Sydney’s HIV success shows way for others

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The near-elimination of HIV transmission in inner Sydney last year was a remarkable achievement, not least because there is no vaccine or cure, and the city was once one of the epicentres of the disease.

Experts say it resulted from the commitment of clinicians, activists and politicians to deploy the preventive tools that are currently available — and that it shows just how effective those tools can be. They comprise regular testing, education on safer sex, prophylactic drugs that block transmission, and giving treatment to people living with HIV because it prevents them passing the virus on and enables them to live long and healthy lives.

Some 39mn people worldwide are living with HIV and 1.3mn were infected last year. The virus disproportionately affects people in Sub-Saharan Africa and men who have sex with men.

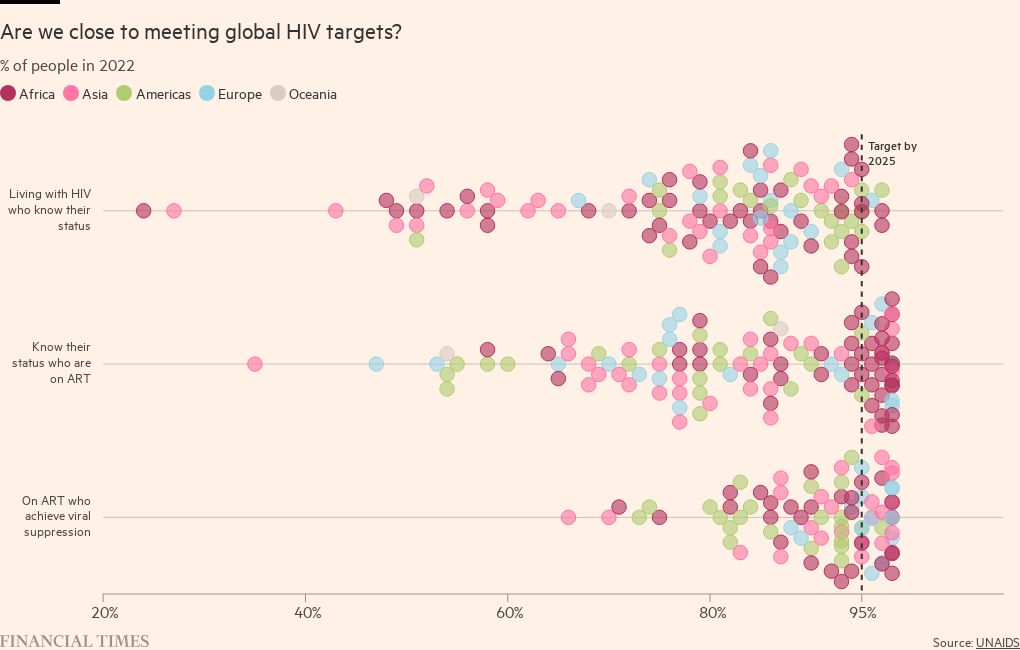

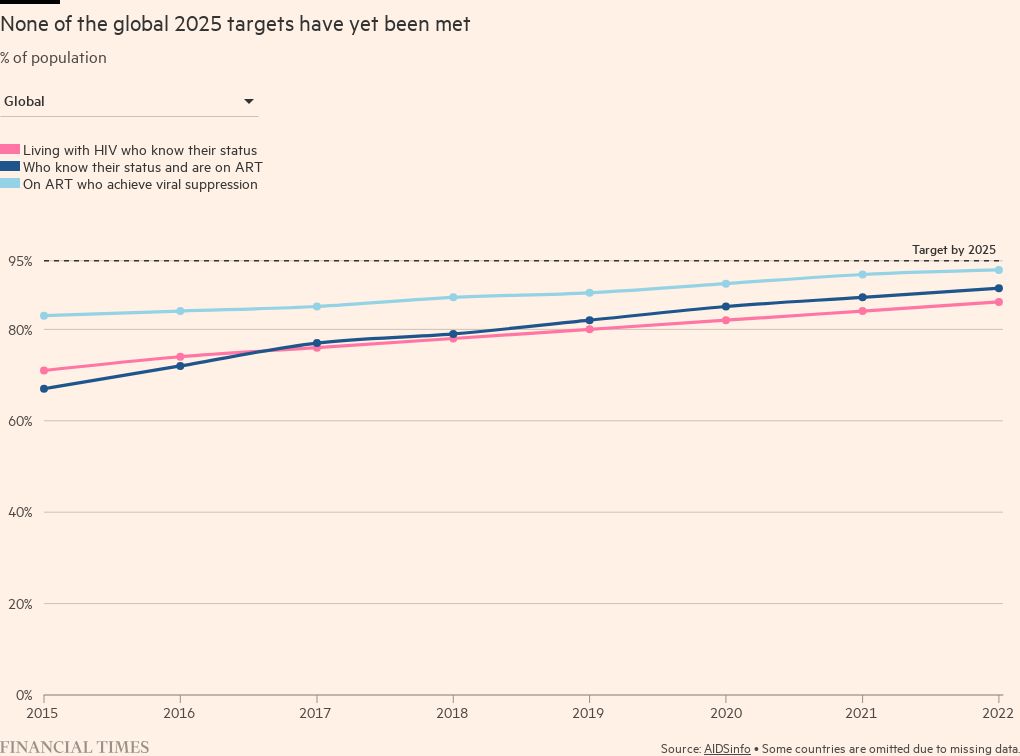

The UN has set global targets for 2025 of 95 per cent of people with HIV knowing they have it, 95 per cent of that subset being on drug treatment, and 95 per cent of them achieving suppression of the virus to undetectable levels.

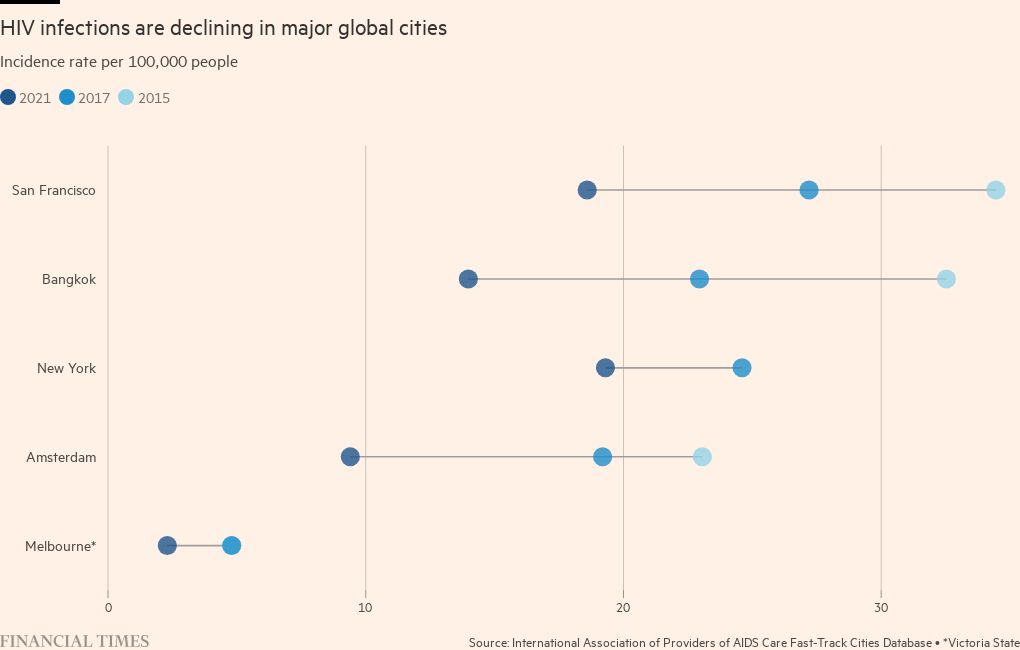

Some countries, particularly those with smaller populations and higher burdens of disease, have seen big falls in infections, and steady progress is being is being made at a global level.

Meg Doherty, head of the HIV programme at the World Health Organization, says “the secret sauce is political commitment”. While the numbers “can look relatively good in some places”, says Doherty, “as we start to look towards elimination [of HIV], we have to think about the entire population”, including those not identified or on effective treatment.

While it is a big achievement for about 70 per cent of people living with HIV to have suppressed the virus, that still leaves “30 per cent of people living with HIV walking around with the virus at some level that could contribute to new transmissions”.

The nations doing well against the targets have done so because of funding, leadership and collaboration between civic society and politicians, say experts.

“These are the countries that had high rates . . . of deaths in the 90s,” says Doherty. “There’s a feeling of ‘We’re not going to go back there, we need to do all that we can do not to go back there’.”

The reasons why countries do badly include lack of funding and repressive laws that discourage important sections of the population from engaging with health services. “We have pockets of great success, and we have pockets where HIV has been ignored,” says Doherty.

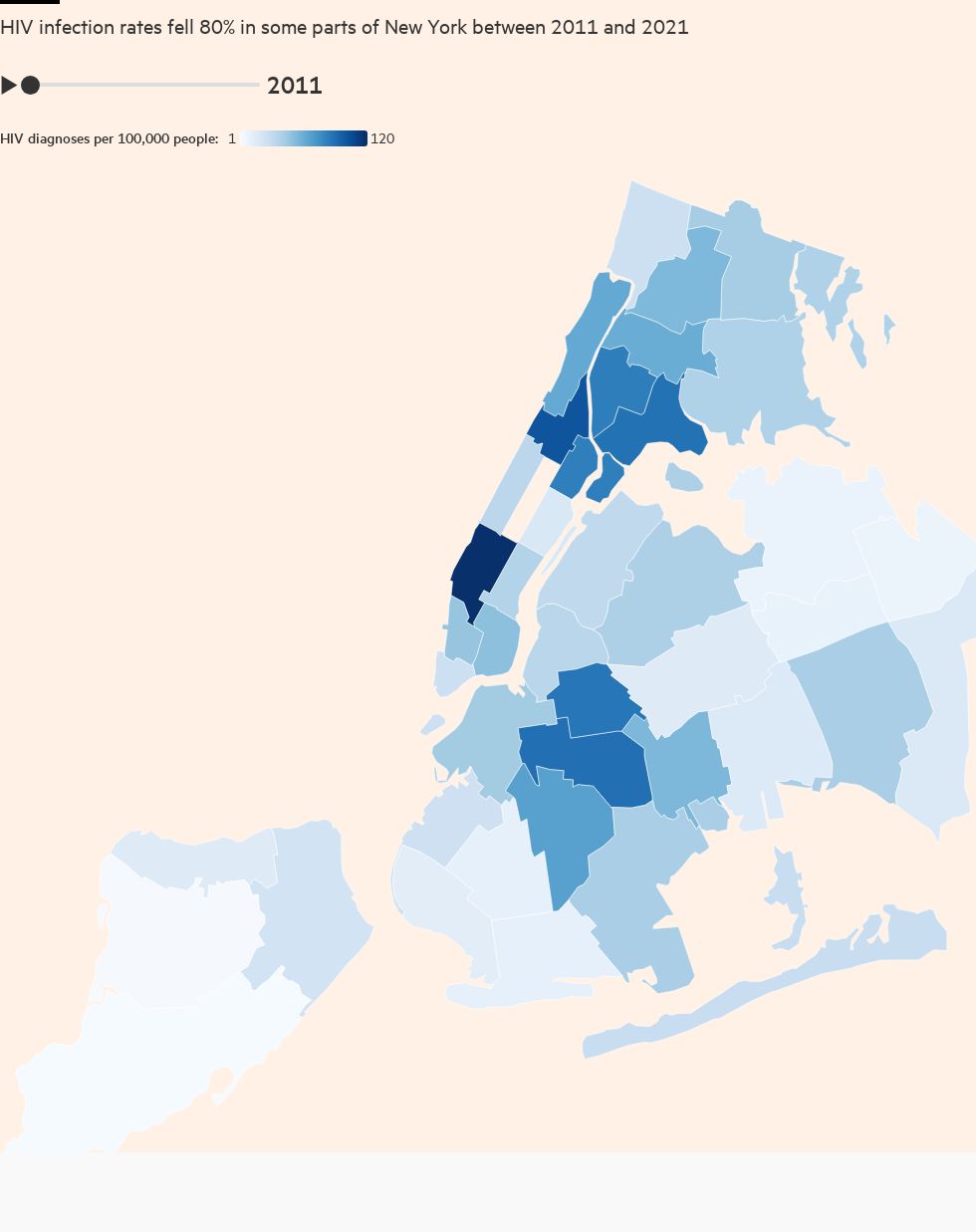

The fall in infections has been greatest in certain big cities that were early epicentres for the disease, such as Sydney. Will Nutland, co-director at UK health promotion charity The Love Tank, says that in cities such as Paris, New York and London, activists campaigned for the introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drugs. “When HIV PrEP is introduced alongside other HIV prevention technologies, we see massive drops in HIV acquisition,” he says.

Yet there remains a risk that complacency could lead to progress being erased. “The challenge now is to ensure that we do not assume that the job is done: there are key groups of people who could benefit from PrEP who are missing out — this includes trans people, [cisgender] women, migrants, and younger queer men,” says Nutland. He calls for governments to ensure sustained funding for HIV prevention, provide it beyond clinical settings, and support community activists.

“Globally, we have the ability and tools to move to preventing new HIV infections,” he adds. “We need the political willpower to make it happen.”

Comments