Bank Australia sees climate action as key to customer growth

Simply sign up to the Asia-Pacific companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

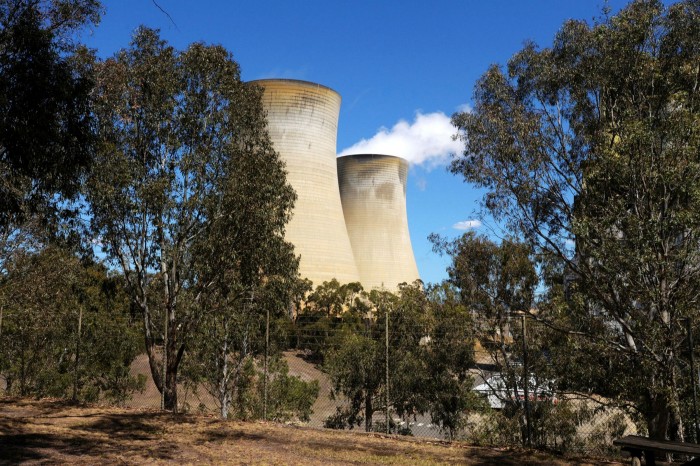

Moe, located in the Latrobe Valley in the Australian state of Victoria, has a long association with fossil fuels. The region is rich in brown coal, and Moe is home not just to the miners who extract it but also to the State Electricity Commission workers who burn it at the nearby power plants.

The resulting greenhouse gas emissions mean the region is a big contributor to Australia’s overall carbon footprint — and it is accordingly bracing for the country’s energy transition. Power stations such as AGL’s giant Loy Yang plant, to the east of Moe, look to be on borrowed time as the country plots a path to net zero by 2050. Even the future of AGL itself — and Australia’s other big energy providers — may be defined by those who want a faster transition.

And one of these emission evangelists is another key player in Moe’s economy: Bank Australia, which has its customer service operation in the town. It is one of the largest non-power employers there, and has set an ambitious target of achieving net zero emissions by 2035, including across its lending portfolio. Bank Australia is making progress, too. Of the businesses on the FT’s new Asia-Pacific Climate Leaders list — compiled with Nikkei Asia and data provider Statista — it has cut its Scope 1 and 2 emissions relative to revenue the most. Scope 1 and 2 emissions arise respectively from a business’s own operations and from the energy that it purchases.

Damien Walsh, Bank Australia’s managing director, says that having staff and customers in the Latrobe area has helped strengthen its decision to push hard in driving the country towards net zero.

“Part of our role is to support the transition from the coal-fired energy economy,” he says. “We are growing in that region by attracting customers who want to be part of that change.”

The bank traces its roots to the mid-1950s when it was founded as a co-operative credit union for the government’s scientific research department. It went on to absorb more than 70 similar organisations — including the SEC’s credit union — before becoming a bank in 2011 and rebranding as Bank Australia in 2015.

Walsh says it adopted its climate stance in response to its customers, each of whom — since the bank has retained its co-operative ethos — has voting rights at the annual general meeting. They made it clear that climate change was a top priority by “leaps and bounds”, Walsh says.

Bank Australia moved to be carbon neutral by 2011, a goal it achieved after it bought a conservation reserve in west Victoria. This helped the bank offset the environmental impact of the new buildings it financed. Eight years later, it moved all of its own energy supplies to renewable sources.

The approach has paid off in terms of attracting customers: it currently has 183,000, with the growth rate doubling since the bank launched a “clean money” investment framework in 2019, according to chief impact officer Sasha Courville. The initiative directs investment away from fossil fuels, live animal transportation and weapons, and towards areas such as renewable energy.

Transitioning from fossil fuels has become a live issue across Australia, which remains one of the largest coal and gas exporters in the world and has suffered a series of climate-related disasters, including bushfires and floods. Climate activists have been quick to criticise the country’s “Big Four” banks — ANZ, Commonwealth Bank, NAB and Westpac — for continuing to fund fossil fuel projects (they make it on to the Climate Leaders list as so-called “financed emissions” fall outside Scopes 1 and 2.)

The strength of feeling was demonstrated last month at a banking summit in Sydney, organised by business newspaper the Australian Financial Review. A 15-year-old schoolboy, driven to protest after witnessing a cyclone that swept through Western Australia last year, confronted the Commonwealth and NAB chief executives and demanded that they stop financing the fossil fuel industry.

More stories from this report

The chief executives defended their record, with Commonwealth’s Matt Comyn arguing that the bank’s policies were aligned with the Paris Agreement on climate change and fossil fuels accounted for just 2 per cent of the bank’s balance sheet.

But, while banks might try to frame the funding of fossil fuels as only a small part of their business, Dan Gocher, director of climate and environment at the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, a shareholder advocacy organisation, says: “They come out with plenty of statements about net zero but it doesn’t have an immediate impact or stop the big expansion of fossil fuel projects.”

Gocher adds that most of the larger banks remain “passive” in their approach to climate change. “It’s business as usual for the banks who are not taking the hard decisions.”

The banks do, however, have support from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, the country’s financial regulator. It argues that it is important that Australia’s financial institutions support fossil fuel companies that are transitioning from “brown” to “green” energy sources.

For its part, Bank Australia argues that hitting net zero goes beyond “clean money” financing and to the heart of its mortgage book, which represents 84 per cent of its lending.

“Customer [property] ownership represents the vast majority of (our) emissions,” Courville says. The bank says 23 per cent of Australia’s emissions are from buildings, with half of that from homes. So it offers discounted loans to people buying homes with solar panels, double-glazing or insulation — arguing that lending policies can help make residential energy use more efficient.

Gocher adds that some larger banks have launched products for solar power and electric vehicle purchases, which have proved successful but are “piecemeal” without government support. He notes that last month’s change in government — with new prime minister Anthony Albanese promising a 43 per cent cut in emissions from 2005 levels by 2030 — could help push such initiatives further.

Walsh says Bank Australia can risk driving the shift toward net zero because of its small size, but that the whole sector needs to move faster. “We can’t do this on our own,” he says.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments