Lunch with the FT: Novak Djokovic

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Midway through lunch with Novak Djokovic he still hasn’t touched his food. It concerns me. I tell the world’s best tennis player that I will talk to him about my own game to give him some time to eat. It’s generally pretty wretched, I say, but it gets particularly ugly when I am 30-40 down and I have just missed my first serve, at which point I feel I am looking down into an existential black hole, sense my self-esteem ebb away, and invariably send the ball careering outside the lines. So what does it feel like for him in the “clutch” moments, which have rather more at stake?

“The first thing is to make sure you are in the moment,” he answers calmly. “That is much easier to say than to do. You have to exclude all distractions and focus only on what you are about to do. In order to get to that state of concentration, you need to have a lot of experience, and a lot of mental strength. You are not born with that. It is something you have to build by yourself.”

His conversation is fluent, intense and measured, not unlike his ground strokes. “I believe that half of any victory in a tennis match is in place before you step on to the court. If you don’t have that self-belief, then fear takes over. And then it will get too much for you to handle. It’s a fine line. The energy of those moments is so high: how are you going to use it? Are you going to let it consume you, or are you going to accept its presence and say, ‘OK, let’s work together.’ ”

It is hard to believe that this supremely self-assured champion has his scary moments. Did he ever actually feel fear on the court these days? “Absolutely. Absolutely. Everyone feels fear. I don’t trust a man who says he has no fear. But fear is like a passing cloud in the sky. After it passes, there is a clear blue sky.” Not so easy to say if you are Andy Murray, brought up under the leaden clouds of Scotland, I say, and Djokovic laughs politely.

We are in the clear blue sky of southern Europe in one of the newest models in the fleet of NetJets, a private jet company, travelling from Belgrade to Monaco, where Djokovic lives with his wife Jelena and their 11-month old son, Stefan. I have been promised a knock with him, as part of an afternoon of tennis clinics he will give at the Monte Carlo Country Club with NetJets clients. Djokovic “owns” part of the plane in which we are travelling, under the company’s fractional ownership arrangement. He tells them when he needs it; they sort out the details. It’s as simple, inclement weather permitting, as getting a restring for his racquet.

Given the demands and head-spinning rewards of the professional tennis tour, it is the only way to travel. Djokovic’s schedule is relentless: he is at the top of the game’s rankings, and holds three out of four of this year’s Grand Slam titles. He travels constantly, and needs to rest, because he doesn’t make a habit out of leaving tournaments in their early rounds.

His 10 Grand Slam career wins put him equal seventh in the all-time list, but no one seriously believes that he will stop there. At the age of 28, he is at the peak of his powers: in form, in demand, and in relentless pursuit of the two contemporary players who hold more titles than him: Rafael Nadal (14) and record-holder Roger Federer (17).

Private jetFood from Maya Bay (24 Avenue Princesse Grace, 98000 Monaco) delivered to aircraft

Mixed sashimi x 2 €88

Total €176

Djokovic has suffered — even if it is problematic to use that word when dealing with a figure of such sporting distinction — from “third man” syndrome during that time. His ascent was widely viewed as a presumptuous intrusion, upsetting tennis’s perfectly calibrated duel of archetypes: Roger Federer, the unruffled, elegant Swiss versus Rafael Nadal, the taurine Spaniard. Their battles had captured the public imagination, and sent the game spinning into unimagined levels of excellence. However could Djokovic fit in?

Well, by beating them. The Serbian has triumphed over Federer in all three of their last Grand Slam finals, while his five-set victory over Nadal at the 2012 Australian Open is widely considered to be one of the most punishing matches of all time, the tennis equivalent of boxing’s Thrilla in Manila between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. It marked a turning point: the third man was here to stay.

…

We sit down face-to-face in our leather seats, surrounded by pristine wooden panelling, and shortly after take-off, two plates of assorted sushi and sashimi are brought to us. They come from Maya Bay, Djokovic’s favourite restaurant in Monaco. I congratulate him on his US Open win in September, and ask how long it took him to pick up a racquet again after receiving the trophy.

“About 10 to 11 days,” he replies. “That is the maximum number of days that I don’t play tennis, and I needed that because I have had a very tough, competitive year behind me. I wanted to put my racquet aside, and hold my baby in my arms.” All tournaments, he says, are exhausting. “But it adds a little bit more flavour when you win,” he understates.

The last week in Belgrade has hardly been a holiday: Djokovic and his wife have been supervising the work of their charitable foundation, which is devoted to improving pre-school education in their native country. What inspired that particular mission? “Personal experience. I didn’t have that kind of schooling, because we come from a culture that believes it is better for children to stay at home with the extended family, which is not something we are against.” But education, he says, is a building block: “something that nobody can take away from you. It helps to build your character, and stimulates you to be independent.”

Djokovic may not have had the benefits of a nursery schooling but something remarkable took its place: the unfettered attentions of a coach, Jelena Gencic, who first saw him aged five, pressing against the fence of her tennis camp in the mountain resort of Kopaonik, where Djokovic’s parents ran a pizza restaurant. She asked the wide-eyed boy if he wanted to have a hit. The rest is part of the Djokovic mythology: she was so astounded by the young boy’s precocity that she sought his parents immediately, and told them he could be a star in the making.

Is it possible that Djokovic, who hadn’t picked up a racquet up to that point, could have slipped through the game’s grasp if it hadn’t been for that moment? He waves his hand dismissively. “I don’t like ‘what-ifs’,” he says firmly. “I am a strong believer that everything happens for a reason. If you ask yourself those questions, you can go on forever.”

Gencic said she would personally oversee the young boy’s development. “She saw the sparkle in my eyes. My father believed her, and he believed in me.” The coach became a mentor, introducing her charge not just to tennis but also to poetry, science and classical music. Gencic’s death during the 2013 French Open was kept from Djokovic until after his third-round match, and came as a devastating blow. “She was like my second mother,” he said in a press conference later in the week.

The teenage Djokovic stormed through the rankings. He developed a reputation for his remarkably consistent high level of play, for his athletic prowess and physical fitness, and for the odd hot-headed moment. And this year — French Open aside — he has achieved everything he wanted. I ask him how he keeps himself motivated.

“I can carry on playing at this level because I like hitting the tennis ball,” he says simply. Are there players who don’t, I ask? “Oh yes. There are people out there who don’t have the right motivation. You don’t need to talk to them. I can see it. But I don’t judge. I completely respect everybody’s freedom of choice. If it works for them . . . ”

Part of being the world’s number one is that he has become a role model, I say. He nods enthusiastically. “A lot of young people all over the world follow every move I make.” That sounds stressful. “You can look at it from both sides. Is it stressful, or is it a privilege? It gives me strength and energy. For me it is an incredible privilege.”

…

Djokovic is still only nibbling at his lunch. The sushi, as one might expect, is excellent. We drink water. No surprises: this is a man who thinks more than most about what he puts in his body, and when. Another piece of Djokovic mythology: when he was younger, he was often affected in the middle of matches by sudden medical emergencies, occasionally forcing him to pull out of games altogether. It sullied his reputation as he rose through the ranks: the usually polite Federer once called him a “joke”.

Then, in the middle of one match in Australia, he was seen on television by a doctor, Igor Cetojevic, who was no great tennis fan but who instantly managed to diagnose that Djokovic’s listlessness was a result of his diet. The men met a few months later, leading Djokovic to adopt a new diet, free from gluten, dairy products and processed sugar. The transformation in his health, and his game, was instant and radical.

“I had thought that I was eating healthily,” he says, recalling the turning point in 2010. “I didn’t eat junk food, I wasn’t drinking Coca-Cola, no alcohol.” But he concluded that gluten was the culprit. “I thought about it and realised I had eaten it every single day. It is in our culture, that we eat bread with everything. So I had over-consumed it a lot.”

He lost four kilos in a very short time (“which is a lot for a professional athlete”) and was warned that he risked losing energy. Instead of which, he says, “I felt better than I had ever done before: more alert, more aware, more energetic.” This was bad news for the rest of the tennis circuit, who were suddenly confronted by a revivified opponent with superhuman levels of endurance. Since the turnround, Djokovic has contested 16 of the last 21 Grand Slam finals.

He says his new habits do not constitute a “diet”, rather a new approach to nutrition. “I try to respect everything I put on my plate,” he says. Two years ago, he wrote a book, Serve to Win, a combination of biography, recipe book and self-help manual. Food has become an important hobby for him and his wife. “Nowadays, about 50 per cent of what I eat is raw.” He picks up another piece of sashimi as if to emphasise the point.

…

Now here is the problem for us tennis fans, I tell him. We have been spoilt by a golden era. The bar has been set so high by Djokovic and his immediate rivals that we fear a comedown. Where are the future stars of the game, and can they possibly live up to those standards?

“Before the last two years, it was worrying for the tennis world,” he concedes. “The young players were showing potential, but they weren’t coming up. People love Roger, as they do Rafa, but their day will come, as will mine. But in the last two years I think we have seen a lot of future stars. [Borna] Coric, [Nick] Kyrgios . . . ” Ah, wait a minute, I interrupt. He was a little bit of a naughty one, wasn’t he? (The Australian was roundly condemned and fined for making lewd, sledging remarks about Stan Wawrinka’s girlfriend at the US Open.)

“Well, he is, but, actually, deep inside, I think he is a very good guy. He has a little bit of an identity crisis, I think. He is still trying to establish himself. I spoke to him in New York. I said, ‘Listen, I know everyone criticised you, and I was one of them,’ and I was happy to tell him that face-to-face. But I wanted to add that I suffered similar things, maybe not to that extent, and it is a very valuable experience. I said, ‘If you ever want to talk to me, I am here and I am willing to help you.’ I practise with him, and I talk to him, and he is a good guy, and really, really talented.”

We begin our descent. I say that last year I saw his picture on a fresco in the Republika Srpska town of Andricgrad, a massive construction project conceived by the film director Emir Kusturica, with whom Djokovic is friendly. I ask him what it was like to be a rising sports star, with strong patriotic feelings, in the 1990s, in the middle of the wars in Yugoslavia, when those very feelings were being condemned in the wider world.

“It was one of the toughest times in the history of the Serbian people,” he replies. “There were lines of people queueing for bread every day. In 1999 during the Nato bombings our lives were in danger every day. They killed many innocent people for no reason.”

Those events “helped me to become the person I am today. They made me mentally stronger. They made me hungry for success. They stay inside your heart, always. You can’t forget them. The only way is to move on, forgive, use that experience as a positive reinforcement.” He returns to the subject of fear. “If you can channel it in the right way, fear will turn to strength.”

The plane lands, and we part ways. Later in the afternoon, I watch Djokovic as he arrives at the club in Monaco. He is unfailingly polite, and charms his audience. Adults and children alike pose for selfies. He is in role-model mode, playing the part to perfection. The thought occurs to me that, rather than go down in history as the third man, he may actually transcend the archetypal qualities of both of his rivals: even more gracious than Federer, still steelier than Nadal.

At one point he approaches the extravagantly laden refreshment table, picks up a 2 sq cm fragment of pizza, and pops it into his mouth. I turn to Greg Rusedski, a former British player, who is master of ceremonies for the event. “Don’t pizzas have gluten in them?” I ask mischievously. Rusedski replies with a broad smile. “Sometimes I think you’ve got to let go a bit,” he says. Such wild behaviour is not unprecedented: Djokovic celebrated his Australian Open win in 2012 with a single square of chocolate.

The time comes for our knock. I am in a long line of NetJets clients. We will each get one to two minutes each. There is an audience of about 200 people, sipping champagne, and watching us more carefully than I was hoping. It comes to my turn, and I am trying to turn fear into strength. We have a gentle rally, which he allows me to “win” by not moving towards the ball at all. In a blatant piece of gamesmanship, he says he likes my “game face”. I regain my composure, ratchet up the intensity, and shorten the next rally with a rasping volley which goes exactly where I meant it to, somewhat to my surprise. There is a ripple of applause. It is one of the most dreamlike moments of my life.

He comes to the net to shake hands. “In the moment!” I say to him. “In the moment!” he replies, laughing, and turns briskly back to the baseline to face his next opponent.

Peter Aspden is the FT’s arts writer

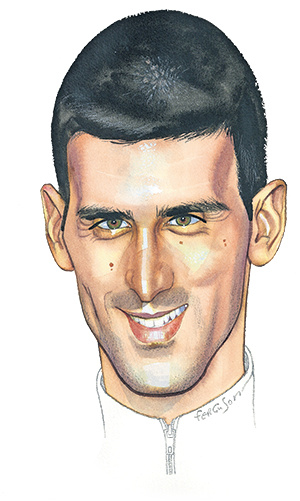

Illustration by James Ferguson

Correction: Andricgrad is in Republika Srpska, Bosnia’s Serb-dominated entity, and not in Serbia, as originally stated.

Comments