Collector Leo Shih on his search for rare 20th-century Chinese art

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I first met the Taiwanese art collector Leo Shih last year, at the inaugural edition of Taipei Dangdai. He was, and is, a force to be reckoned with: in addition to being an adviser to the contemporary art fair, he’s one of Art Basel’s so-called “Global Patrons”, and assists other fairs and museums. “I’m always happy to help!” he says.

Indeed, when we speak on the phone a year on, just before the second edition of the fair gets under way, he’s jovial and friendly. “Collecting art is my hobby, not my business,” he insists — that business being a trading and hardware company, which he founded in 1989 in the central Taiwanese city of Taichung.

Shih seems to have inherited the collecting gene from his father, a noted stamp collector, and by the age of seven he, too, was into philately. His first art purchase was in the 1990s, a wooden sculpture of the Buddhist goddess Guanyin. “At that time I didn’t have the means to pay much, but I really liked wood carving,” he explains. “And it was a friendly price.”

As Shih’s business prospered, so did his collecting ambitions, and in 1998 he made what he calls his first “fine art” purchase — a painting of rice fields by the Taiwanese artist Huang Ming Chang. Then came a work by the early 20th-century Chinese-French painter Sanyu, acquired at Sotheby’s in 1999. Those were the last auctions held by the auction house in Taipei before it shifted business to Hong Kong, the rising star in the region.

Since then, Shih has maintained his focus on the first generation of Chinese oil painters, while extending his interest to contemporary Asian artists, even some international names.

His collection now numbers over 2,000 works, kept in a series of apartments and rotated frequently, with the core holdings kept in his family home in Taichung.

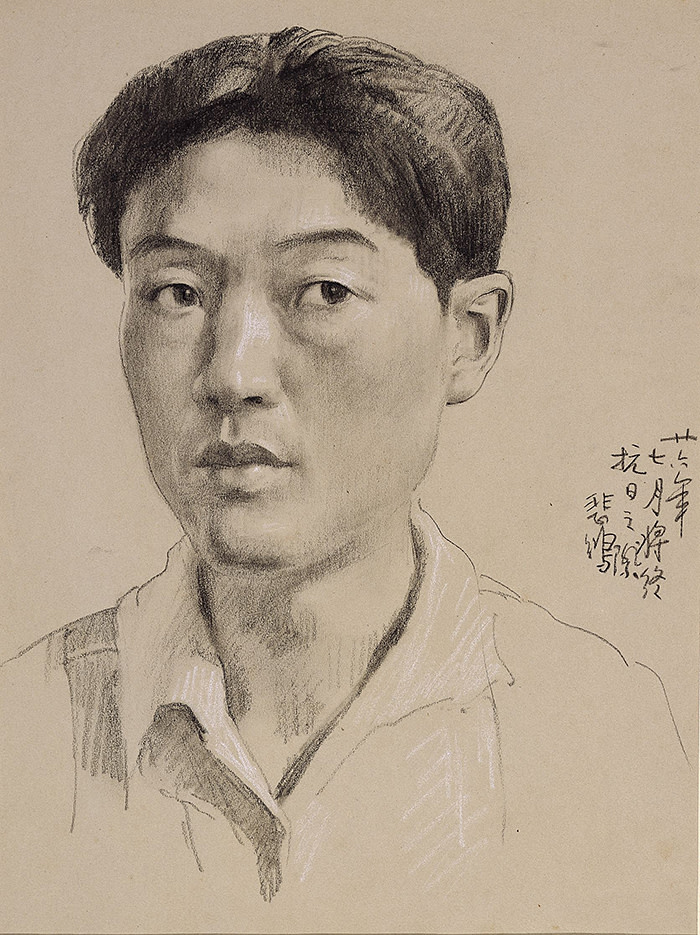

Shih explains his fascination with the period: “In the early 20th century, China was undergoing upheaval, in the period between the end of the Qing dynasty and the republic. It was a mess.” One result was that a wave of art students went to Paris and absorbed the influence of western art, among them Sanyu, Xu Beihong, Lin Fengmian, and Yan Wenliang — all artists whose work now figures in Shih’s collection.

Almost all these artists, Shih explains, came back to China, “eager to teach what they had learned, and to give something back”. But just as they returned, there was more upheaval: the Japanese invasion of 1937, the second world war, the civil war that brought the communists to power on the mainland in 1949 and the founding of Taiwan as a separate republic.

By the time of the Cultural Revolution, these artists’ espousal of western techniques and subjects put them in grave danger. Many were forced to destroy their art. “A lot of work went missing,” says Shih, citing as an example Lin Fengmian, who soaked many of his artworks in water, and then flushed the pulp down the toilet of his Shanghai apartment, “afraid they would be found.” Lin went to prison anyway, although he was finally allowed to leave China in 1977, once Mao was dead.

Finding and acquiring such works today is a challenge, but Shih says it is important to preserve this piece of China’s art history: “At the beginning there were no books, and I had to find paintings piece by piece, mainly through families or at auction.”

Over the 20-odd years he has been collecting, more and more information has come out: “When I started, there was very little contact between China and Taiwan. Now it’s better and there are people studying the period,” he says. “But there are still very few works available.” Given this scarcity value, prices can reach the stratosphere — in November last year, Sanyu’s “Five Nudes”, dating from 1955, made an exceptional price of HK$303m (US$38.72m) at Christie’s Hong Kong.

Long before that, around 2000, Shih realised that, instead of attempting to get hold of these first-generation Chinese artists, “in order to keep my hobby going” he had to refocus. So he started buying contemporary names — mostly, but not exclusively, Asian.

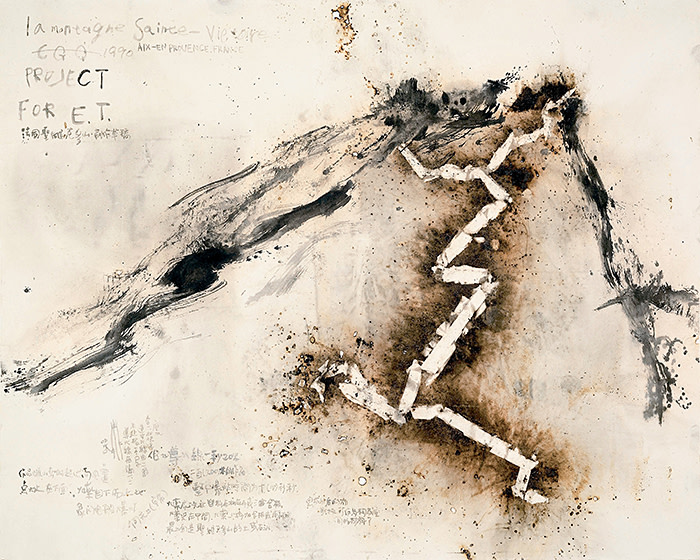

Among the artists he has collected are Richard Lin, Hong Kong’s Lee Kit, Haegue Yang from Korea and Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, Chen Zhen and Gu Wenda from China — “but everything is so expensive now,” he says. Among his holdings there is also a smattering of western names: Shih mentions Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin as well as the Vietnam-born, Denmark-based, Danh Vō. The video works he owns include Nam June Paik and Bill Viola.

How does he see the future of his collection? Might it become a museum?

“A museum is quite a big thing for me,” he replies. “I used to think about this, but to build one is easier than to maintain it — that’s the hard part. I don’t think I will go that way. At the same time, I feel I am responsible for letting the world know how important this first generation of Chinese artists is. They are the missing link in art history. My job is to show them to the world, perhaps alongside Chinese ink works.”

Shih has two children, both involved in his company — neither of whom has much time to indulge a passion for art. “They have to work!” he laughs. But he adds that they might pick up the baton and make a museum happen. “I think that an exhibition will be my job, and to do a museum will be their job …”

He regularly visits Asian fairs such as Art Basel Hong Kong, West Bund and 021 in Shanghai, as well, of course, as Taipei Dangdai.

As for trips to the west, he says he hasn’t been for three or four years. I ask him if this is because so much more art has come to Asia through these art fairs. He explodes with laughter. “No, not at all. It’s because of my business!”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to Culture Call, the FT’s culture podcast, which interviews people shifting culture from London to New York. Subscribe at ft.com/culture-call, Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Comments