Biden’s $16bn hole-filling project

Simply sign up to the Energy sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome to the latest edition of Energy Source. We are back in action after last week’s hiatus.

Still very much out of action is the US’s sizeable tally of “orphaned” oil wells, for which no one is responsible as they leak toxins into the environment.

President Joe Biden has a $16bn clean-up plan. But do his proposals risk papering over the cracks by throwing money at the symptoms without fixing the underlying cause? That is the topic of our first note.

Our second note picks up on more evidence that the shale sector is rising off the floor again — one of many bearish signs for oil prices.

Thanks for reading. Please get in touch at energy.source@ft.com. You can sign up for the newsletter here. — Myles

The hole in Biden’s hole-filling plan

The economist Milton Friedman disdained creating work for work’s sake.

“If all we want are jobs, we can create any number,” he said. “For example, have people dig holes and then fill them up again, or perform other useless tasks.”

Biden does not share Friedman’s reservations. The president wants to spend $16bn on a hole-filling project that he hopes could create a quarter of a million jobs.

For filling holes is essentially what the president’s plan to plug abandoned wells and restore abandoned mines comes down to: a state-sponsored work programme designed to create jobs for oil and gas workers left out of work by last year’s price collapse.

That is no bad thing. Finding work for displaced employees in the sector should be front of mind for a president with ambitions to spark a transition away from oil. Nor is it a “useless task” with jobs its only outcome. Plugging abandoned wells will stop leaks of toxic gases and liquids.

But the plan is nonetheless problematic. The current system for dealing with wells that have passed their sell-by dates is broken. And as I wrote on Sunday, unless the president’s plan actively seeks to address the underlying problem, it risks becoming a very expensive bailout for industry negligence.

The problem

The oil industry is in the business of drilling wells to extract crude. Plugging — although it only costs a fraction of the price — is generally viewed as an irritating afterthought, with no real reward. So oil companies treat the cost of doing so as a liability to be managed.

“[As] regulations improved to require companies to fully plug their wells . . . companies started doing tricks to shed those liabilities from their books,” said Clark Williams-Derry, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Companies can either leave old wells sitting idle as they use various accounting mechanisms to shrink their balance sheet value, or they can dump the wells on someone else.

This latter option means companies spin off older assets to others, who might do the same a few years later until they ultimately end up in the hands of smaller stripper well operators, which lack the means to plug them.

“Maybe they go bankrupt, they abandon their existing property and it just means there’s nobody you can go after,” said Williams-Derry. “The deep pockets have long since moved on.”

The effect of this hot potato process is that many wells ultimately get dumped on the state, which is left to take care of the clean up.

Biden’s plan to deal with these so-called “orphan” wells (for which there is no known, solvent owner) would sort out the historic backlog, much of which dates back to the early days of the oil rush in the 19th century.

But it risks furthering the problem by encouraging companies to continue to shirk their clean-up responsibilities.

The solution

Solving the underlying problem is simple, critics say: create a functioning bond system that both incentivises companies to deal with their own messes and covers the costs of doing so if the burden lands on the state.

Most states already have bond systems in place. But these tend to be woefully inadequate. So-called “blanket bonds” often allow companies to pay a fixed sum to cover all of their wells regardless of how many they are drilling. Carbon Tracker Initiative, a think-tank, reckons current industry guarantees cover just 1 per cent of the real costs of plugging wells.

“Solving the problem going forward looks something like full-cost, single well bonding,” said Robert Schuwerk, executive director at Carbon Tracker.

If companies had significant funds tied up in bonds for each well they drill, he said, they would be financially incentivised to plug those wells before any of them became a problem: “They may decide: ‘You know what, I’d rather free up that cash and go do something else with it’.”

If Biden is serious about dealing with the root cause of orphaned wells — and not just out to create temporary jobs cleaning up after companies — then he should tie his funding to an overhaul of bonding requirements by states, prioritising payments to those who get their house in order.

Academics at Columbia University point out this could delay the rollout of funds and suggest money should be given to states once they provide a road map for future system tweaks.

Whatever the timeframe, the president should avoid giving out no-strings-attached money to deal with the repercussions of a broken system without at least trying to fix that system in the process. (Myles McCormick)

The state of the oil price recovery

Twelve months ago, US crude prices were about to plunge below zero for the first time in history, triggering the sharpest downturn in the oil market in decades.

What a difference a year — and the deepest-ever Opec supply cuts — can make. Oil is trading back around $60 a barrel now, lifting the mood across the American shale patch.

Operators are optimistic — even outside the prolific shales of Texas. The Kansas City Fed’s latest survey of producers in the 10th District (including Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma and Wyoming) showed activity levels were “solid” in the first quarter and still rising, with “expectations [for] further growth in the next six months”.

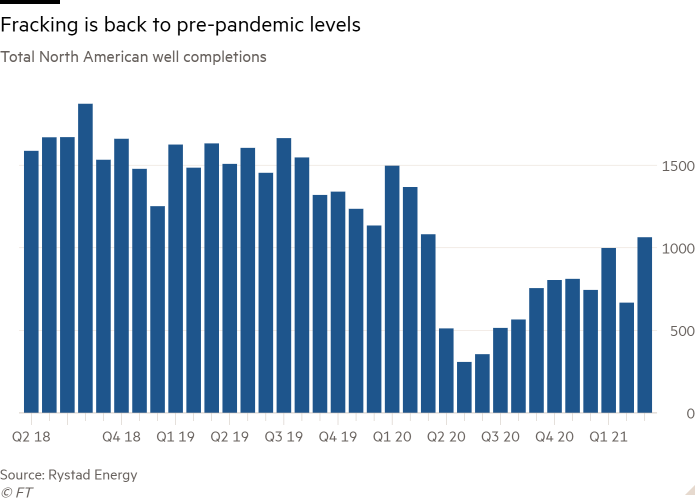

Research company Rystad Energy says fracking across North America has almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels. In the prolific Permian Basin wells of New Mexico and Texas completions in the first quarter “exceeded the required output maintenance level, so oil production is set to rise in the current quarter”, even if it moderates again after.

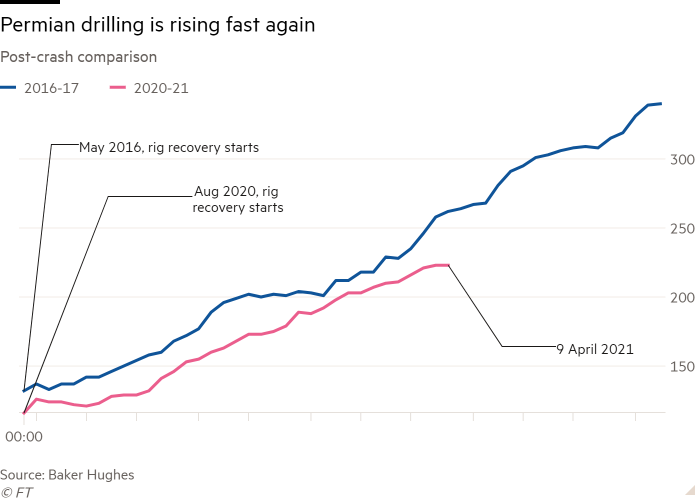

Morgan Stanley points out that rigs are rising in the Permian at the same clip as in 2016, when the drilling binge was a precursor to soaring output in 2017 and 2018.

This seems bearish, even if a US supply surge is still months away, given the time lag between a decision to drill a well and complete it.

Opec could also sap the mood. The group’s surprise decision at the start of the month to begin increasing production was a reminder of the colossal volume of supply that it could unleash, pulling down prices. Progress in nuclear talks between the US and Iran would also weigh on the market.

Morgan Stanley cited both the prospect of an Iran deal and the uptick in US drilling as it reduced its third quarter Brent price forecast, from $70 a barrel to $65-70.

What next?

Demand concerns are taking centre stage again, as coronavirus cases rise in continental Europe and parts of the US. The recovery in US petrol consumption seems to have stalled and last week was at a six-year low for this time of year, if you exclude last year’s pandemic-induced collapse.

A full global revival in oil consumption won’t come until jet fuel demand also recovers. Despite surging travel numbers within the US, the international picture remains weak, noted Bank of America, with passenger volumes down 85-90 per cent on average.

“Moreover, major economies in Asia like Japan, Australia, or India have yet to boost their vaccination efforts and will not likely attain herd immunity until 2022. Meanwhile, new Covid-19 virus strains could also complicate the reopening of international borders, suggesting that the jet demand recovery may lag other fuels,” the bank noted.

(Derek Brower)

Energy Source Live

The FT Energy Source Live event will be taking place on May 24-25 2021. Join industry CEOs, thought leaders, energy innovators, policymakers, investors and other key influencers to hear the latest thinking and insights on the future of US energy leadership and its global context. Find out more here.

Data Drill

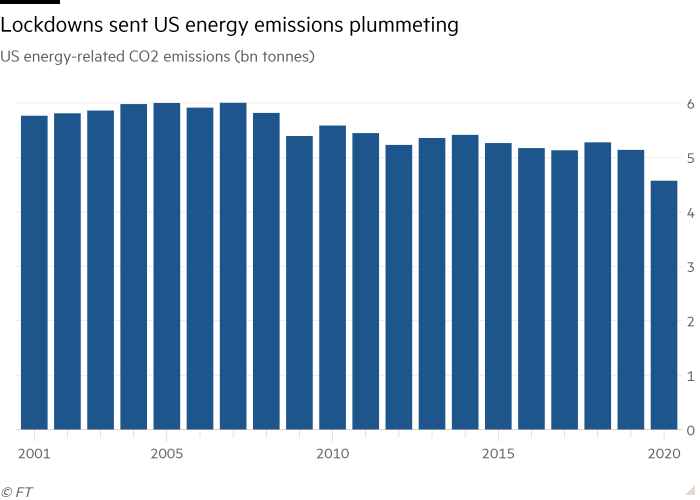

US energy-related carbon emissions fell 11 per cent last year compared with 2019 as Covid-19 restrictions slashed economic activity and kept many people at home, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The monthly emissions data show how emissions closely tracked the ebbs and flows of the outbreak. Emissions in April 2020, when economic restrictions were at their tightest, were by far the lowest recorded for a single month since the EIA’s record start in 1973. By December they were quickly moving back towards pre-outbreak levels again.

Power Points

Two South Korean conglomerates settled a dispute over allegedly stolen battery technology, clearing the way for a new battery plant in Georgia that is key to Ford and Volkswagen plans to build electric vehicles in the US.

Methane levels in the atmosphere surged by a record amount in 2020.

Mark Campanale, founder of Carbon Tracker Initiative outlined his group’s plans to create a global fossil fuel carbon registry.

The SEC is casting a sceptical eye at the ESG claims of some investment funds. (WSJ)

The global solar power-supply chain relies on materials from Xinjiang, where China is accused of genocide. (WSJ)

Energy Source is a twice-weekly energy newsletter from the Financial Times. It is written and edited by Derek Brower, Myles McCormick, Justin Jacobs and Emily Goldberg.

Comments