Poverty, open sewers and parasites: ‘America’s dirty shame’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Martin Luther King led civil rights activists on a march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965, he charted a route through Lowndes County in Alabama. This sparsely populated rural area is one of the poorest places in the US. Some residents cannot afford waste water sanitation facilities, and so must allow the sewage from their mobile homes to flow freely into their backyards. Human waste lies uncovered in soil. Children play nearby. This is “America’s dirty shame”, according to Catherine Flowers, a local community activist and director of the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise.

Concerned by the health implications, Flowers asked scientists at the National School of Tropical Medicine in Houston, Texas, to conduct experiments in the area. The research will soon be submitted to the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. “They tested the soil and water, and took blood and faecal samples. They found at least five tropical parasites,” she says. The poor living conditions are exacerbated by a climate that combines increasingly high temperatures with heavy rainfall, creating a good environment for parasites to breed. “It is the perfect intersection of poverty and climate change,” she adds.

Flowers worries that the problems will only become worse if President Donald Trump cuts the budget of the US Environmental Protection Agency as planned by 31 per cent. He has already ordered a review of clean water rules introduced under Barack Obama and plans to abolish entirely the Fogarty International Center, the global research arm of the National Institutes of Health.

Alabama is one of the five Gulf coast states that shoulder the burden of neglected tropical diseases in the US. Some scientists say these are an under-appreciated problem in the world’s largest economy. Among the parasites found in Lowndes County were helminths — intestinal worms that infect humans and are transmitted through contaminated soil, such as hookworm, whipworm and ascaris. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says hookworm was widespread in the southeastern US until the early 20th century and is now “nearly eliminated”.

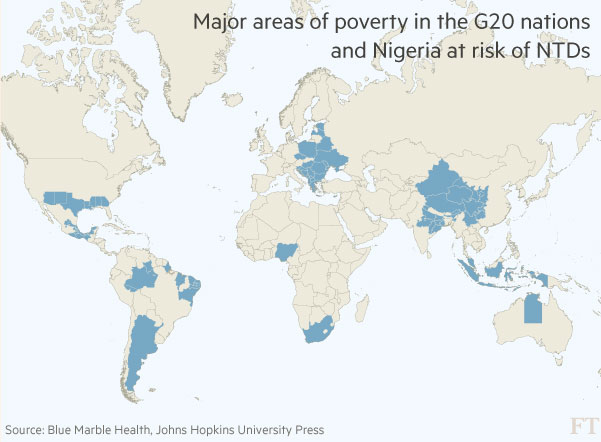

But Dr Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine, warns against complacency and estimates as many as 12m Americans are living with a poverty-related neglected tropical disease. “Most of the world’s neglected diseases are in the world’s G20 countries,” he says. “The concept of global health needs to give way to a new paradigm: on the new map, Texas and the Gulf coast would be lit up as a hotspot.”

Hotez’s department is located among more than 50 institutions clustered in gleaming tower blocks on the banks of a stream. The only thing that might be considered “tropical” about the area is the nearby Houston Zoo. But it is just a 20-minute drive to Worms Street in the city’s Greater Fifth ward, nearly half of whose residents live below the poverty line.

Many of the shops and homes are empty and derelict, while front gardens are littered with rubbish. “If you drive through these poor parts of Houston, you’ll see housing with no window screens,” says Hotez. Such screens are essential to stop the spread of mosquito-borne illnesses such as Zika. “There are lots of other environmental risk factors — discarded TV sets and tyres that are full of water and provide a breeding ground for mosquitoes. A lot of it has to do with overcrowding.”

He notes that many of the areas affected have high levels of immigration, but argues it is wrong to blame migrants for spreading tropical disease given that the majority of US cases are transmitted domestically.

“This is not about immigration: we have the vectors, we have the climate, we have the poverty,” he says. “If this were happening in wealthy suburbs like Westchester, New York, we would never tolerate it, but because it’s happening in flyover America and the Gulf coast, people don’t care much about it.”

Hotez concedes that his figure of 12m Americans is an educated guess, and argues that a lack of good data is one of the biggest barriers to wiping out the illnesses. “We have no surveillance, so we have no data,” he says.

Many of these diseases are also routinely misdiagnosed by family doctors who may not be trained to spot tropical diseases, he says. For example, Chagas, an infectious disease spread by triatomine beetles, also known in the US as “kissing bugs”, is often mistaken for coronary heart disease. Left untreated, it can lead to fatal heart failure. Even when physicians suspect a patient has a tropical disease, it can be difficult to make a firm diagnosis because many local laboratories are not equipped to test for the illnesses.

Hotez proposes a three-stage plan to eradicate tropical diseases in the US. First, the government should ramp up surveillance to better understand the scale of the problem. Second, it should ensure infected people are in treatment. Finally, scientists should develop “point of care” diagnostic kits capable of detecting these illnesses, to be used in doctors’ surgeries.

However, he is pessimistic about the chances of securing state or federal funding for such a programme. “The president has said he wants to cut $54bn across the federal agencies to provide funding for defence,” he says. If those cuts hurt agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the CDC, “it is not going to help anybody”.

But the problem long predates Trump, he adds. “To be fair, things were not particularly good under Obama, or Bush, or Clinton — this is a neglect that transcends the presidencies.”

Comments