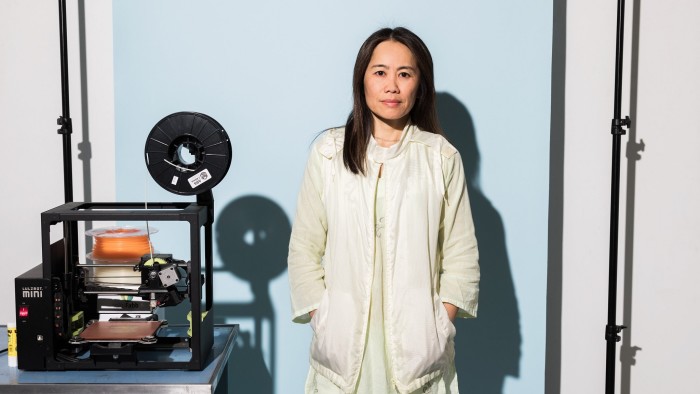

Artist Shirley Tse’s ‘models of multi-dimensional thinking’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Wood!” It was hard to contain my surprise. I’d walked into the studio of Shirley Tse, in the Inglewood district of Los Angeles, expecting to meet the queen of plastics. A sculptor and installation artist who had made her name, and won plenty of acclaim, using plastic, polystyrene and other everyday mutable synthetics in her work. Instead I find her, a neat figure who combines the elegance of her Chinese heritage with the relaxed vibe of her adopted California, surrounded by turning lathes.

“I didn’t know you worked in wood.”

“Neither did I!” She laughs. “It’s definitely new for me.”

She sets out to explain the path that has brought her here.

“Though I’ve become known as the artist working with synthetic materials, I don’t really see myself as only focused on materials — from the get-go it’s always been about both idea and material, both concept and object. At some point people decided to describe my work as very material-oriented, it’s quite irksome really. Because even at the beginning, when I was using a lot of plastic and styrofoam, I chose that for a reason — how it signified globalisation, movement — and most importantly, paradoxes.

“It’s such an interesting substance. It’s temporal in use but permanent in substance. It’s something we see everywhere, but it’s so alien. This is a material that at one point was totally utopian, but within a span of 20 years had become totally dystopian. It’s a substance that embodies all these paradoxes . . .

“So the new work I’m doing is really a continuation, a way to continue to work with that multiplicity.”

Multiplicity, I quickly realise, is at the heart of Tse’s thinking. Her workaday studio has shelves of books; she quotes philosophers and literary metaphors as well as science. An easy fluency with the emotive language of art coexists with a more analytic eloquence — she is, after all, a professor in the School of Art at California Institute of the Arts.

Many-strandedness was also at the heart of Tse’s last show — Lift Me Up So I Can See Better, based loosely on the Oscar Wilde story “The Happy Prince”, which is replete with metaphor: social, emotional, human, political. Here her materials included glass, copper, found objects and more, and incorporated narrative and figuration in pieces that, she says, explored “verticality”. Proof, perhaps, that you’d pigeonhole this artist at your peril.

2014’s Quantum Shirley, too, was a show that crystallised Tse’s fascination with quantum physics and the ideas of multiple worlds and parallel realities. That differences coexist.

“Getting older,” she says, “you think about choices and crossroads and the path you didn’t take. I was reading a lot about quantum theory and I realised, you know what, that path did exist, I just don’t have access to it. I find that idea very poetic and powerful — but also how crazy is it that now science gives validity to that kind of thinking, which would once have been so outlandish.”

We circle back to the journey that brought her in the early 1990s to California from her native Hong Kong, where she grew up the fourth child of factory-working parents. She tells me a convoluted history of diasporic labour. “My parents weren’t even really Chinese: I have very little connection to mainland China, actually. Well in fact they were Chinese, but my dad was born in Indonesia, my mom in Malaysia. My mother’s family had gone to Malaysia to work on the rubber plantations, run by the British, then the family moved to the South Pacific, to work for the French on vanilla bean plantations — so my family were part of global trade movement, colonial products . . . no wonder I’m interested in plastic!

“It all makes sense to me. But the idea is so huge, I couldn’t put it all in one single work, it has become a series. It’s like a framework to express my personal story, how science can make sense of imaginative vision, the movement of colonial trade, the history of the Chinese diaspora . . .

“And now in my recent work I really want to focus on how things are put together, how they negotiate with each other to form some sort of structure.”

All her sculptures, she has said, are “models of multi-dimensional thinking and negotiation”. Yet the sheer materiality of things is never far from her mind. Suddenly excited by the wood, she jumps up to show me turned objects — a bottle, a baseball bat — that will form part of her site-specific piece for the forthcoming Venice Biennale, where she will represent Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong pavilion, which stands directly opposite the Arsenale, is an inside-outside courtyarded space, and the solo exhibition, entitled Stakeholders and curated by Christina Li, consists of two elements. A model of “Negotiated Differences”, formed of different weights and lengths of curving wood, joined by special 3D-printed links and punctuated by everyday objects (bottle, part of a prosthetic leg, drinking cup, tampon) turned in wood, shows an elaborate modular winding structure — an endless series of connection, a journey without start or finish — that will weave through the entire space, and erupt into the courtyard with “Play Court”, a set of strong vertical structures evoking radio masts, ships’ masts, watchtowers and more.

As usual, Tse sees the work as a merging of literal and abstract ideas and, of course, Venice’s particular identity as a historic trade nexus strongly evokes the convergence of colonialism and product, displacement and trade. “Some of the work addresses the actual narrative, elements of it address the idea of going between two places. Those confluences . . . ” she says.

And those paradoxes, again.

Venice Biennale, May 11-November 24

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments