Indigenous Australians tell their own stories in the Karrabing Film Collective

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The start of the Karrabing Film Collective’s 2016 film “Wutharr, Saltwater Dreams” hints at the universe that viewers are about to enter. Three Indigenous men are attempting to fix the outboard motor of a boat marooned near a shack. The oldest says the ancestors have broken it — they are angry because they have been neglected. An onlooker disagrees. She says the problem stems from his lack of faith in the Lord, adding that he shouldn’t believe “in old-people things”. A young man says he knows nothing about either, and seawater has eaten away the wiring.

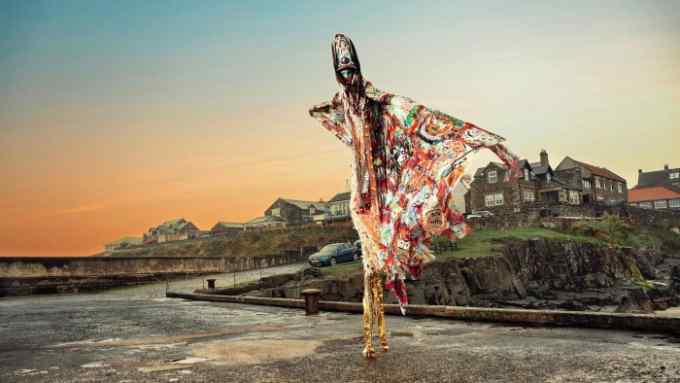

The film is intercut with dreamlike shots of water lapping on a deserted shore. A white police officer wanders through the bush — where the ancestors, represented as figures covered in pale clay designs, also live — apparently seeking the boat’s owner. The film is subtitled because the dialogue is in a local creole.

The Karrabing Film Collective is a loose group of 30 mostly Indigenous Australians based in the tiny Northern Territory settlement of Belyuen, near Darwin. It chose its name — which means “low tide turning” in Emmiyangel — to indicate that Indigenous peoples, ancestral lands and the environment are interconnected in ways not always understood by central authorities.

The collective came to international attention when one of their early works, “When the Dogs Talked” (2014), won an award at the Melbourne Film Festival and since then their films have been shown at Documenta 14, MoMA PS1 in New York and the Haus der Kunst in Munich. Their latest film, “Night Fishing with Ancestors”, is included in an exhibition of the same name at the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art in south London, which opens to coincide with the Frieze art fairs.

Angelina Lewis, a member of the collective, says it was formed in 2012 following violent clashes five years earlier over land rights which tore apart poverty-stricken Belyuen. Reporters from Australian media came to document the tensions, which left several people temporarily homeless. “That experience led us to try to find a way to tell our own stories,” Lewis says. Families help develop the stories, shooting on phones and acting the various roles. “Our community is losing its language, it is losing its ancestor stories. This is a way of keeping a spark alive,” she adds.

Karrabing’s films are a mesmerising blend of documentary and fiction, meandering between the prosaic and the mystical. The ancestors are ever-present, as are the Cox peninsula’s rugged landscapes. But so are rusting trucks, bored teenagers and cans of lager. There are undercurrents of colonial expropriation and violence.

In “Night Fishing with Ancestors”, the same actor plays an 18th-century British explorer and a contemporary mining engineer. Permission has been granted by the government for a large lithium mine close to Belyuen, Lewis says, and its metal fencing is visible in the film. “The mine stretches up to a hunting ground, it crosses wild cattle and turtle tracks, right up the saltwater coastline and fishing grounds,” Lewis says. “They promise Indigenous people jobs, they promise they won’t destroy our land. But we eat from there.”

In “Windjarrameru” (2015), police chase youths through a sacred but contaminated mangrove, incorrectly accusing them of drinking stolen alcohol. Meanwhile, poor local men collude with miners in illegal blasting to pay off small fines. Periodically the collective, who improvise their roles, break off to take a rest on the ground while shadowy figures pass secretly by.

The film obliquely references 2007’s Northern Territory National Emergency Response, or “The Intervention”, a government action to tackle the alleged abuse of children in Indigenous communities. It brought in punitive restrictions on alcohol, imposed conditions on welfare payments and partially suspended race-discrimination and land-rights acts. But the film also draws on the traditional beliefs of the collective’s ancestors.

“There’s a dual effect in their films, there’s so much you can empathise with, even laugh at,” says Natasha Hoare, the curator at Goldsmiths CCA. “But there’s another realm running alongside the mundane, one you are tantalisingly aware of but know you can’t really understand.”

Karrabing are not the only Indigenous artists catching the attention of contemporary art curators. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, opened The Land Carries our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans last month, while the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) launches an exhibition, Indigenous Histories, later in October. It is a major show of work by artists from North and South America, Oceania and Scandinavia. MASP’s artistic director, Adriano Pedrosa, will direct the next Venice Biennale in 2024 and there are expectations that he will include work by Indigenous artists.

Of course, Indigenous artists, especially from Australia, have been part of art history for some years. But Hoare says Indigenous voices are resonating more loudly in an era of climate change. “There is a sense that colonisation and environmental degradation has led to a world that is not a fit place for us all to live in,” she says. “Undoing the ills of modernity and paying attention to Indigenous forms of knowledge suddenly seems more important and timely.”

Lewis hopes that visitors to the exhibition in London will be taken on “a mysterious journey” but one they will understand. “I know we can relate to other people,” she says. “Everybody has a past. Everybody has ancestors. Everybody has a story, no matter where they come from.”

October 7-January 14, goldsmithscca.art

Comments