The art of portraying power, wealth and entitlement

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There is a silent game taught in acting school using eye contact, body language and a deck of playing cards. Each person in the group picks a card and has it stuck to their forehead without knowing whether they are the ace (the most powerful), the two (the least powerful) or any card in between. The cards denote status, and you must walk around the room giving the most status to the player with the ace, then to the king, then to the queen and so on down through the numbers.

At the end of the game, everyone has to guess their own ranking. The players with numbers in the middle of the deck often feel confused: they get a lot of mixed signals about where they are in the hierarchy. But every actor knows what happens if you draw the ace. You don’t need to do anything. Because everyone simply defers to you.

The projection of extreme status, power, wealth, entitlement — or even simply self-assurance — is an art. Its most recent and perhaps highest expression was achieved in the TV show Succession, which charted the waxing and waning status of four siblings — and a host of other wannabes — all chasing that elusive, singular ace in the pack. That kind of status projection is also in evidence in Ozark, House of Cards, The West Wing, The Crown or any compelling screen performance where someone has to carry themselves as entitled or powerful.

In real life, this station can be rare and rarefied. So it’s not surprising that it involves intense and intentional preparation to fake it without looking like you’re faking it. Playing Gerri Kellmann in Succession, a role which required “interim CEO energy”, J Smith Cameron called this feat “lowering your internal temperature.” Sarah Snook, Shiv Roy in Succession, has talked about using silence as her weapon. Born in Adelaide, Australia, Snook wasn’t certain in the early stages of the process that she had nailed Shiv’s American accent so she kept her counsel and played “enigmatic”: it ended up being a genius status-raising move for the character.

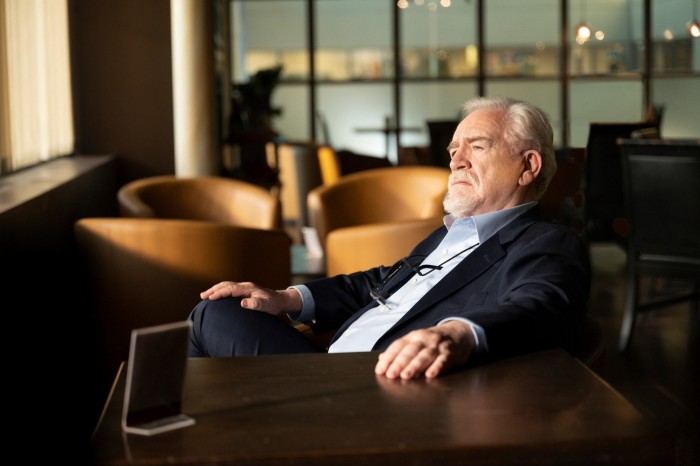

For some, these acts are cautious, planned, rehearsed. For others, they are instinctive and almost unconscious. I interviewed Brian Cox (the patriarch, Logan Roy in Succession) for the podcast How to Own the Room alongside his wife, actor/producer Nicole Ansari-Cox (who played a cameo as one of Logan’s mistresses in the penultimate episode of Succession). He expressed discomfort with the idea of “owning” a space: “I find it a bit of a difficult concept. It sounds a bit proprietorial to me.” Ansari-Cox laughed: “You do it all the time though.” He laughed back: “OK . . . I do it unthinkingly . . . I own the room unthinkingly . . . I suppose owning the room is being centred in whatever environment you’re in and not feeling proprietorial, feeling like . . . you’re there and you contribute.”

This echoes a common maxim about status in the acting world: status can only be conferred on you by others, you cannot take it. Your job is just to be there, to be the ace. While the markers of supreme success may seem mysterious and unattainable to us in real life — and we wouldn’t dream of “behaving like a CEO” unless we actually were a CEO — actors are required to take on the mantle of wealth, power and status effortlessly and without us being able to see the performance. How do they do that? And what can we learn from their craft that might benefit us in our own lives?

It’s obvious that a believable portrayal of status is not achieved simply through details of costume or environment. Of course, coded luxury was signalled in Succession by Kendall Roy’s $605 cashmere Loro Piana “stealth wealth” baseball cap and Shiv’s $2,000 Armani trouser suits. But this is a world away from the 1980s portrayal of ostentatious wealth in the soap opera Dynasty, when, in one famous scene between Alexis Carrington (Joan Collins) and Dominique Deveraux (Diahann Carroll), the two discuss Dominique’s explicitly stated preference for beluga caviar over the less expensive oscietra. Instead of this obvious signalling, our contemporary understanding of power often comes through behaviour and the unspoken responses of others, especially as many overt status symbols are now seen as crass.

The thing about status is that most of us just don’t have it, says Josie Rourke, the former artistic director of London’s Donmar Warehouse. Rourke directed the Oscar-nominated historical drama, Mary Queen of Scots, starring Saoirse Ronan and Margot Robbie. She puts it bluntly: “It’s really hard to avoid being ‘Greg’ in real life.” Greg Hirsch (Nicholas Braun) is the character in Succession with the most common everyday status: a great-nephew with little claim to the throne, he is put-upon, belittled, taken advantage of. He craves status, but is not able to achieve it. “A lot of the reason people loved Greg in Succession is that, among all these venal characters, he elicits sympathy. You feel for him being shouldered out or ignored. When he approaches high status figures — for example, in the scene after the funeral where everyone was approaching the president — the body language conveys people trying to ice him out and pretend he isn’t there.” We sympathise (and cringe), because we’ve been there.

Actor Paul Chahidi has played many versions of status and power over his career on stage and screen, including politburo member Nikolai Bulganin in The Death of Stalin. But, even when high-status characters are being played for comedy, they still have to look as if they belong in the world they inhabit. “There is a commonality between who has status and who is at ease in the room,” he says. “People with status are simply being themselves — they are not transforming themselves. They let others come to them. It’s like an unseen language. When you are at ease with yourself, it’s the most powerful thing.” Again, he adds, this must feel real: it cannot be a pretence. One technique to increase status and enhance this feeling, he says, is to “take your own sweet time in taking a beat or in answering a question. For example, you can hear this on the radio, on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. You get interviewees who, when they pause, are genuine in taking a moment to consider the question. It must be genuine. When you hear it, it’s electrifying, because it’s real.”

We cannot always articulate exactly why someone is powerful, but we can feel it — and we can hear it in their voice, which may be sparingly used. Samara Bay is a dialect coach on Hollywood movies and author of Permission to Speak: How to Change What Power Sounds Like, Starting With You. She has worked on set with actors such as Pierce Brosnan, Rachel McAdams, Penélope Cruz and Gal Gadot. “The person who is worrying the least about being taken seriously . . . that is the person with the most status. You are most yourself when you are expending the least effort. That is what is powerful.” In real life — as on screen — this is about banishing self-consciousness and finding that feeling of ease and belonging, regardless of your station in life.

This is obviously manifested in the portrayal of someone wealthy, as their station in life is assured. “Money is a stand-in — money itself doesn’t matter,” Bay continues. “What matters is our relationship to it and what it says about who we are. We all know rich people who are unhappy and we all know people who are not rich who have found inner peace. Finances certainly help with comfort in life and with status. But peace of mind is real status. As we can see in Succession, having great riches only opens up new challenges.”

This is why the status of many of the characters in Succession is often surprisingly low: their world does not really give them comfort or peace because they don’t actually crave wealth (which they already have), they crave power. Arguably, Connor Roy (played by Alan Ruck) — Logan Roy’s eldest son by his first marriage and the one least interested in the family business — is the Roy sibling with the most comfortable status. He spends millions of dollars running to be president but doesn’t seem especially bruised to lose. Ruck has said: “Connor’s not dumb, but he’s marching to a beat that no one else can hear.” This is the ease and lack of self-consciousness Bay is talking about, even, if in Connor, it borders on the delusional.

The Canadian actor Kerry Shale jokes that he has moved upwards in status during his career, going from “low-status parts (officious clipboard carriers in short-sleeved shirts and bad ties) to high-status arseholes in nice suits (mayors, government officials)”. As an actor, you often have to tailor your character’s status according to that of your scene partner: Shale has played the US secretary of state to Morgan Freeman’s president in the movie, Angel Has Fallen, and an actor’s agent, opposite Steve Coogan in TV’s The Trip.

In the portrayal of wealth, in particular, the impression for the audience must be immediate, he says, especially if your character is a minor one: “One of the smallest parts I had to play where I had to establish status immediately was when I played ‘the Texan’ in a movie where there is a jewel robbery and he ends up getting knocked out. He had maybe two lines in a Texan accent. I just asked for a huge cowboy hat. Because only a really rich person would have the nerve to wear something as outrageous as that.”

Sometimes, entitled status is signalled internally and not using props. Shale recently played the mayor of Gotham City in the unreleased Batgirl movie: “He was essentially a humourless sociopath. So I just thought about Donald Trump . . . in my head, I was Donald Trump. Although I didn’t tell anybody that. When I smiled, I didn’t look like me . . . I looked like Donald Trump filtered through my face. A dead-eyed, humourless smile. I felt incredibly powerful, like nobody could touch me. They were all little humans.

“They were all so far beneath me, it was ridiculous. ‘Look at all the little humans!’ A crazy person is the highest status person you can be. I mean, when you think about Donald Trump . . . he walked in front of the Queen.” For Shale, it suggested she didn’t exist for him. “If I had trouble getting into character — because we had night shoots at 4am in Glasgow — I would just smile and think of Trump. That horrible not-smile.”

But it is not so easy transferring the trappings of status, entitlement and wealth to our everyday lives. As Shale puts it, “When you go into Starbucks, channelling Donald Trump is not going to get you anywhere. It’s just going to get you bad service.”

Theatre and film director Rourke says that techniques for making you seem to have more status than you do in real life can make her feel anxious: “People say things like ‘slow down’, or ‘exhale more often’, or ‘go quiet’. They may be effective at maintaining status, but they can be at odds with maintaining a sense of self. When I started my career, a male director told me that I ‘spoke too quickly’ to be a theatre director, and it made me neurotic for months.”

Instead, she learnt to trust her own communication style and just be herself. Now, her only advice on status for real life is this: “If you’re feeling under pressure, stop worrying about yourself and start watching the other people.”

Generally, being less self-conscious whilst being as close to your natural self as possible is the highest form of status. “If you try and hide and suppress who you are, you end up being inauthentic and that just lowers your status,” says the actor Chahidi. “Admit insecurities, but be articulate and have ideas. That can be an impressive alchemy.”

Maybe that’s why Gerri is one of the winners on Succession. J Smith Cameron: “She can play poker. But the audience can see she’s twitching, she’s a nervous wreck.” True wealth? Showing others you’re mighty, but also only human.

Viv Groskop is the author of ‘Happy High Status: How to Be Effortlessly Confident’

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments