Carmakers wrestle with diesel’s decline

Simply sign up to the Automobiles myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Five years ago, Toyota took an unusual decision — not to fit its newly developed C-HR model with a diesel engine.

At the time, diesel-fuelled cars accounted for half of all new vehicles sold across Europe and a higher percentage in the sport utility vehicle market.

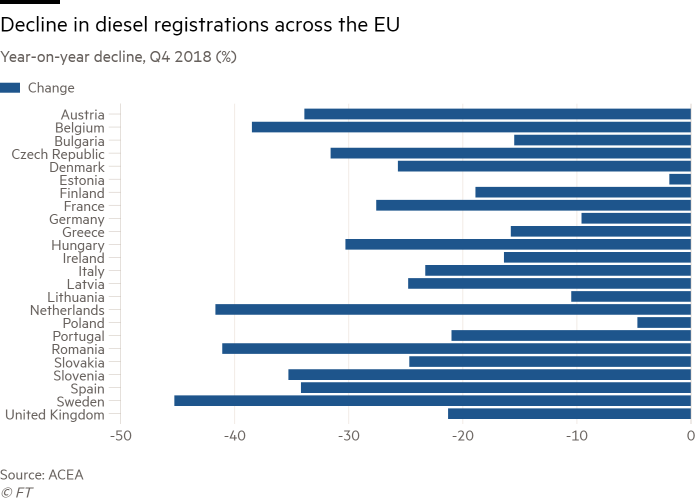

Half a decade later, that move looks prescient. Diesel sales have fallen in nearly every country, partly due to the 2015 emissions scandal, while manufacturers from Volvo to Nissan have vowed to phase out the fuel type.

Diesel’s overall share of new cars dropped to 36 per cent last year, according to Acea, the European carmakers’ association. The question facing automakers — many of which pumped billions of dollars into developing diesel technology — is how far the market has left to fall.

“The future demand of diesel will depend on how fast the electrification takes place,” predicts Felipe Munoz, automotive analyst at Jato, an auto data supplier. He argues that smaller cars, which are already seeing the sharpest fall in diesel take-up rates, will be most prone to electrification and will die out faster.

“But as the electrification of SUVs [sport utility vehicles] has proven to be more complicated, and diesel is still the main choice among some its subsegments, so they might still have significant demand in the coming years.”

Diesel’s decline has not been equally felt. In Belgium, diesel’s share of new sales has fallen from 60 per cent in 2015 to just 36 per cent last year, according to figures from Jato. But Germany, where diesel-making car producers are near synonymous with the country’s economy, has seen a more modest slip in diesel share of new sales from 48 per cent to 33 per cent.

It has also fallen unevenly across segments of the market. While the number of small diesel cars registered in Europe fell from 825,591 in 2015 to 468,856 in 2018, registrations of SUVs rose from 2.1m to 2.4m.

The rate of overall decline appears to be slowing across the region, suggesting the customer backlash is softening. But any further intervention from politicians — for example, city mayors who have clean air to consider but no industrial base to defend — could drive sales lower still.

“While the decline seems to be levelling out, legislation across Europe to limit its [diesel’s] use in cities is the next big thing,” says Tim Lawrence, head of manufacturing at PA Consulting. “The focus of regulation is on older diesel for now, but full diesel bans will come in over time.”

London is one example, where a hefty charge for driving older diesels in the city centre will be broadened to include a far wider area from 2021.

For carmakers, this threat to the fuel type hits more than just their past investment. For many, it upends their key strategy to hit tough Europe-wide targets for reducing CO2 emissions, which come into force from next year.

Diesel was a key pillar for companies such as BMW and Jaguar Land Rover, mainly because it emits a fifth less CO2 than petrol equivalents.

Carmakers face an “uncomfortable juggling act”, says Mr Lawrence, as they try to reduce their emissions and fines by persuading consumers that diesel is better than petrol when it comes to CO2.

Fiat Chrysler, which has one of the highest diesel mixes in Europe because of the Jeep brand, has already said it will roll back an earlier pledge to phase out diesel.

“Some segments are moving slightly differently than we thought, some are much more resilient, some less so, so let’s make sure we have the flexibility,” chief executive Mike Manley told the Financial Times earlier this year.

The company has also struck a deal with upstart rival Tesla to pay hundreds of millions of euros for European regulators to treat their vehicles as a single fleet — allowing Tesla’s electric vehicles to offset FCA’s more heavily polluting vehicles.

If consumers are ditching diesel, they are broadly switching to petrol rather than electric — pushing up CO2 rather than spurring the clean car revolution that had been hoped. The reason for this, say market insiders, is that electric cars are still not ready for mass take-up.

A wave of new electric vehicles will be launched in the coming 18 months, in part so carmakers can hit the CO2 targets. But consumer caution over them lingers, stemming from concerns such as price and how far they can drive before requiring recharging.

“There’s actually not a lot of choice, and most of the electric vehicles that have been out there in the last five to 10 years have been quite expensive,” Bentley’s chief executive Adrian Hallmark told the FT’s Future of the Car Summit last month.

Mr Hallmark added that advances in battery technology are needed for electric vehicles to have extensive range. “If you try to build a big SUV as a full battery electric vehicle, or a Mulsanne [a Bentley model], it would go really well . . . for a very short distance.”

Comments