Sweden’s strict controls drive ‘booze-cruise’ economy

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Every Friday evening at 7pm, Johan Segerberg dons a tuxedo and a bow tie, climbs into his van and crosses the Oresund Bridge from Malmö in southern Sweden to Copenhagen.

Laden with cheap booze, he returns to customers eager to beat the strict opening hours of Systembolaget, the government-run alcohol monopoly store.

After 7pm on Fridays, and 3pm on Saturdays, there is nowhere in Sweden to buy a bottle of wine for home consumption, let alone anything stronger. “What we are selling is the convenience of getting alcohol delivered when you want it,” Mr Segerberg says. “We need to debate whether the current way of alcohol control via monopoly is the only and the best way we have of doing it.”

Mr Segerberg’s unusual take on a man-with-a-van is just one example of how Sweden’s 62-year-old alcohol monopoly is feeling its age, with signs of tension between the aims of Stockholm’s social engineers and the daily habits of modern Swedes.

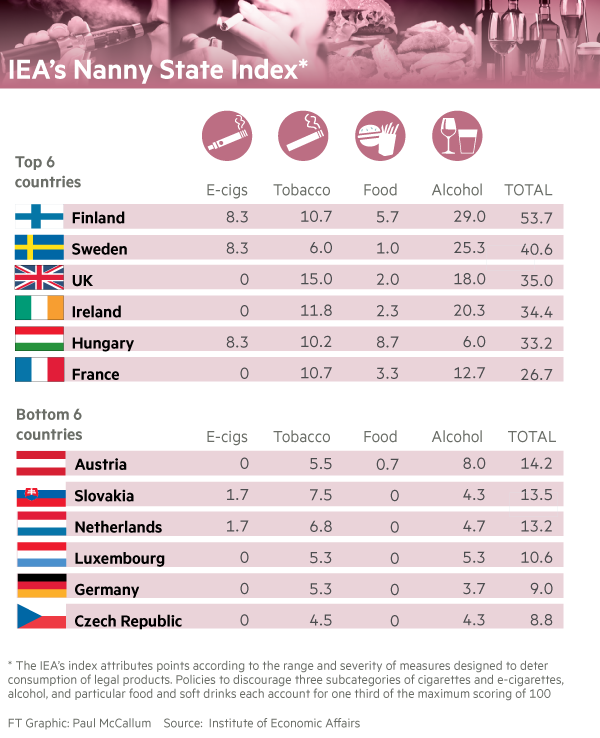

Long seen as a country with a passion for intrusive social legislation, Sweden’s alcohol policies may seem like an anachronism. Yet the monopoly, and a tangible official puritanism that accompanies it, appear to be thriving.

Ready alternatives to Systembolaget, where basic wines are typically priced around SKr100 (€10.60) and bottles of beer at SKr25, lie across the water. Daily ferries to Denmark, Germany and the Baltic States cater to hundreds of thousands of alcohol shoppers a year.

About one-fifth of the total alcohol consumed in Sweden — and half the spirits — arrives via this route, according to the Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, or CAN. The largest ferry operator, Stena, sells some 250,000 day tickets to Denmark each year from Gothenburg. Most travellers never leave the terminal on the Danish side, returning with trolleys piled high with drink.

While there is no limit on the quantity of alcohol that Swedes can bring into the country for personal use, there is an illegal smuggling trade amounting to 5 per cent of total sales, says CAN. Dozens of buses load up in Germany each week with alcohol for resale.

“Sweden’s alcohol policy has produced mixed results and unintended consequences from both economic and public health points of view,” says Jan de Grave for Brewers of Europe, a Brussels-based lobby for Europe’s brewing industry. “Those who are inconvenienced are rather the moderate drinkers while the determined alcohol drinker will always find a way,” he says.

The monopoly is under pressure, according to Håkan Leifman, director of CAN, who also sits on the board of Systembolaget. But this is not new, he says — the pressure was far greater when Sweden joined the EU in 1995 and was forced to increase the amount of alcohol that Swedes could bring in from abroad.

“We were very concerned when Sweden joined the EU that we were joining some of the most liberal alcohol cultures in the world,” Mr Leifman says. “Sweden’s alcohol policy is more liberal than 25 years ago, and consumption is 20-25 per cent higher than before we joined the EU. But we have still managed to keep rather high prices and restricted availability.”

More porous borders and the liberalising influence of EU accession have weakened the effectiveness of long-established state strictures meant to curb alcohol supply. But lifestyle trends and public opinion continue to bolster Sweden’s idiosyncratic approach to tackling the social ills of excessive consumption.

Mr Leifman notes there has been a “dramatic” decline in the amount of alcohol consumed by young people. Moreover, hostility towards the monopoly among Swedes has fallen steadily since the turn of the millennium, down from more than half to 30 per cent in 2014, according to Gothenburg’s SOM Institute for public opinion research. Just 17 per cent favour lower taxes on alcohol, down from almost 60 per cent in 2005.

Among the political parties, only a few ideological liberals are prepared to criticise the monopoly. “I believe Swedes are mature enough to handle the same alcohol policy that Germany and France have,’ says Maria Weimer, an MP for the opposition Liberal party. “We do have a responsibility to try to help those who can’t handle alcohol, but that could be done in other ways.”

The Sweden Democrats, Sweden’s populist, anti-red-tape rightwingers, argue that “farm sales” of alcohol should be permitted as a boost to small businesses, but even they do not want to see Systembolaget abolished.

Research consistently suggests that privatisation of retail sales would see consumption increase by about 30 per cent and alcohol-related harm rise by a similar amount, according to Sven Andréasson, professor of social medicine at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute and one of the country’s foremost alcohol researchers.

“The monopoly reduces — not dramatically but importantly — the consumption levels of alcohol, it is an intelligent way of dealing with an acknowledged problem without seriously impacting on availability for those who want it,” Prof Andréasson says.

Yet Systembolaget is an anachronism in a modern Sweden in which state-run monopolies on everything from pharmacies to the railways have long been abolished. “It is a mystery why Swedes are so fond of the alcohol monopoly,” Prof Andréasson says. “It doesn’t help clarify anything to say that it’s about history and culture, because we share so much with other European countries.”

On the ferry from Denmark to Gothenburg, surrounded by Swedes laden with crates of cheap drink, medical student Ida Eriksson fears a more liberal alcohol regime could lead to problems such as diabetes and obesity.

While alcohol consumption per head in Sweden lags behind Denmark, alcohol dependency still exceeds the European average, according to WHO data.

“The inconvenient opening hours at our alcohol stores are worth the long-term health benefits. I love Systembolaget!” says Ms Eriksson.

Additional reporting by Nicholas Thomas and Josh Worth in Gothenburg

Comments