Moroccan lenders shore up small businesses but risks loom

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To the good fortune of Morocco’s small businesses, the country’s banks were ready to help them through the pandemic before it had even started.

In early 2020 — when coronavirus had not yet become a global emergency — the government unveiled an 8bn dirham ($900m) fund to finance small and medium enterprises over the following three years, along with other measures to simplify and speed up business loan applications.

The measures turned out to be a lifeline. “The banking sector has been really instrumental in financing the local economy,” says Jamal El Mellali, associate director for financial institutions at Fitch Ratings in London.

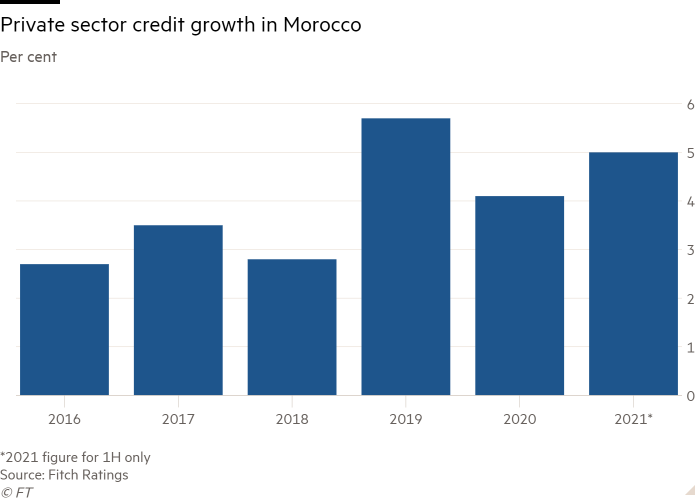

“Private sector credit growth in the first half of 2021 was 5 per cent, which is quite dynamic considering the economic conditions.”

Then, when the coronavirus crisis arrived, the initial measures were quickly superseded by two larger programmes, — Damane Oxygène and Damane Relance — which together extended loans at subsidised rates, amounting to more than 65bn dirham by the end of June this year.

Government guarantees covering 80 per cent of loan values under the initial scheme were extended to as much as 95 per cent under the two pandemic programmes — which gave banks the confidence they needed to keep private sector lending growth in line with recent averages, according to El Mellali.

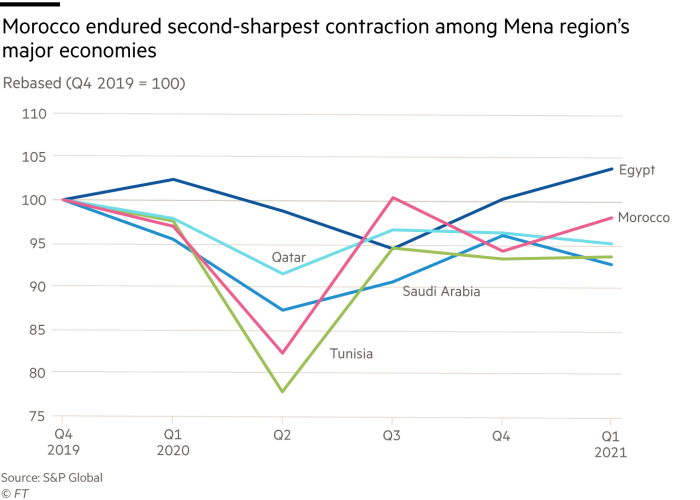

Morocco was hit particularly hard by the pandemic, in part because of its relatively high reliance on tourism. Of the six major economies in the Middle East and north Africa, it suffered the second most severe downturn in 2020 — a contraction of 6.7 per cent, smaller only than the 8.6 per cent seen in Tunisia, according to S&P Global Ratings.

Activities related to hotels and restaurants were 57 per cent below pre-pandemic levels last year, according to S&P — the biggest contraction in the region.

Now, though, S&P expects the economy to grow by 5 per cent this year, and by more than 3.6 per cent for each of the next three years — putting Morocco’s recovery behind only that of Egypt in the region.

Even so, Goksenin Karagoz, S&P’s director of financial services ratings and analytics for central Europe, the Middle East and north Africa, reckons support from the banking sector is likely to come under strain.

“We expect credit growth to lose steam as the state-guaranteed loan programmes finish and their boost reduces,” he says. Damane Oxygène ended at the end of last year and Damane Relance closed at the end of June 2021.

That will be especially tough on small businesses, which employ about half of the Moroccan workforce, produce about a third of the country’s exports, and deliver about a fifth of the value added in the economy and of government corporate tax revenues, according to Fitch.

That may mean an increasing reliance by Moroccan banks on their overseas operations. The three biggest banks — Attijariwafa Bank, Banque Marocaine du Commerce Extérieur and Groupe Banque Centrale Populaire — control about two-thirds of the domestic market but have between a quarter and a third of their assets in sub-Saharan Africa, according to Fitch.

Taha Jaidi, head of strategy at Attijari Global Research, a subsidiary of Attijariwafa, says that, after more than a decade of internationalisation, “Moroccan banks are brilliantly distinguished by displaying one of the best long-term returns of the global banking sector”.

Nevertheless, says Fitch, the greater appetite for risk among Moroccan banks willing to operate in countries such as Ghana and Kenya means they tend to have a lower quality of assets than other domestically focused banks.

More from this report

Pandemic exposes vulnerabilities in Moroccan economy

Morocco’s carmaking prowess a result of shrewd state planning

Critics flag opposition weakness in Morocco’s new parliament

Morocco tourism struggles despite vaccine progress

Morocco asserts its power as diplomatic spats simmer

Casablanca financial hub’s fortunes tied to national economic strategy

The downside for the latter group — including banks such as Banque Marocaine pour le Commerce et l’Industrie and Crédit du Maroc — is that their market is comparatively saturated and stagnant. It is also highly concentrated, with about a third of activities in the retail sector and another third in trade, services and construction.

That leaves the banks “exposed to a few specific sectors and to high single-name concentration risk”, says Karagoz. “Despite some improvements, these risks remain elevated,” he adds.

On the positive side, funding for the sector is relatively cheap, with more than three-quarters sourced from low-cost deposits. The rest comes from Morocco’s capital markets, which are narrow by advanced-economy standards but sufficiently well developed to be a ready source of borrowing for the government and the banking sector.

But the sector faces a difficult time at least into next year. The rate of impaired loans at the country’s seven largest banks rose to 9.7 per cent at the end of 2020, up from 8.7 per cent at the end of 2019. Fitch believes the true picture was even worse, as banks were allowed to delay classifying loans as impaired, to support businesses in difficulty.

This year promises to be no better. El Mellali says the proportion of non-performing loans has continued to rise, as the pandemic pushes more businesses into default.

Comments