Cillian Murphy is enjoying the moment

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The first time I met Cillian Murphy was at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, in 1997. The actor, then 21, was making his stage debut in Disco Pigs, a two-hander about teenagers from Cork, Ireland, a frenetic story about friendship and first love.

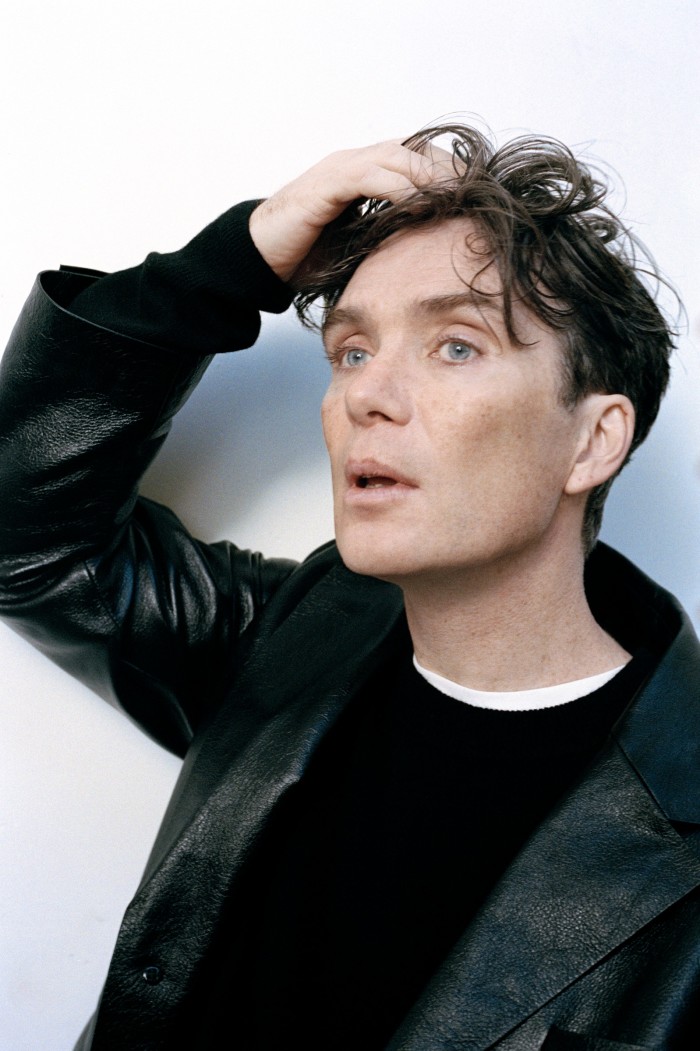

Even then, in tight-fitting silver trousers that looked like tin foil, fearless, feral, Murphy had a magnetism that ricocheted around the room. That ethereal face, that deep, laconic Irish accent, those ice-blue eyes held everybody in his thrall. He would wind down after each performance with several pints (and an odd obsession with Chumbawamba) with the company, a wild gang who were all great friends. Had you asked me then if he might one day win an Oscar, I would have nodded: absolutely, yes.

Last month Murphy picked up his first Academy Award for best actor for Oppenheimer, crowning a 28-year career. Thanks to Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later, six films, including Batman, with the filmmaker Christopher Nolan, and Peaky Blinders, Murphy is established as one of the best-known actors of the modern age. He has also continued to pursue new roles in theatre, working regularly with the same creative team. Enda Walsh, who wrote Disco Pigs, is now my husband, and he and Murphy still collaborate every few years. As such, I’ve long had a ringside seat to his successes and know his wife Yvonne McGuinness, an artist, and their children Malachy (18) and Aran (16), who now live in Dublin. A testament to his universally attractive features: as a toddler, my daughter would call him “Kiki” and try to stroke his face.

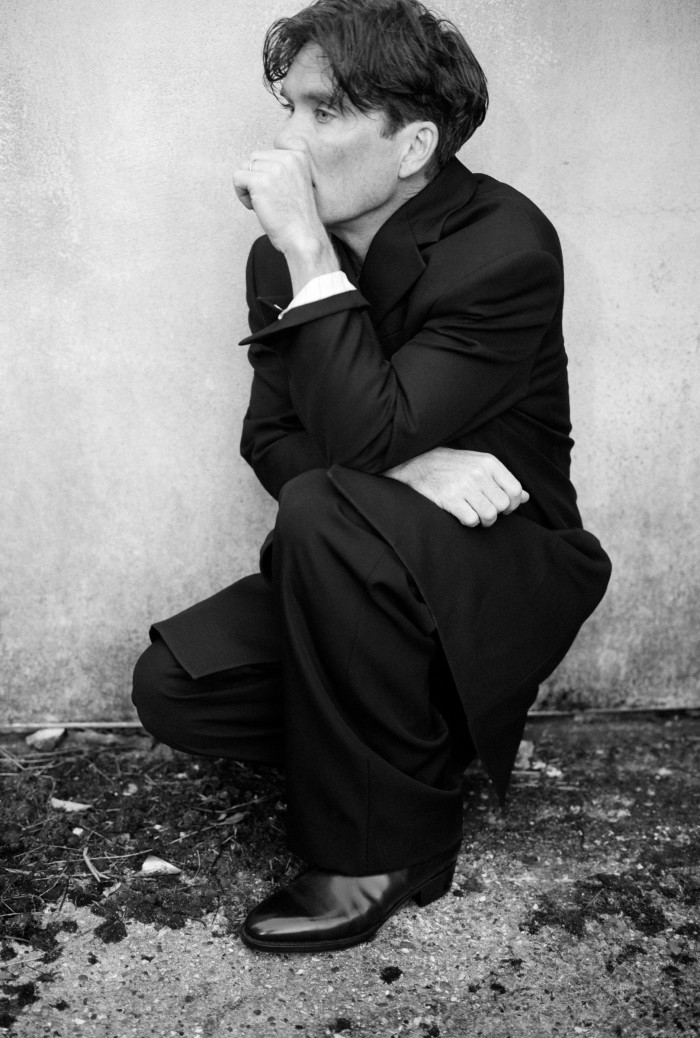

Our first meeting for this profile took place on the HTSI shoot at Wapping Power Station, Shadwell, a relic of Victorian engineering that is as far removed from glamorous as it is possible to be. Murphy was holed up in a “luxury” trailer, with the heating set to furnace, drinking mugs of herbal tea. The shoot had gone well and he was in a bonny mood: “I actually like taking pictures. I love trying to find the mood with the photographer and the stylist. When it’s a collaborative thing.” Murphy is now 47, with greying hair and a slight ruggedness about the eyes. He’s still absurdly handsome, especially when dressed in his off-duty sweater, jeans and workman boots.

In early February, Murphy was at the midpoint of the awards campaign. He was jetting back and forth from Hollywood for countless dinners and meet-and-greets, and dozens of ceremonies that would make the presidential trail seem tame. His odds for winning had become a near done deal, his fame had reached another tier. In Ireland, he had reached the zenith of recognition: his former primary school had swagged the school gates in a banner wishing him good luck at the Academy Awards.

For a man who has always steadfastly avoided press attention, the new scrutiny found him somewhat overwhelmed. “He is the world’s best actor and the world’s worst celebrity,” said his co-star Emily Blunt recently when asked about his attitude to fame. Murphy acts like a spooked cat around most journalists; he has no social media platform. He specialises in an expression poised between disappointed and bemused. “Everyone knows that I’m the most fucking memed awkward person on the internet,” he cringes when I mention a TikTok that sees him ambling into the Golden Globes alongside the caption: “When you made plans while you were feeling extroverted and now you have to attend.” “Can’t I just be normal?” he says. “It is nuts, you know?”

In spite of appearances, however, Murphy has been having fun: he’s even allowed himself to have been photographed in public with Yvonne, a very rare occurrence in their 20-year marriage. “I am enjoying it, because I’m choosing to enjoy it, and I think there’s a distinction,” he says. “And this is celebrating the work that we did, and you have to go into it with an open heart.”

He reminds me of another Cork-born legend, the Irish midfielder-turned-football pundit Roy Keane. Both share the same congenital disposition to seem utterly nonplussed. “[Roy Keane] is actually one of my favourite people,” says Murphy. “I met him once in an airport, and we had a very intense chat for about an hour and a half.” Did he see a kindred spirit? “I did,” says Murphy. “He’s got that thing, that Cork sense… straight to the heart of the issue. He’s a legend. Everything he stands for, I love.”

Murphy’s route to acting was one part accident, three parts drive: the eldest of four children to teacher parents, Brendan and Mary, he grew up in Cork city, in the south of Ireland. His first creative outlet was playing in a band. “Music for me is a pleasure,” he says (he still presents a show on BBC Radio 6 when time allows). “I’ll do anything that involves music… even just making mix tapes or making radio shows or being in music videos. Really, it’s a primal thing.” It is, he says ruefully, the career that got away. “It’s funny, recently my dad found a load of VHS tapes of the band’s earliest days. We were 15 or 17. It’s all I wanted to do. I was completely eaten up by this need to make music and be a musician. To just be up there and play the songs.”

When the band (including his 16-year-old brother) were offered a record deal, his parents “scuppered” the plan. He then started a short-lived law degree before his natural curiosity led him towards the stage. He badgered a local director to give him an audition, and got a part. Not long after he was touring Disco Pigs across the world.

Murphy has always been single-minded about what he wants to do. He has boundless energy and focus. When he’s trying to get his head into a project, he’s been known to go for multiple runs (he used to run 10km distances competitively), although today he’ll more likely walk his dog, a black Lab called Scout. “I don’t think it’s ambition,” he says when asked if he is goal-oriented. “But I love challenging myself. And if you get to a level at something, you go, ‘Oh, what if we push this further and go to the next level and see what happens there?’”

It’s one of the reasons he admires Christopher Nolan: he shares the filmmaker’s unsparing efficiency and desire to get things done. “I’ve never seen a more effective use of time on a film set, ever, in my whole career,” he says. “Film sets are so wasteful normally, it’s like a picnic, everyone just sitting around eating snacks. It drives me mad.” By contrast Nolan has established an accepted culture in which everyone is there to work. “No phones, real locations if possible, so you don’t have guys standing around with lights and scrolling phones. He keeps the catering miles away from the set. It focuses everybody. Everyone expects excellence, because he delivers excellence all of the time.”

Seen in retrospect, Murphy’s career has seemed very fluid. He endured a couple of years of unemployment in his 20s, but in 2002 Danny Boyle cast him in 28 Days Later, an apocalyptic thriller that became a cult classic, and he’s been pretty busy ever since. In 2006 he was nominated for a Golden Globe for Breakfast on Pluto, and starred in Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes the Barley, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Peaky Blinders brought him to a whole new audience, as have the Nolan films, but his career has been a slow maturation to greatness rather than an overnight success. “I am really glad that it [the awards campaign] happened to me now, and not when I was 20,” he says. “I’ve been acting for a long time. I don’t think you’re wiser, but I have perspective. If it had all happened in my 20s, I wouldn’t have been able to handle it very well.”

His latest role is much more fun. He is currently the face of a new Versace Icons collection, picked by Donatella Versace and shot for the campaign by Mert & Marcus. Murphy enjoys clothes and fashion. He spent six months working with archive Versace looks: he’s especially attached to high-waisted trousers (see his many red-carpet appearances), and the tailoring that marked the early ’90s at the house.

Hit for six

Versace first became aware of Murphy as Scarecrow in the Batman movies: she’s also a big Peaky Blinders fan. “I wanted to collaborate with someone unexpected,” she says. “It was so interesting to work with him. Cillian loves clothes, and understands and appreciates the subtle details – he has an instinctive taste and natural eye for style.” As for what makes his screen presence so magnetic, she refers, as everybody does, to those steely blues. “There is something magical about Cillian that I instinctively connect with, and his mesmerising eyes of course.”

Murphy’s own personal style has been honed via costume, nowhere more than in his Peaky Blinders guise; there have been few other wardrobes as influential as Thomas Shelby’s, with his great coat, mad undercut and swaggy totems of old-timey gangster style. Murphy first donned the cap in 2013 and will likely wear it again when the long-promised Peaky film transpires. “There’s a lot of momentum,” says Murphy of the feature that will start filming in September. He says he’ll do it if “there’s a great script” and “more story”. But when pressed for confirmation of his reappearance he insists there’s “nothing official yet”.

Oppenheimer has brought other opportunities. Weeks after our first meeting, I saw Murphy at the Berlin Film Festival, where he was opening the Berlinale with the film Small Things Like These, an adaptation – by Walsh – of the Claire Keegan novel. Murphy was there as that film’s lead actor and its co-producer, a debut project under the banner of his new film company Big Things Films. Small Things was produced with Matt Damon and Ben Affleck (he pitched it to Damon while they were on a night shoot on Oppenheimer), for a modest budget of less than $10mn, and focuses on a community being witness to decades of institutional abuse. A counter to the bombast of Oppenheimer, it is tiny, quiet and cerebral. But Murphy’s performance, as a family man wrestling with his conscience, is one of the best of his I’ve seen.

Then comes Netflix’s Steve (another adaptation, this time of Max Porter’s Shy), which he will also star in and produce. He’s collaborating with the director Tim Mielants, with whom he worked on Peaky Blinders, and it’s another role based on a man poised on the edge. Murphy is drawn to anguish, and roles that tickle the darkest recess of the human soul. This, combined with his professional intensity, means it’s easy to forget that in private he’s a total goof. He’s an incredible mimic, and loves dad jokes, wordplay and godawful puns; I’ve often said that if the work dries up in acting, he’d be a great headline writer at The Sun.

“I don’t know where I read the quote: it takes 30 years to make an actor, but I believe that,” says Murphy of the roles that he now seeks. “It’s not just technique or experience or any of that, but just a life lived. I remember there was a weird transition when it was like, ‘I’m the dad guy now?’ But, as the dad of teenage children, I’m very comfortable playing a parent now.”

As for technique, he still draws on the same gut reflex. “Instinct is the thing I rely on most,” he says. “Everyone is obsessed with process. But I’m much more interested in outcome – that’s all that matters. What I do in the rehearsal room… just happens. It’s all about energy and being in the right frame of mind.”

The last time I spoke to Murphy was two days after the Oscars ceremony. He had arrived in New Zealand with Yvonne and Aran, currently acting in the new Taika Waititi film. Murphy had “catastrophic” jetlag, and was still feeling “pretty dazed”. Following one of the “longest awards seasons in history”, thanks to the actors’ strike, he was still getting used to having the statuette in his life. “It’s bizarre. I see it and think, ‘What the fuck’, and get a shock.”

On the Academy stage he thanked the room in Gaelic, and spoke of being a “proud Irish man”. What was the significance of being the first Irish-born actor to be awarded for a leading role? “The Oscars looms very large in our cultural landscape,” he says. “I remember as a kid when Daniel Day-Lewis and Brenda Fricker and Neil Jordan [other Irish creatives] won. They’re massive. And I felt very strongly about my Irish identity: it was very prominent in my thoughts, because it’s an American awards ceremony, and you do feel as though you are representing. And because you’re aware of how much people at home are invested in it. You want to be the best you can.”

Murphy never set out to win an Oscar: “You’d have to be a bit strange if that’s how you felt.” Neither does this mean he’ll move to Hollywood and join the LA scene. He doesn’t really differentiate between different acting cultures in the course of what he does. “I’m just part of a big ecosystem. Sometimes you work in a studio in Los Angeles, and sometimes you’re on a tiny indie set. Sometimes you’re in a theatre. And sometimes you overlap. But really, you work how you work,” he says. “You have your value system. ‘Hollywood’ is something you only read about.”

Normal life now beckons. He can retreat into his introverted self. He can grow a beard, and eat and sleep again, and go for long solo walks in Kerry where he and Yvonne have a second home. He was hugely boosted by Yvonne throughout the season; the role of supporting spouse should also get an award. He was also delighted to have his whole family on the red carpet for the big night – his best mate and his younger brother flew out to surprise him, too.

“Emily [Blunt] is a best friend – and [Robert] Downey [Jr],” he says of the “surrogate family” who have been with him throughout. “I couldn’t have got through it without them. They’re such good people, I’m really lucky. Also, we had a laugh.”

After so much campaigning and producing and planning, does acting still give him the thrill? I think back to that feral actor at the Traverse and whether he can still tap into the brilliant raw emotion he had then. “I still get chills,” he says of live performance. “The magic still exists. Even when you know how the cake is baked, you still enjoy eating it. Do you know what I mean?”

Grooming, Gareth Bromell at WSM using Sisley Paris. Photographer’s assistants, Pedro Faria, Seb McCluskey and Georgia Williams. Tailor, Allison Ozeray. Stylist’s assistants, Amy Jolly and Lacie Gittins. Production, Rachael Evans at RE.Pro

Comments