Game, set, matched – when David Shrigley met Andy Murray

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

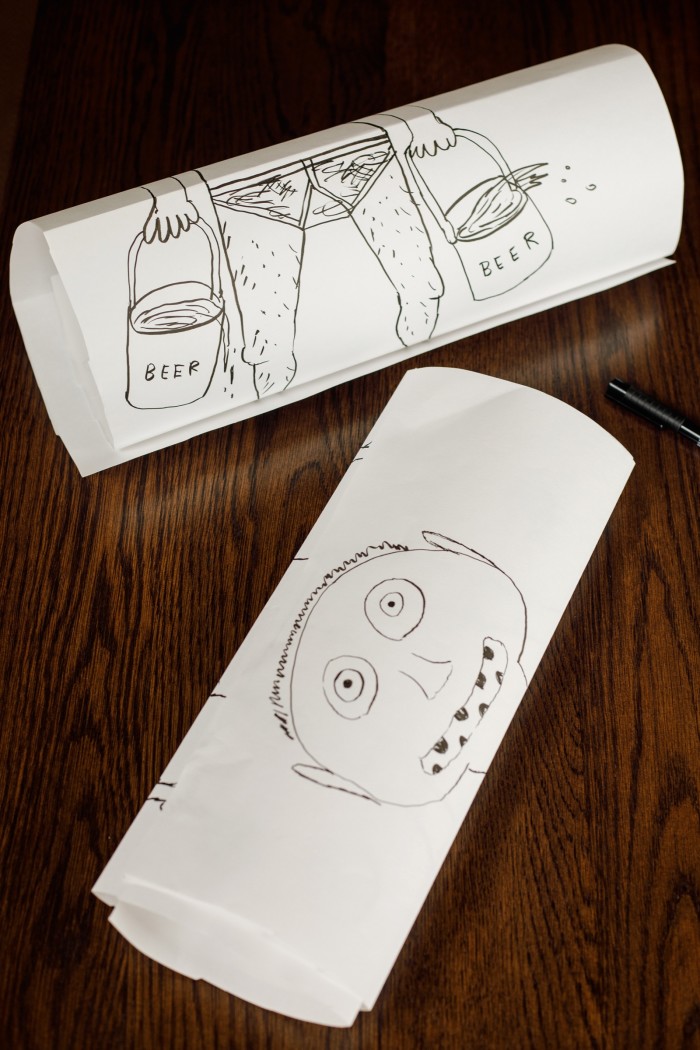

“We are making an exquisite corpse,” the artist David Shrigley tells a bemused Andy Murray. The cadavre exquis, he explains, was “popularised by a group of French surrealists, including André Breton, nearly a century ago”. But the explanation doesn’t help.

To the rules, then: a piece of paper is folded over into four sections where each participant takes turns to draw body parts, from head to feet. The game is new to the two-time Wimbledon champion, whose youth was dominated less by drawing than competitive tennis from age five.

The artist and tennis legend share a Scottish connection: Macclesfield-born Shrigley lived in Glasgow for 27 years after attending the city’s revered School of Art. Murray was brought up three miles away from here in Dunblane. They are mutual fans, which is evident on the walls of Cromlix, Murray’s hotel, that are adorned with Shrigley’s work. They have come together today to walk, talk and doodle.

Murray is an unlikely laird of the manor. His decision to buy the 15-bedroom property, set in the bucolic Stirlingshire countryside, was driven by sentiment: “I wanted to save it from falling into the hands of an oligarch who would never use it,” he says. “Despite everyone advising me against it.”

Cromlix has long been a part of the tennis player’s family history. The first event held at the hotel after its conversion from a private residence was the silver-wedding anniversary of Roy and Shirley Erskine (Murray’s grandparents) in 1981. They still live nearby, as does his mother, Judy. Many other celebrations followed over the years, including the Erskines’ 50th anniversary and Murray’s wedding reception after his marriage to his wife Kim. Older brother Jamie was married in the on-site chapel, which dates back to 1874.

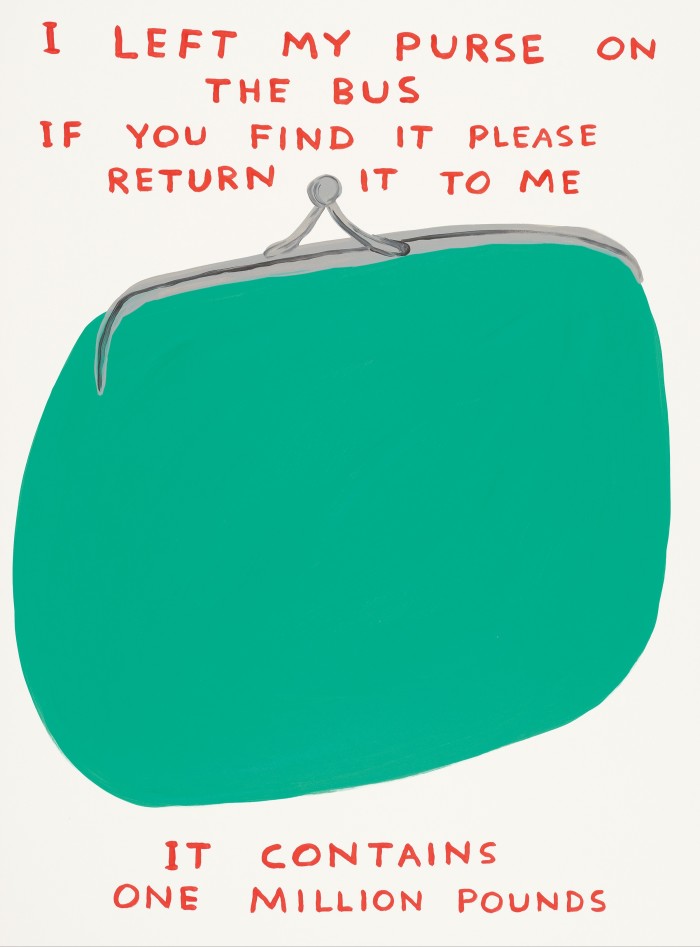

Kim managed the five-star hotel’s recent refurbishment, which now reflects the couple’s own tastes and preferences. There is art everywhere, including pieces on loan from the Royal Scottish Academy and from the Murrays’ personal collection. Indeed, Cromlix has afforded Murray the opportunity to experiment with curation, supporting new and established talent. He likes pieces that not only bring him great pleasure, but also offer visitors an accessible entrée to contemporary art. Hence the prominent placing of a quartet of Shrigley’s colourful animal screen prints in the entrance hall.

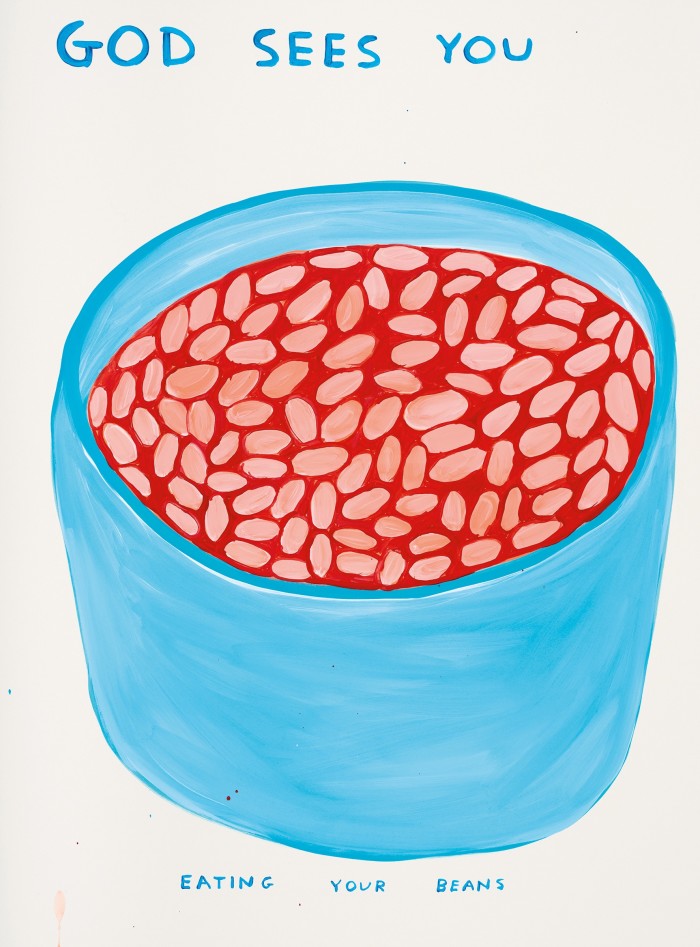

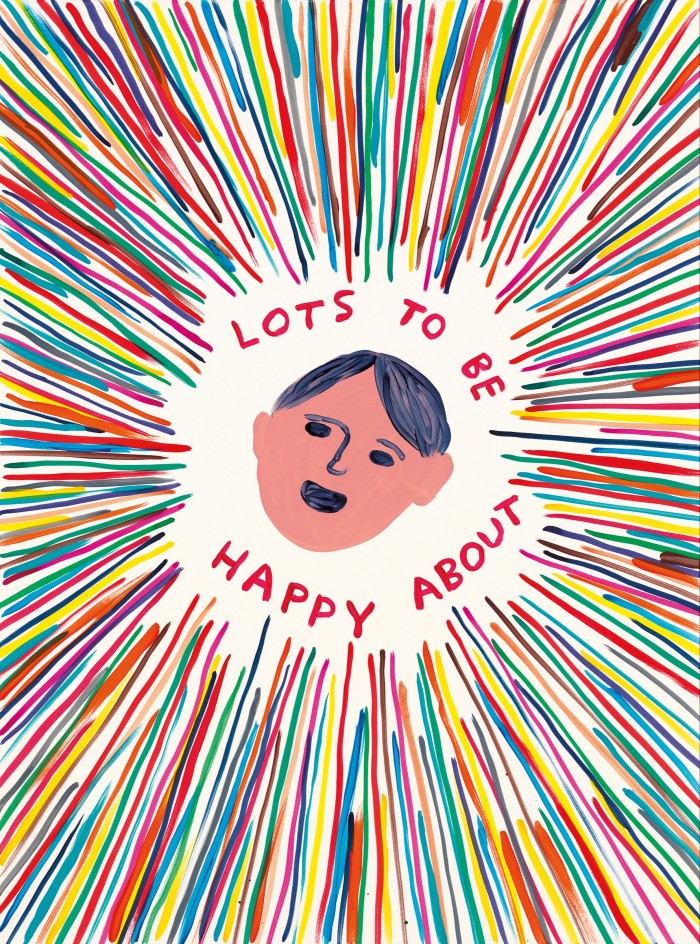

“It’s funny because you never know where these pieces go,” says Shrigley gazing at his artworks. “I forget what I’ve done because I make a lot of work on paper.” Shrigley is known for a simple, cartoonish style with hand-rendered text, realised in drawings, paintings, sculptures and installations that comment on the everyday, from personal observations to political statements.

Shrigley works with Jealous Gallery in London, and finds the screen-making process “amazing”. “They do two screens for the sheen of the paint, replicating the brushstrokes and acrylic paint. It’s mind-boggling, and so good that quite often the only way I can distinguish between the original and a print is by touch,” he admits.

Murray began collecting Shrigley’s work after seeing the image of a small black dog (the artist’s beloved schnauzer, Inka) with a red ball, captioned, “His relationship with the ball is more complicated than it first appears.” Murray bought the piece: “It’s placed just outside our bedroom at the top of the staircase. We have a terrier and the way he carries on with tennis balls is mental.”

It was Inka that first inspired Shrigley’s 2021 project Mayfair Tennis Ball Exchange at Mayfair’s Stephen Friedman Gallery, for which he displayed 12,166 pristine tennis balls equal distances apart on purpose-built shelving. “It was like a dadaist shop where you were invited to exchange something that, to all intents and purposes, was exactly the same as the thing you were swapping it for,” recalls Shrigley. “I’d envisaged people would bring a skanky ball, covered in dog spit and dirt, and exchange it for a nice new one, changing the exhibit very subtly over time. What actually happened is that people made art on their tennis balls and so it became a weird art exhibition. What one has to realise about the public is that you cannot predict what they will do. But if you are genuinely engaged with them, you have to accept the outcome.”

The next iteration of the Tennis Ball Exchange will be installed at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, in January 2024, to coincide with the Australian Open. Murray hopes to be amongst the patrons. “It’s one of my favourite tournaments and I adore Melbourne,” he smiles.

It’s the playful aspect of Shrigley’s work that first attracted Murray to his art – though not before he had made a botched attempt of his own. “A tennis-coach friend had been trying to get me interested in art for a while. He showed me some paintings he liked, and I said, ‘Mate, I could do that!’” he recalls. “One evening, I decided to create my own art and, needless to say, it was a disaster. I was trying to flick paint at a canvas like Jackson Pollock, and most of it ended up on the walls and the ceiling. I realised it was much harder and nuanced than it looked, so I decided to educate myself a bit more before making such dismissive comments.”

Armed with newfound appreciation and knowledge, Murray made his first acquisition at the 2018 Sotheby’s auction of the collection of Frank Dunphy, Damien Hirst’s former business manager. His tastes are contemporary, ranging from Banksy – whose excellent exhibition Cut & Run at Glasgow’s GoMA was on his list to see en route home to Surrey after this visit – to the expressive stylings of Maggi Hambling, for whom he has sat before.

As the two relax in the bright drawing room at Cromlix, there’s an easy camaraderie between them. Murray has just returned from holiday in Portugal following his “gutting” second-round loss at Wimbledon. He wonders “how long I can keep putting in the work for, if I’m not getting the results?” But still he keeps playing “because I love it and I’m finding it difficult to replace what tennis gives me”. He turns to Shrigley and asks about his typical working day. “I do eight hours, five days a week. I go in at 10am, make drawings and take the dog for a walk,” Shrigley answers.

Murray wants to know more about the evolution of the artist’s style, which Shrigley thinks is more “like an absence of style”. Looking back on his early career, he reflects that “the drawings were diaristic and to make people laugh. At some point, I became that guy, doing that thing.”

It’s time for the two to put pen to paper and draw their exquisite corpse parts. Shrigley commands his pen with sweeping flourishes across the page. Murray cringes and giggles his way through the session. “I’ve got a terrible imagination and I can’t draw,” he says. Finishing up, he laughs at his struggle with scale: “I’ve drawn a tennis racket, which is half the size of the ball it’s right next to.” It’s time for the reveal. There is little doubt as to who created which section, as they each sign a copy.

Back on safer ground, they muse on the joy of collecting. When asked what they’d love to acquire, Shrigley calls out: “Philip Guston, but it would be hard justifying spending a million pounds to my wife.” Murray retorts: “I did ask if I could have a racket from Roger Federer’s last match. Apart from that, I’ve never collected anything but art.” He got the Federer racket, and it’s something he holds dear. “I love that I have that memory from the last match of his career.”

cromlix.com. David Shrigley’s latest project, Pulped Fiction, will be launched on 26 October; his book “I Am the Jug, You Are the Glass” (€35) is available at davidshrigley.com

Comments