Inventions still need a human touch

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The inventor’s name under an application to the European Patent Office reads as ‘Dabus’. But Dabus is not human. It is a machine. And by applying for a patent in its name, Dabus’s owner was attempting to change the very foundations of intellectual property law. He failed. For now.

Dabus had invented a flashing light that uniquely draws the eye in emergency situations, claimed University of Surrey law professor Ryan Abbott and Dabus’s creator, Missouri-based inventor Stephen Thaler.

The pair lodged their patent claims with the EPO, UK Intellectual Property Office and the US Patent and Trademark Office. All three gatekeepers, while seemingly agreeing the invention was unique enough to warrant a patent, rejected the applications in recent months on the grounds that only real-live humans can be inventors. Mr Thaler is appealing the EPO’s rejection of his patent.

Not even companies — which as legal entities can own patents — can be deemed the inventor of a thing. Under current laws in most major jurisdictions, only humans can be inventors. Put simply, things cannot invent other things.

There is a reason for that, says Alexander Korenberg, a patent attorney and partner at Kilburn & Strode in London. Patent laws are designed to protect and encourage innovation. Since machines inventing other things was not even a theme of science fiction when patent law began, Mr Korenberg says patent law assumes that an invention starts with a person coming up with “an inventive concept” — the spark that makes an invention.

“As the recent Dabus cases have shown, at least the USPTO, EPO and UKIPO think that inventions can only be made by people — that only people can be inventors,” says Mr Korenberg.

Prof Abbott and Mr Thaler are challenging that premise, however, arguing that the denial of the creative potential of machines risks dampening innovation and investment in artificial intelligence.

“Machines might not be incentivised by patent ownership but the people who invent machines are,” says Prof Abbott. “Machines are going to be a significant source of invention in the future, and you want to have the right system in place to promote that sort of activity.”

Many lawyers are not persuaded about Dabus’s legitimacy as a genuinely independent inventor, but nonetheless agree patent offices have to confront the question of creative machines for the very same reason why corporations cannot be inventors — the protection of innovation.

“If you have an invention that was completely conceived by AI — and not by a human person — you assume a risk by putting a person’s name on the application as the inventor. They weren’t the one who conceived of the invention,” says Tina Yin Sowatzke, a lawyer at McKee, Voorhees & Sease, an intellectual property boutique firm in Des Moines, Iowa.

“The purpose of providing patent rights is to promote the sciences and useful arts, and to provide people with an incentive to create innovations and invest time and resources into developing innovations to better our global society.”

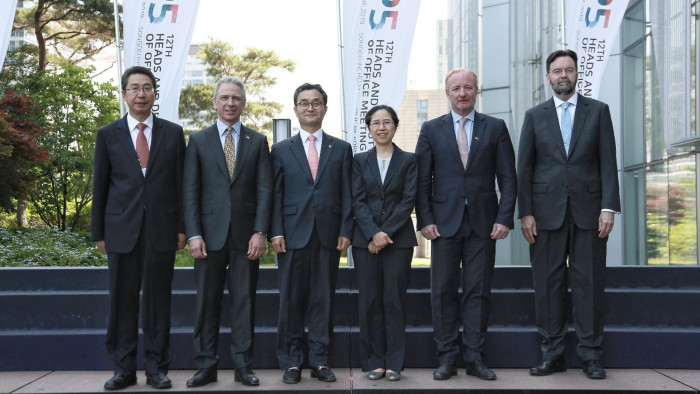

While the Dabus applications were denied, their filing has prompted the world’s five biggest patent offices — China, Europe, Japan, South Korea and the US — to form a joint task force to investigate the impact of new technologies and AI on patents. The task force’s first meeting was in Berlin mid-January.

Geert Glas, a Brussels-based IP lawyer at Allen & Overy, says not addressing AI as a potential inventor risks patent law falling behind economic and scientific reality. He argues that if an AI system can truly invent something, then the person behind that system could not — under the current rules — legally own a valid patent for the AI system’s invention. While such persons may own or have programmed the machine that did the inventing, they did not substantially contribute to the invention created by the machine. As a result, they cannot then put their name on the patent application as the inventor. “All of a sudden you can see the validity of many AI-based patents coming into question.”

The use of AI in research, innovation and business has become increasingly important as the technology advances, agrees Pieter Nel, an expert in the field. But to say AI systems have advanced to the point where machines are inventors is fanciful, he believes.

“Artificially intelligent machines and algorithms are tools, not sentient individuals — and they won’t be sentient any time soon,” says Mr Nel, chief technology offer at fintech company Ocrolus, which uses AI to simplify form processing for banks and other financial institutions.

Mr Nel thinks the debate over AI systems owning patents is a distraction and a fool’s errand.

“People won’t stop innovating just because an AI algorithm can’t own a patent. We are a long way from human-level intelligent machines but we’re not a long way from AI innovation that helps society in significant ways,” says Mr Nel. He argues the debate over AI patent ownership is “an intellectually stimulating idea with little current real-world value”, adding: “Patent offices are going to have to decide what purpose ascribing rights to a machine serves — and they may find that ultimately it is very little.”

Mr Korenberg argues patent law at present needs a person to be the inventor “for protection to exist”.

On this basis, if a machine came up with an inventive concept independent from human input, “then under present laws in at least Europe and the US, you would have an invention that nobody can own, because it cannot be protected by patent law”. In which case, he argues, “IP policy may need to catch up with technological reality if investment into ‘artificial inventions’ is to be encouraged”.

For his part, Mr Thaler — Dabus’s inventor — says he truly believes his creation is aware enough to be a legitimate inventor.

“I would claim Dabus has feelings,” he says. “They’re not human feelings — machines have not held their firstborn, seen the sun rise or had a drink at sunset — but nevertheless it’s the formation of a series of memories. You see something or imagine something, and these chains become a sequence of memories. That’s the essence of sentience.”

Comments