Automation can help humans enjoy happy, productive working lives

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

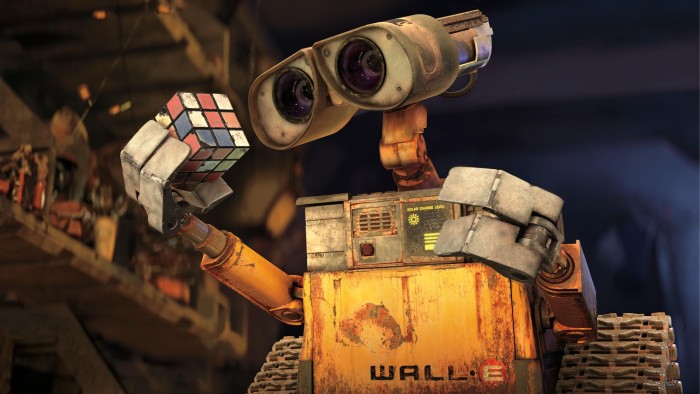

Is a robot going to steal your job? Posed like this, the “fourth industrial revolution” looks relentlessly negative. We are all familiar with the dystopian scenario. Mass unemployment, accelerated inequality, widespread redundancies and workers left without purpose as the machines take over. This bleak picture troubles those who look beyond short-term political cycles at how technological trends will shape our society and our economy in the decades to come.

But let me ask a slightly different question. What mundane tasks would you willingly pass off to a friendly robot helper? What don’t you like doing at work — organising your calendar? Checking for meeting rooms? Filling out forms? And what would dumping these tasks — on to an artificial intelligence underling — free you to do more of in your work? The stuff you enjoy, probably, and the bits that are actually productive.

The truth is that automation and AI are coming (indeed, they are here) whether we like it or not. We don’t really have a choice. But that is not to say that we lack all agency about when it comes, how work will change or the impact of the coming revolution. Whether the inevitable robots replace us at work or make our work happier and more rewarding — that is in our hands.

At the Institute for the Future of Work, we are not very interested in the question of whether new technology is utopian or dystopian — because it tends to be what you do with it that really counts. We are engaged in building the tools and the processes to help employees collaborate in identifying how automation can make work better and more productive, ensuring the jobs we have are good for boss and worker alike.

This means designing the technological augmentation of tasks with the experience of workers as the priority; asking how automation can improve workers’ lives and enhance productivity, not how it can simply replace human work or create new processes that alienate human beings from the world of work. We think this will be crucial in helping Britain cope with the double disruption of Brexit and the AI revolution.

Companies that get this right have a huge amount to gain. The Sony UK technology centre in Wales managed to increase productivity by automating some of its production lines and redeploying workers to upskilled roles. Research published last year by a team led by Chris Brauer at Goldsmiths, University of London, showed that organisations augmented by automation technologies are 33 per cent more likely to be human-friendly, and have employees who are 31 per cent more productive. That’s an astonishing double-win: happier employees, assisted by technology to get a third more done with their time.

All this requires a change of mindset. If we are to harness automation for human ends, and avoid driving people out, we must think in systems from the outset. This means looking at work within organisations from all angles — involving workers, employers and other stakeholders, such as consumers, in designing technological augmentation.

Recognising the inputs and outputs of a particular job, carving out elements where automation would be welcome, can set workers free to achieve more. Conducting this process in reverse — working out what we can automate quickly and leaving the remainder for humans to do — is a recipe for misery, alienation and social decay.

We are focused on building the tools to help employers do this right. Our Good Work Charter helps to define the principles of what a good job looks like. Bodies such as EUnited Robotics — the trade body for the European robotics industry — are adopting the charter to create practical guidance to help engineers think about the impact of their designs on people.

In the end, the fourth industrial revolution will bring with it massive new automation. It will not drive humans from the labour market entirely. But the choice will be between human workers left to sweep up after robots and robots who are there to boost happiness and productivity for workers. This will not happen organically; it needs us to be vigilant and to design the tools and the processes to tell the difference between these two approaches. But the prize is real and hugely exciting. I, for one, welcome our new robot underlings.

The writer, former president of the Institution of Engineering and Technology, co-chairs the Institute for the Future of Work

Comments