The Turkish tragedy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Thanksgiving is tomorrow, and Unhedged will be giving thanks for our readers, who are the reason Ethan and I get to have fun jobs. Thank you!

We’ll be back on Monday. In the meantime, we think our British readers should sign up for the FT’s excellent City Bulletin newsletter, a brisk daily primer on the London financial scene. You can sign up for it here. And as always, email us with your thoughts: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Turkey and emerging markets

Recep Tayyip Erdogan thinks that cutting interest rates will help stabilise the Turkish currency and control inflation. He is wrong. Here is the lira against the dollar since 2014, the year he became Turkey’s president (this and the following charts use data from Bloomberg):

The red circle shows the latest Turkish currency crisis, which follows the central bank cutting interest rates to 15 per cent (they were 19 per cent in September) and Erdogan making a combative speech damning global finance on Tuesday.

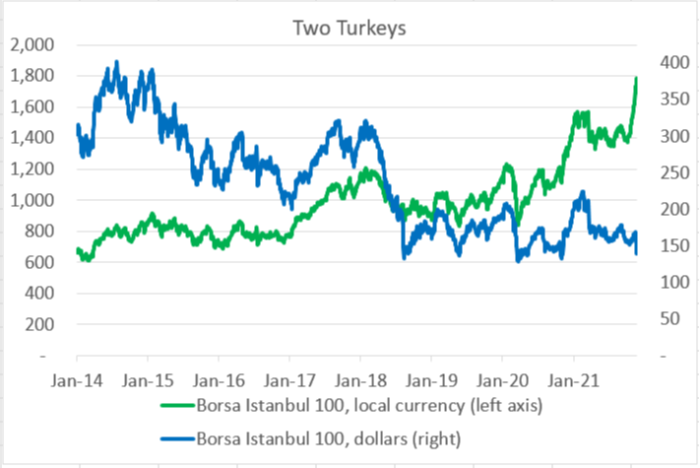

Here is how investors in Turkish shares have done, in lira and in dollars:

It’s remarkable, given the devastation of the lira, that hard currency investors have only lost half their money in Turkish stocks. But for the nation, the situation is desperate, and something will have to be done. A statement on Tuesday from the central bank suggests that the government may be intervening in currency markets to support the lira, but it does not have the reserves to do this at a meaningful scale.

Edward Glossop, emerging markets economist at Abrdn, told me that the basic options at this point are rate increases and capital controls, but that Erdogan’s belligerent tone suggests rate rises are unlikely. “Soft touch” capital controls, like requiring conversion of hard currency deposits into lira within a certain window, may be the next step. Edward Al-Hussainy of Columbia Threadneedle argues, by contrast, that rate increases are becoming more likely by the day.

The good news — for everyone except the Turks — is that the crisis has been caused primarily by bad policy that is unique to Turkey, and that there are few channels for it to spread elsewhere. As Jonas Goltermann of Capital Economics sums up, Turkish imports are not significant enough globally that their collapse would cause much external damage; foreign investment in Turkey has shrunk to become a small part of even emerging market-focused portfolios; and the Turkey mess is unlikely to make investors fear the possibility of crises in other markets, because everyone knows how uniquely bad Ankara’s policies are and how uniquely vulnerable its currency is.

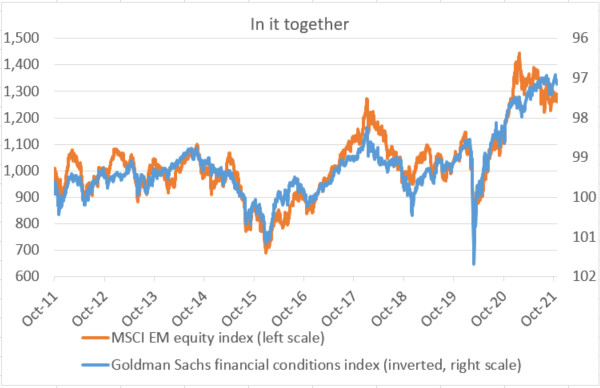

But this is not quite the whole story, because the strengthening dollar and the prospect of tightening US monetary policy are making the situation worse. In the past decade, the value of EM assets (stocks, bonds and currencies) has become increasingly sensitive to capital flows from the developed world, and therefore to the looseness of developed world financial policy. Here is 10 years of the MSCI Emerging Markets stock index, charted against the Goldman Sachs US financial conditions index, which tracks interest rates, dollar strength and stock market valuations:

That is a strong relationship. It is notable, though, that US financial conditions have loosened this year, and EM assets have not strengthened. This is down to two factors: inflation and the mess in China, which is about a third of the MSCI EM index. Here is the S&P 500, the MSCI EM index and the MSCI EM index with China struck out over the past year:

In the first half of this year, EM ex-China was outperforming US stocks; reflation, and the associated rise in commodity prices, provided a seemingly ideal environment. But in June, when inflation became truly hot, the ex-China index started tracking sideways, and in the last month, as the dollar has strengthened, US stocks have roared ahead.

Emerging market central banks can’t afford to get cute with inflation the way the US can. They have to smother it quickly with growth-killing rate rises, and outside of Turkey most have done so.

Tightening of US monetary policy is coming at a terrible time for Turkey — and a bad time for emerging markets generally. It is not surprising that EM assets are underperforming. What remains a slight puzzle, though, is the behaviour of risk assets in the developed world. They are, with the exception of a few super-speculative equities, acting as if tighter policy will do them no harm at all.

Bitcoin ETFs: a terrible product that is doing just fine, thanks

Unhedged is no fan of the bitcoin exchange traded funds. They are opaque and expensive. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s fraud concerns mean that bitcoin ETFs are really bitcoin-futures ETFs, creating heavy “rollover” costs as expiring futures contracts are sold and expensive new ones bought.

It didn’t take a genius to see this when the products made their debut, and it’s brutally obvious now. As Steve Johnson reported in the FT on Monday, only three bitcoin-futures ETFs have actually launched, compared to the dozen or so that filed with the SEC. Invesco ETF head Anna Paglia said the following after Invesco pulled it’s own bitcoin offering:

“We ran a number of simulations and the cost of rolling the futures produced a drag of 60-80 basis points [a month]. We are talking about some big numbers, 5-10 per cent annualised. It was not going to be plain vanilla replication of the [bitcoin] index.”

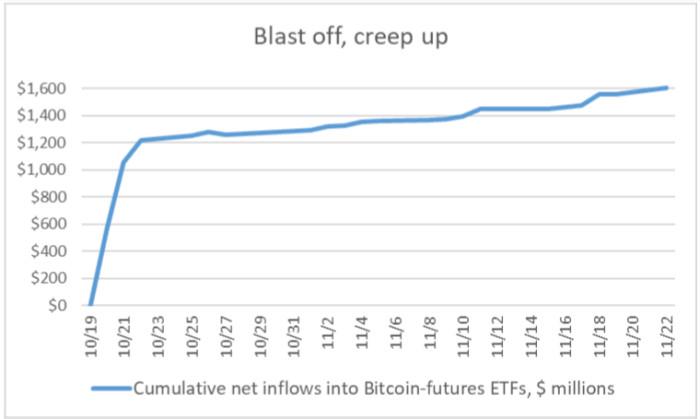

On the other hand . . . who cares? Bitcoin! Some $1.6bn has flowed into the three inaugural bitcoin ETFs — ProShares ($1.5bn), Valkyrie ($57m) and VanEck ($3m):

We asked Valkyrie chief executive Leah Wald what’s going on. She told us demand was coming from institutional and retail investors alike, but for different reasons.

For institutions, an ETF offers tax-exempt bitcoin exposure through retirement accounts, where it is impossible to hold bitcoin itself. The ETFs also help investors avoid dealing with annoying cryptocurrency exchanges or custody issues. We think this is bad — simplicity obscuring risk — but it’s logical.

Asked why retail investors shouldn’t just buy from Coinbase or Robinhood and avoid the rollover costs, Wald pointed to the costs associated with directly trading crypto, including:

Potential tax events with every purchase or sale of a cryptocurrency (tax guidance is ambiguous here);

Blockchain transaction fees;

Exchange withdrawal and transaction fees;

Custodial and/or wallet fees.

Some of these costs, according to Wald, are not transparent, and could be invisibly baked into the spread on a bitcoin trade. So savvier bitcoin investors may be reckoning that the ETF route is, in fact, more cost-effective than buying spot bitcoin.

Even if you buy that line (we’re unsure) it’s hardly an affirmative pitch — it’s just an argument that owning physical bitcoin is costly, too. The success of the bitcoin ETFs, if it is sustained, amounts to a nasty criticism of bitcoin itself (Ethan Wu).

One good read

OK, OK maybe team permanent is right about inflation.

Comments