Indian microfinance gives birth to smaller banking model

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

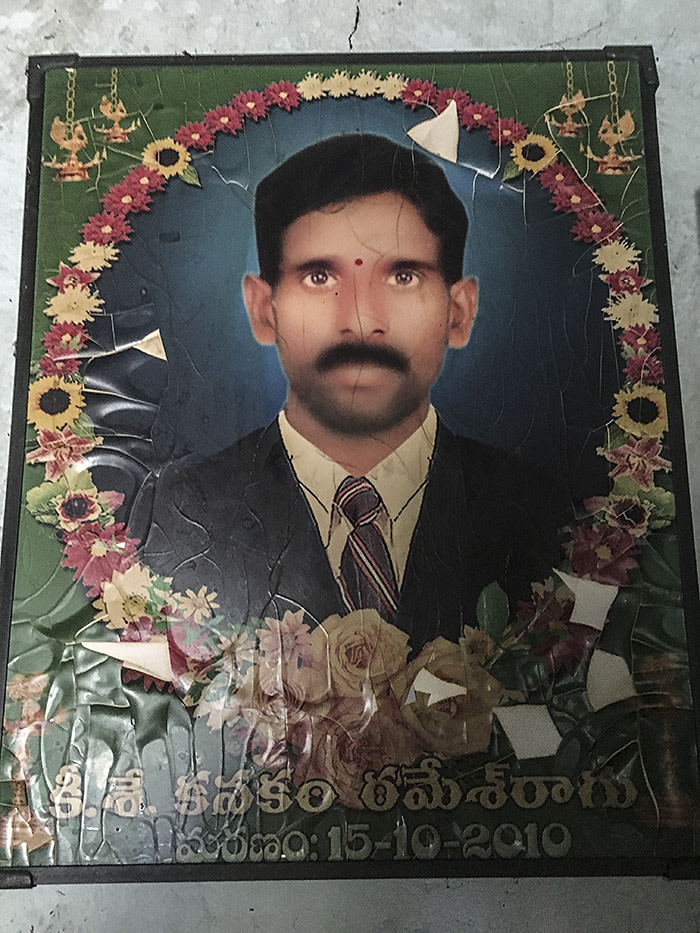

One morning in 2010, on his family’s two acres of dry land in southern India, Kanakam Ramesh, a 27-year-old father of two, hung himself from a mango tree. He had been involved in a bitter fight in his village over his wife’s inability to repay Rs36,000 (then about $750) borrowed from a company ostensibly dedicated to improving prospects for rural women.

Ramesh and his wife Rajitha were struggling labourers, eking out a living by working in prosperous farmers’ fields or at distant brick kilns, where they stayed for months during the brick-making season.

Two years previously, agents for private microlending companies from the city of Hyderabad had arrived in their remote village, peddling dreams of upward mobility — and urging women to take out easy loans to finance their ascent.

Initially, Rajitha took out two short-term loans of about Rs10,000 to help with medical expenses incurred by Ramesh’s aged mother. These debts were repaid without difficulty. But then Rajitha took out a third, larger loan of Rs36,000, starting a downward spiral that ended in tragedy, as Ramesh took his own life. “We thought it would be a helping hand,” Rajitha recalls eight years later, sitting outside her spartan home on a cool monsoon morning. “We had never imagined it could end like this.”

Ramesh was one of many over-indebted Indians who committed suicide in southern India in the autumn of 2010 — a spate of deaths that rocked the global microfinance industry, which was driven by social entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and impact investors who were convinced they were helping the poor.

Microlenders offered the tantalising promise that investors could “do well by doing good”. But critics claimed that aggressive Indian lenders — focused on rapid growth, profits and stock market listings — had pushed economically fragile families into debt traps. In the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh the suicides — and the public humiliation of defaulting borrowers — prompted the authorities to ban microlenders from collecting repayment on an estimated $2.7bn of loans, driving several large companies out of existence. Businesses elsewhere in India were hit too, as banks cut off credit flows to the sector.

Yet from this mess emerged a new architecture, as the Reserve Bank of India in 2015 issued licences for a new breed of small finance banks, mandated to provide an array of services, not just loans, to those at the bottom of India’s socio-economic pyramid.

“That rosy view we have of microfinance is over,” says Alok Prasad, chief executive of India’s Microfinance Institutions Network between 2010 and 2015. “The terminology has also moved on from ‘microfinance’ to ‘access to finance’.”

Microfinance was created in Bangladesh in the 1980s by economics professor Muhammad Yunus, who believed that lack of access to capital kept people mired in poverty. He argued that providing small loans to poor women to start tiny businesses could radically improve their lives.

Inspired by his pioneering Grameen Bank, scores of charitable groups across the developing world started small-scale microfinance projects, using Grameen’s “group lending” model, where small groups of women borrowed together and stood guarantee for each other, promising to cover the repayments of anyone who might default.

The UN designated 2005 the International Year of Microcredit, highlighting microfinance’s transformative potential. The following year, Yunus and Grameen were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Microfinance had garnered global accolades, and was being promoted as a virtual silver bullet against poverty.

But Indian microlenders were pushing what was once mainly a philanthropic activity into the commercial mainstream, led by Vikram Akula, an American entrepreneur of Indian origin, who in 2006 reorganised his Hyderabad-based charitable microlending foundation SKS as a for-profit company.

Backed by investors from Silicon Valley such as Sequoia Capital, Akula argued that the benefits of microcredit could only be spread adequately through commercial entities able to attract growth capital. Other non-profit Indian microlenders also converted themselves into companies, egged on by eager investors. “There was this huge euphoric mood around what microfinance institutions were doing,” says Prasad. “It was suddenly the trendy thing to do: you get this brightly shining halo over your head, and folks throwing cash at you.”

Between 2005 and 2010, India’s microfinance industry grew at an annual compound rate of 70 per cent. But in many villages this blistering expansion took its toll: much of the growth came from multiple lenders pushing out new, bigger loans to the same already heavily indebted women.

When stressed borrowers struggled to repay, they were bullied by company agents, who themselves were under pressure to maintain the industry’s traditional repayment rate of 99 per cent. Neighbours and co-borrowers, facing calls to honour their guarantees to cover those who failed to repay, often joined in the bullying.

“The old-style warm and cuddly connect with your client was over,” says Prasad. “When you have that kind of rapid growth, not even the finest management team can handle it. Your manuals may say the right thing, but to ensure that is happening on the ground is not the same thing. You are not always doing the right thing by your clients.”

For Kanakam Ramesh and his wife, easy access to credit led them to dig an expensive borewell, which they hoped would provide water for the family’s unirrigated land. But the well was dry, and the financial strain mounted. After Rajitha missed three consecutive loan repayments, her angry co-borrowers stormed her home one night, demanding she do whatever it took to come up with the cash. “I cannot even repeat the words they used,” she says.

Afterwards, she and her husband argued over who was responsible for their predicament, and she doused herself in kerosene to immolate herself. Her husband and neighbour stopped her. But the next morning, Ramesh hung himself in the field.

Following his death, Rajitha and her sons moved to her home village, where they lived for seven years with her mother. But she recently returned to her marital home to care for her ageing father-in-law, who had been left alone.

These days, she still works as an agricultural labourer, and often sees the women who pushed her to the brink. But none discuss the past, and Rajitha says she harbours no grudge. “I blame the microfinance companies and their methods of collecting instalments,” she says. “If somebody didn’t pay, they would build up pressure on the entire group. The women were provoked by the [lender’s] staff to do this.”

In Bangalore’s Chandra Layout neighbourhood, Nagamma, a 53-year-old housewife, sits in a brightly coloured branch of Ujjivan Small Finance Bank, as she is presented with an ATM card for her new account.

Nagamma runs a tiny tailoring business, selling cloth, saris and petticoats from her home. She buys supplies, including material, with credit from Bangalore-based Ujjivan, which started operations in 2005 as a microlender focused on the urban poor.

But Ujjivan is one of a clutch of microlenders that have made the leap from being microfinance companies, which could only extend loans, to small finance banks, offering a full array of financial services. Now, when borrowers like Nagamma come to renew their loans, they have new Ujjivan bank accounts opened for them, and can withdraw cash from biometric Ujjivan ATMs or any other ATM in India.

“Microfinance only provides loans and very small loans at that,” says Samit Ghosh, Ujjivan’s founder and managing director. “To transform lives, you have to provide multiple services that people need to survive and grow — whether it is deposits, remittances, insurance or investments.”

A graduate of Wharton business school at the University of Pennsylvania, Ghosh spent two decades as a commercial banker, mainly developing consumer banking to cater to India’s emerging middle class. But in 2004, inspired by Yunus, he left the corporate world to try to bring access to finance to working-class Indian families spurned by mainstream lenders.

“The Indian mass market — people who are lower than middle class — did not have access to any financial services,” he says. “I felt that as a financial services professional, I must give it a shot. Apart from being something socially good, this was a huge opportunity.”

From inception, Ujjivan was set up as a profit-orientated, non-banking finance company, as Ghosh too was convinced that a charity could never achieve sufficient scale to make any impact. Yet most of his initial Rs20m capital came from friends, who had no expectation of any return. “Friends and colleagues thought I was crazy, but they invested in it like a donation,” he says. “They thought it was a good cause.”

Ujjivan started with 13 branches in Bangalore, amid scepticism that the traditional group model would work, given the presumed transience of city dwellers. “Everyone was discouraging us from working with the urban poor — they said the population didn’t have social cohesion,” says Ghosh. In fact, he adds, “in urban areas there are a lot more opportunities for enterprise than in rural areas”.

Ujjivan deviated from classical microfinance practices in other ways too. Typically, microlenders want their funds to be used for income-generating activities and will only lend to self-employed women.

Ujjivan, though, lent to salaried urban workers too, even extending credit for children’s school fees or medical expenses, provided the borrower had the capacity to make repayments. The lender carried out its own rudimentary credit assessments of each borrower, rather than relying exclusively on group guarantees.

“This is somewhat of a myth, that microfinance is only for income-generating loans,” says Ghosh. He says that initially the lender attracted criticism, as it was perceived it was encouraging people to consume. “Children’s education — [is that] consumption?” he asks.

Today, Ujjivan, which listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange in 2016, has a loan book of about $1.1bn, and some 4m borrowers, spread among big cities, small towns and rural areas across 24 states in India.

Since its formal transformation into a bank in February 2017, it has converted about 120 of its 480 bare-bones microfinance offices into attractive, fully fledged bank branches, with the rest likely to switch over this year. At the latest count, 700,000 Ujjivan borrowers have bank accounts.

Ujjivan is also encouraging digital repayment of its loans, and looking to technology to enable loan renewals over the phone. “We want to incentivise [borrowers] to go completely cashless,” says Ghosh.

Small finance banks are required to have a loan book at least half of which consists of loans of less than Rs2.5m ($36,000) and to direct 75 per cent of their total credit to priority sectors such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), exports, affordable housing and education. For now, nearly 91 per cent of Ujjivan’s business still comprises tiny microfinance loans, but it hopes to reduce that proportion to half, given its new commercial focus on affordable housing loans and providing credit to SMEs.

Since raising its initial start-up capital, Ujjivan has attracted more high-profile investors, including Sequoia Capital and the International Finance Corporation.

But Sneh Thakur, Ujjivan’s head of credit and collections, says Ghosh makes clear to all his investors that the bank must not pursue profit at the expense of ethical treatment of its customers. After India’s dramatic demonetisation in November 2016, for example, Ujjivan relaxed its loan conditions, giving hard-hit borrowers more time to gather funds to make repayments.

“We cannot be only a bottom line-driven company,” says Thakur. “We are not going to drift from our vision of giving back to society.”

In Bangalore’s Gandhi Nagar district stands the premises of Fibre Flash, a family-owned business that makes religious idols, statues, Greek-style columns and other decorative items out of fibre-reinforced plastic for temples, wedding halls and homes.

Owner Sundar Raj, 60, who is still deeply involved in the production of the items, learnt his trade as a labourer before starting his own cottage industry in 2006. But the high cost of materials and slow payment cycle meant his business remained small; he and his two employees worked on the roof of his home.

Things began to improve in 2010 when his wife Indira was offered a small Ujjivan loan as part of a borrowers’ group. She gave the initial Rs5,000 to her husband, who used it to buy supplies. “I thought, they are giving money — we’ll take it,” Indira, now 58, says. “I thought it will help us grow a little, and I was relieved.”

She took out a series of loans, repaying them on time. The amounts she borrowed grew to Rs60,000 and later to Rs100,000, allowing the business to buy bigger and better equipment, increase its production and hire more workers. Her ability to bring in the much-needed working capital elevated her status within the family. “Even smaller things were discussed with her,” says her son Kiran. “Her decisions were taken very seriously after that.”

Since Ujjivan has become a bank, Sundar Raj has borrowed directly himself, taking out a Rs600,000, three-year loan. Fibre Flash now occupies a 4,000 sq ft yard, with an 600 sq ft indoor warehouse for storing finished pieces. It makes and sells about 100 items a month. And though she is no longer the direct conduit for the credit, Indira retains considerable influence over business decisions. “She is our finance minister,” her husband says. “When we needed money, she could get it.”

In 2007, Shajahan Syed used a Rs8,000 loan from Ujjivan to buy a sewing machine and escape the vagaries of her trade as a fishmonger in Bangalore, where her earnings varied sharply with the seasons. Since then, she has taken out seven, increasingly large loans, including Rs150,000 last year to expand what is now a busy garment-making workshop.

Syed now owns seven large sewing machines, including three heavy industrial machines known as over-lockers. She buys material and patterns from traders, then she and her six employees stitch the garments, which she then takes back to the traders for sale in the domestic market.

From this, Syed says she earns up to Rs7,000 a week — an income that is being used to fund the construction of her family’s new multistorey home. “We have moved up,” she says.

Vijay Kumar, 42, and his wife Devi, 32, both come from families that have traditionally worked in hand-rolling the incense sticks used in Hindu religious festivals. But since 2008, the couple have used loans from Ujjivan to expand their own Bangalore-based incense stick-making enterprise, which employs up to 12 people, especially in the autumn months before the Hindu festival season.

The loans have provided working capital that has allowed them to ramp up production. Previously, they had to use personal savings or turn to informal moneylenders, which charged usurious interest rates, to buy supplies. This meant they could make only 10kg of sticks a day.

“Previously, we didn’t have enough money to buy raw materials,” says Devi, whose first loan of Rs12,000 was part of a group. Most recently, she took out a Rs130,000 individual loan, of which Rs90,000 was invested in a machine that can makes up to 30kg of incense sticks a day.

With their business growing profitably, Devi has sent her eight-year-old daughter to a private school, and the family has bought land and is now constructing its own home, part of which will be set aside for the incense workshop, which currently is in rented premises.

Kumar says he is awed at how his wife has expanded the business. “She is the one who supervises everything,” he says. “I just do the running errands and getting supplies.”

Comments