Leaked CIA cyber tricks may make us WannaCry some more

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

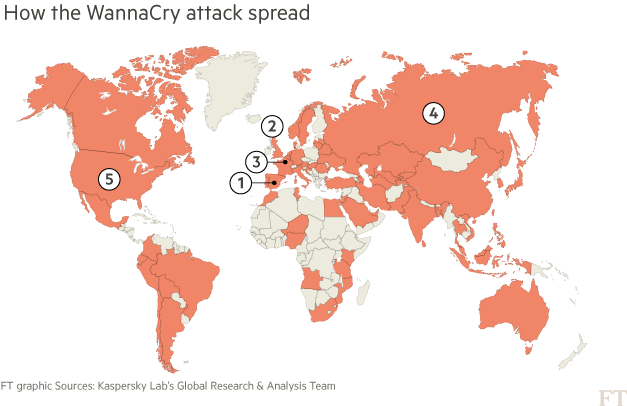

In early May, within a narrow 24-hour window, the spread of WannaCry — a semi-autonomous piece of criminal software designed to encrypt victims’ hard drives and demand payment to unlock them again — became one of the most virulent cyber attacks in the history of the internet.

It spread across the world, knocking out a third of the UK’s National Health Service and shutting down 1,000 computers in Russia’s ministry of the interior. It was indiscriminate, disrupting universities and petrol stations in China, and incapacitating key-systems at multinational businesses.

It soon became evident to cyber security analysts dissecting WannaCry’s code that the key to its voracious spread was a cyber weapon engineered by the US government: EternalBlue.

The incident has highlighted the threat from a sprawling underworld of digital cyber criminals that has ballooned in recent years. Europol, the EU crime-fighting agency based in The Hague, estimates that more money is now made illicitly from cyber crime than from the international narcotics trade. In an age of leaks, proliferation and digital anonymity, WannaCry has also put a spotlight on governments and their offensive cyber weaponry capabilities.

EternalBlue is just one of dozens of “exploits” — programs designed to take advantage of unknown loopholes in commonly-used software — that the US National Security Agency has stockpiled over the years.

The NSA is far from alone in such endeavours. Allies and adversaries are racing to find and use exploits of their own, as cyber space rapidly becomes the frontline of global geopolitics.

The most valuable of such exploits are known as “zero-days”, so-called because they are based on weaknesses in software that are completely unknown, giving targeted organisations zero days in which to protect themselves.

For the most part, such exploits are valuable as a means of espionage because they offer ways to hack into systems without detection. But these tools can often be repurposed with ease. On the dark web — the parts of the internet that are not reachable through regular search engines and often require specialist knowledge to access — there is a thriving trade in exploits, and a community of hackers, criminals and activists that develop and repurpose them for malign ends.

EternalBlue is just one of a trove of high-grade exploits that in recent months have been stolen from the US government and which can now be found online. Some have emanated from WikiLeaks, the whistleblowing site, which is gradually releasing what it calls “vault 7”, a cache of CIA cyber tools, so that tech companies can patch the software flaws these target. An even greater number may be in the hands of an anonymous group western intelligence officials believe is a front for Russian spy agencies, known as the ShadowBrokers.

“WannaCry is just the latest in a series of events that should have been wake-up calls over this problem,” says Toni Gidwani, director of research operations at the Washington-based cyber intelligence firm ThreatConnect. “The characteristics of the attack and how quickly it spread were a progression . . . they showed how we have seen the cyber crime environment evolve. Groups have become more sophisticated, and they are adapting more and more tools. When you have vulnerabilities leaked like those by the ShadowBrokers — when things like that become public knowledge — you very quickly see weaponisation.”

She adds: “We are going to see more of this for sure.”

Worms, exploits and angels: online dangers you need to be aware of

Stuxnet

The Stuxnet worm is widely regarded as one of the first cyberweapons. It was developed by US and Israeli government agencies to disrupt Iran’s nuclear programme, by interfering with the specialist computer programs that guided uranium-refining facilities. Exactly when it was developed is unknown. The first sample was identified publicly in 2010, however. Stuxnet had somehow escaped from the Iranian facilities it was targeted against and had begun to spread across the internet accidentally infecting similar industrial systems. In 2012, cyber analysts warned that design features from Stuxnet had begun to creep into criminal malware that they were monitoring. Stuxnet’s pioneering technique of using stolen digital security certificates — digital passports that allow information to be exchanged securely over the internet — to mask its activity is now widespread among all forms of malware.

HackingTeam

In 2015, HackingTeam, an Italian private company that developed and sold hacking tools to governments, was itself hacked. Many of its exploits were leaked online. They included a zero-day vulnerability that exploited Adobe Flash. This allowed the exploit’s users to install malicious code on any targeted computer. Almost all browsers, from Safari to Chrome, which use Flash, were vulnerable as a result. “Very soon after those leaks we saw multiple Chinese groups picking [the exploits] up and begin using them right away,” says Steve Stone, global intelligence lead at IBM’s X-Force incident response and intelligence service.

Weeping Angel

In March 2017, WikiLeaks published the first documents in what it said was a huge cache of CIA exploits. The most eye-catching was codenamed “Weeping Angel”. It exploited loopholes in the software running Samsung smart TVs that enabled its operators to turn those TVs into listening devices and spy on their watchers. Other CIA exploits showcased a range of weaknesses in internet-connected devices. Security analysts believe the “internet of things” — the connecting of everyday objects to the internet — will be one of the next big targets for cyber criminals, and the CIA’s exploits will be invaluable to them. Already cyber criminals have used such exploits to begin turning thousands of devices, such as digital cameras, into “zombie” computer networks or “botnets” they can use to attack and cripple specifically chosen target networks or websites by bombarding them with information requests.

EternalBlue

The ShadowBrokers dumped EternalBlue and a number of other NSA exploits on the internet in April 2017. Less than a month later, WannaCry was born. EternalBlue exploits a loophole in Windows systems file sharing protocols — which provide access to files and directory services on a network. In systems where these are set up — such as with drop boxes or shared folders — the exploit allows attackers to move seamlessly from machine to machine, implanting code without detection. EternalBlue was far from the only dangerous exploit in the set. Another, EsteemAudit, has also been repurposed by hackers on the dark web. It exploits a weakness in computers’ remote desktop protocols — the code that allow users to grant remote access to IT administrators or colleagues to their desktop machines.

Athena

Recent weeks have seen yet more US government cyber weapons leak. WikiLeaks published details of “Athena” on May 21. The whistleblowing site has been releasing a new CIA exploit every week since Weeping Angel. Athena is a particularly powerful hacking framework developed for the CIA to target and exploit Windows systems. It is capable of breaking into all current Windows operating systems, from XP to Windows 10. For criminal groups, such a platform has huge potential.

———————

1. On Friday May 12 2017, mobile operator Telefónica was among the first large organisations to report infection by WannaCry

2. By late morning, hospitals and clinics across the UK began reporting problems to the national cyber incident response centre

3. In Europe, French carmaker Renault was hit; in Germany, Deutsche Bahn became another high-profile victim

4. In Russia, the ministry of the interior, mobile phone provider MegaFon, and Sberbank became infected.

5. Although WannaCry’s spread had already been checked, the US was not entirely spared, with FedEx being the highest-profile victim

———————

Comments