledge across the globe, advising Estonia on the 17th and briefing the crown prince of Abu Dhabi on the 25th.

As fear and contagion began to run wild in the US and Europe in March, the booklet suggests that China’s story was drawing to a neat conclusion. The entry for March 24 says: “Xi stressed that the international community has already recognised that China made enormous sacrifices in the fight against Covid-19 and bought precious time for the world.”

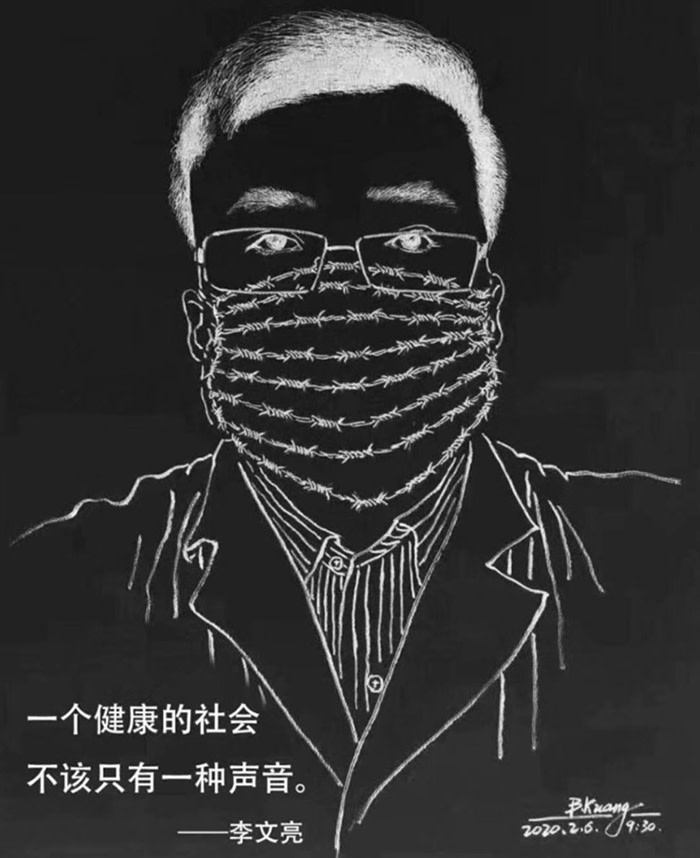

But the omissions in the document are often more telling than the official timeline itself. The Chinese Way makes no mention of Dr Li Wenliang, the national hero of the epidemic. On December 30, Li raised an early alarm when his hospital in Wuhan began seeing patients with a Sars-like strain of pneumonia.

In a chat group among physicians, he advised them to protect themselves from the virus. Days later, Li was summoned to the local Public Security Bureau and forced to sign a document admitting that he had made false statements that disturbed the public order. Many experts have argued that these early attempts to cover up the outbreak and silence Li may have prevented coronavirus from being contained to just a few Wuhan hospitals.

Also absent from the official timeline is an entry for Li’s death. He died of coronavirus on February 7: the image of his masked visage became a symbol of a government cover-up and the poorly managed response in the first weeks of the outbreak, long before the virus had spread widely elsewhere. In some drawings of Li shared online, his surgical mask has been replaced with barbed wire.

Despite the government’s initial censure of Li, after his death his image was quickly co-opted by the party as a model of selflessness and a representative of the doctors working on the frontlines in Wuhan — a motif that is still being employed.

Meanwhile, other images of Li have been scrubbed from Chinese social media, deemed too sensitive to be allowed to propagate in the country’s often unruly online circles.

Ai Fen, the head doctor at a hospital in Wuhan and one of Li’s colleagues, confirmed to a Chinese publication in March that there had indeed been a local government effort to limit public discussion of the outbreak in January.

In an interview titled “The One Who Hands Out the Whistles”, which was quickly removed from the publication’s website, Ai said: “Had I known the situation would be like it is today, I wouldn’t care if I get criticised or not, I would have told everyone.” Since then, reporters have been unable to reach her.

When it comes to controlling the public narrative over coronavirus, the stakes for the Communist party are high, says Zhou Xun, a reader in modern history at the University of Essex and a specialist on health intervention and delivery under the party.

An incident in early March — in which one of China’s vice-premiers was greeted with shouts claiming “it’s fake, it’s fake” as she toured a Wuhan residential district — highlighted the growing frustration and audacity of ordinary Chinese people who felt government efforts had fallen short.

As Zhou points out, a key element of the party’s legitimacy is derived from its ability to provide health services to its people — an idea that was undermined by photographs showing long lines of sick patients desperate for assistance. In recent weeks, the government has worked hard to guide attention away from the early missteps of the crisis, including seeking to turn the virus into a “menace from the outside”, Zhou says.

Several senior Chinese diplomats have actively promoted the idea that coronavirus may have been planted by the US military during the “Military World Games” that took place in Wuhan in October. “Such nationalistic rhetoric will also allow people to forget the earlier tragedy in Wuhan,” she says.

When it comes to China’s timeline of the crisis, Li Yuanyuan has several entries of her own to add. The temperature had dropped to 6C on the morning of February 6, when Li, an office worker in her thirties, brought her ailing 63-year-old mother to Wuhan No 4 Hospital.

Several days earlier, Zhang Shiying had been struck with a raspy cough and high fever, one of several people in her building to be overcome with such symptoms. The more she coughed, the worse it got, until she could hardly move from her bed.

A local clinic confirmed she probably had coronavirus. When the pair arrived at the hospital bundled in down jackets to protect against the cold, they joined the back of a queue that wrapped around the building.

It would be six hours before Zhang, who struggled to stand, would see a nurse and receive an intravenous injection of saline fluids often given to those who have a common cold. They made the trip on three consecutive days until her mother could no longer stand.

Following hundreds of other Wuhan residents in early February, Li took to social media as a last resort. In a short message posted on Weibo, a Twitter-like social media platform in China, she sought any help she could get, a desperate cry in cyberspace.

The message gave grisly details of her mother’s condition: “Difficulty breathing . . . constant vomiting and diarrhoea, bodily weakness, cannot eat.” Li went on to describe an exercise in hopelessness: “I’ve called the mayor’s hotline many times . . . I’ve downloaded the State Council’s app [for assistance], I’ve asked for help from community officials all without any results. So in the end I’ve had to post this here and wait.” She signed off with two namaste emojis.

“It was a terrible feeling, standing there in the cold for so long with so many people,” she tells me. “We were begging for anyone to help us. My last hope was to beg for help on Weibo.”

Assistance eventually arrived when volunteers moved Zhang to a small hotel that had been converted into a quarantine centre. She was then taken to Leishenshan Hospital, a sprawling emergency field hospital built in about 10 days to take in 1,500 patients.

All told, Zhang’s ordeal lasted from January 28, when she first became ill, to April 11, when she returned home. I speak with Li one day after her mother has arrived back safely at the flat. We talk over the phone because the household is now under lockdown, but stress and fatigue are noticeable in her voice.

She says she doesn’t know who to blame for the weeks of torment her family suffered but she knows that things were not right and that someone should be accountable for what happened.

When I ask if everyone in her building has recovered, she pauses briefly before offering a subdued response. “No, not the auntie below us. She passed away. My mum and her were friends. They were always chatting. Her symptoms were much worse early on. They went for an injection early and waited in line until midnight. Once she got into bed [back home], she did not get out. There was nowhere for her to go. The hospitals were full.”

As Wuhan awakens from the 76-day ban on travel, the streets of Hankou district are buzzing with the release of pent-up energy. There is a noticeable increase of cars on the road. On Liberation Park Avenue, a wide boulevard in central Wuhan, families have come out to bask in the early spring sunlight. For many, it is the first day in months that they have been able to walk freely on the streets.

But the damage to Wuhan is not hidden, and the fear of a second wave of disease is palpable. Many of the shops that have dared to open their doors have placed benches, tables or chairs across the threshold to keep people out. From a safe distance, customers point to the pack of cigarettes or the bowl of instant noodles they want instead of walking the aisles themselves.

The Huanan seafood market in the centre of the city, where the virus is thought to have first infected people, has been boarded up. When I visit on April 6, a large temporary wall has cordoned off the area and several police keep watch over the now-dark shops barely visible behind it.

The only evidence that the area was once a market with live animals is the almost unbearable stench that hangs over the nearby streets — a sign that, after the power in the market was shut off, proprietors had left in a hurry without cleaning out their fridges.

Elsewhere, a wartime air still lingers. Many sections of the city remain physically walled off with large blue fencing. A stroll through Hankou district reveals section after section of closed residential areas, where people are allowed to leave only to buy essential goods.

I am told by guards outside one section that an asymptomatic case of coronavirus has been found inside and the entire residential area has been shut down. Testing has become ubiquitous to root out hidden cases. One district has set up a hotline and has offered a reward for reporting people with asymptomatic cases, despite these being undetectable without a proper test.

Like many, Hao seems overjoyed to be outside and back on the streets of his city. He had his hair cut a day earlier, the first time in 100 days, he says. Several fluffy seeds falling from the sycamore trees have collected on his freshly cropped head.

Distrust has been part of Hao’s outlook since his days as a university student in Wuhan in 1989, when protests swept campuses across the country, culminating with the Tiananmen massacre that June.

Some of his anger against the Communist party runs deeper. With tears in his eyes, he tells of an impoverished childhood, when his family was forced to eat radish skins while officials lived in comfort.

Activism and revolution are also part of Wuhan’s tradition. In 1911, the city sparked off the initial unrest — now called the Wuchang Uprising — that eventually led to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, China’s last feudal dynasty.

In 1967, the Cultural Revolution came to a head in the city when students and workers clashed in deadly riots in the streets, forcing China’s leader Mao Zedong and other revolutionary elites to tone down the movement, lest they lose control over it. Hao’s father participated in the clashes, he says, and he insists that revolution and disobedience run strong in Wuhanese blood.

“When I was a child my father told me that there was a rotting body left in the streets for a month [after the clashes] — not far from here,” he says pointing toward the city’s old quarters. He tells the story with the same sense of intrigue as a child who has overheard some unspeakable detail and cannot quite grasp its significance. “The corpse swelled up to five times the normal size.”

Hao looks up and points at the camphor tree we are sitting beneath and smiles. “I like to come and sit here when it rains. The raindrops mix with the oil on the tree and it produces a lovely fragrance. The whole park smells of it.”

Surreptitiously monitoring the outbreak is a risky occupation. Hao has not posted his pictures online publicly but several of his friends actively sought to record events in an attempt to inform the public.

Among these was Fang Bin, a businessman and activist, who vanished in early February after recording and publishing a 40-minute video on YouTube in which he is heard commenting on the number of corpses accumulating at a hospital. “Why isn’t the media coming to the hospitals to report the real situation?” he asks.

Chen Qiushi, a lawyer and citizen journalist, began posting videos from around Wuhan in which he showed long lines of weak, frustrated patients waiting to see doctors. He, too, has disappeared and has yet to resurface. My attempts to locate and speak with both men while in Wuhan failed.

In what has been perhaps the most direct written attack on the Communist party during the outbreak, real-estate tycoon and high-ranking party member Ren Zhiqiang, based in Beijing, penned a missive in early February in which he accused the party of incompetence and called Xi Jinping a clown.

“When shameless and ignorant people attempt to resign themselves to the stupidity of the great leader, society becomes a mob that is hard to develop and sustain,” he wrote. His essay was shared online with a group of friends, and later circulated more widely on Chinese social media.

Ren became incommunicado in March, a close acquaintance told the FT. Some have noted that his credentials as a party insider made his criticisms an unignorable threat to the government’s narrative of a quick and transparent handling of the crisis.

On April 7, one day before Wuhan reopened to the outside world, the local party discipline watchdog announced an official investigation into the businessman.

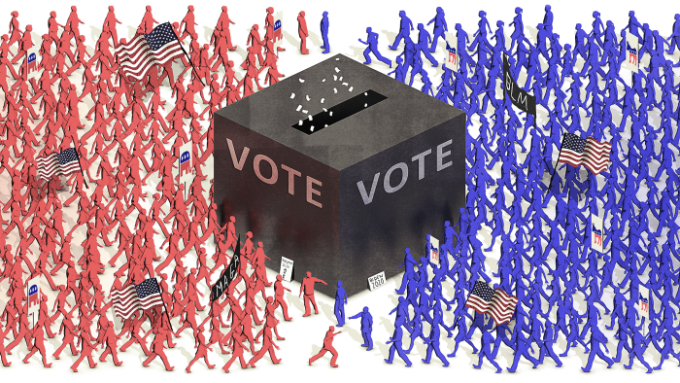

In the early days of the outbreak in China, as the Communist party came under mounting pressure over its inability to contain the spread, some experts saw a small glimmer of hope for political change in the country, says Huang Yanzhong, a senior fellow for global health at the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations. But mismanagement of the disease elsewhere in the world quickly took the onus off the party.

The announcement of the investigation into Ren on the eve of Wuhan’s reopening was a strong signal that any political change was off the table. “It was quite calculated they did that on the day before Wuhan opened up,” says Huang. “They have closed the window on any political change with the investigation into Ren.”

While the Trump administration has sought to blame China for the outbreak, the bungled US response in cities such as New York, which has more than double the number of official deaths in Wuhan, has been useful for China in deflecting criticism of its authoritarian system.

“The failure of many governments from around the world to deal with Covid-19 only goes to show that governance failure comes in many different flavours,” said Jude Blanchette, a China expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “But for the CCP, it can now point to open political systems and say, ‘See? This is what liberal democracy gets you.’”

Only when Xu Xu pulls down her mask for a sip of coffee do I realise that I have not seen her face until that moment. In fact, almost all the conversations I have had over the past week have been faceless, mask to mask. Her nose quickly disappears again and will be visible only a few more times until her cup of latte is empty.

Xu, a 28-year-old in Wuhan, was among thousands of volunteers recruited to help build the city’s biggest hospital. On December 30, rumours of an unknown virus began to proliferate on her WeChat account.

Social media is heavily censored in China and sensitive topics are often quickly scrubbed from the internet. But Xu, who has asked to use a pseudonym, and many other Wuhan locals say that knowledge of a mysterious illness was widespread enough to break through at least some level of censorship — or perhaps it had not yet grabbed the attention of government internet monitors. If her friends’ friends had heard about it, authorities must have known much sooner, Xu believes.

“This is just information shared among friends, nothing official. We really didn’t think much about it at the time and just went on like normal. We kept hearing about it but there was no real alarm for almost a month,” she says.

Looking back, she does not fully accept the narrative put forward by the government. “There are definitely questions about the early days of the outbreak . . . When they closed the city, we were terrified. I never heard the words ‘feng cheng’ before. I didn’t know that was possible.”

Feng cheng means to seal the city. On January 22, just two days after officials confirmed human-to-human transmission of the virus, the central government said it would close all transportation in and out of Wuhan at 10am the following day.

Over the next few days, the province of Hubei, where the city is located, followed suit, putting into effect a cordon sanitaire covering about 60 million people, the largest in history. In many areas with recorded cases, stepping outside one’s home became illegal. All taxi, bus and city transport was suspended.

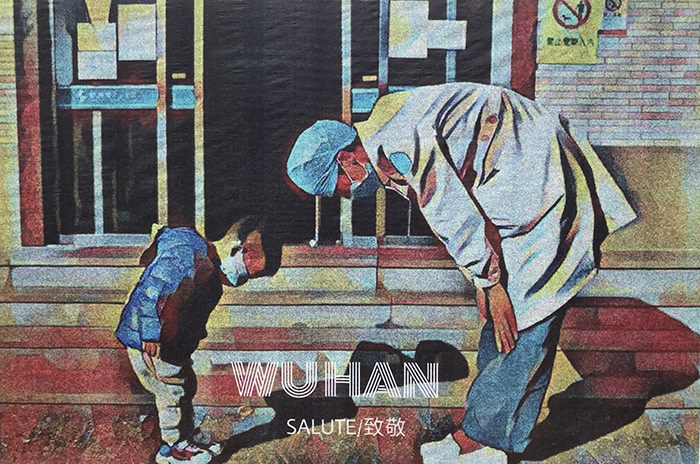

As people were forced inside and the streets emptied, Xu volunteered to head to the frontlines. She says she felt it was her duty as a young, able-bodied person to come to the assistance of the weak and dying.

On January 28, she joined a team of thousands of volunteers to build the Huoshenshan Hospital, another sprawling complex of fever wards erected in about 10 days. Xu spent that week carrying materials.

Days later she was dispatched to a neighbourhood in central Wuhan where she began delivering rations to quarantined families and also helping elderly people reach the hospital for doctors’ appointments. “We went to where no one wanted to go,” she says, referring to her many trips into areas known to have high infection rates.

Keting Field Hospital is empty by April 8, when I and other reporters are given an official tour. I never catch a glimpse of Dr Zhang Junjian’s face as he leads a group of reporters around. But above the surgical mask, his eyes show the signs of sleepless nights.

As vice-president of Wuhan’s Zhongnan hospital, over the past two months he will have seen thousands of patients, many of them deathly ill. Before it became a field hospital, Keting was a large cultural centre in the northern reaches of the city. A massive poster of South Korean pop star Rain overlooks hundreds of empty beds in the section of the auditorium we tour.

As a hospital, it treated 1,760 patients, with more than 1,400 people lying in beds in the tightly controlled fever wards at the peak of the outbreak. On one divider wall, Post-it Notes form a large heart, each with a handwritten message. It is a tribute to the patients, created by a team of doctors that came to work in the hospital from the neighbouring province of Fujian. “We are together with you Wuhan,” is written on paper cut-outs beside the memorial.

Today Keting has become a museum of sorts, dedicated to the Communist party’s narrative of success in tackling coronavirus. Standing in front of the yellow sickle and hammer on one of the many party flags pinned to the walls, Zhang tells reporters that not a single patient died there, though he admits the most serious cases were moved to a hospital next door.

Still, the field hospital stands as evidence of the party’s quick and effective work, to be shown off to visitors looking for signs of mismanagement. Steering critical questions away from the origins and early days of the outbreak, Zhang’s message is one of a return to normality in the shaken city.

Though it has not yet been added to The Chinese Way, the trip around Keting feels like we are walking to the end of China’s official timeline for the disaster in Wuhan, where the final line of the story is punctuated by an empty hospital with a flawless record.

But for people such as Hao, the outbreak has been less of a linear tale of adversity and triumph. Instead it is a reminder of the constant struggle to live outside the Communist party’s sanitised narrative.

“Some of us will disappear. This is nothing new,” he says from his seat in the park, his mask pulled down to his chin, exposing a cheerful grin. “But we will keep trying to show you what is real.”

Don Weinland is an FT Beijing correspondent. Additional reporting by Wang Xueqiao in Shanghai.

The main pictures for this article were taken by a photographer who wishes to remain anonymous

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Letter in response to this article:

The inquisition on Wuhan needs to stop / From Niccolo Caldararo, Dept of Anthropology, San Francisco State University, CA, US

Comments