J Crew, Brooks Brothers and the decline of American prep style

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On May 4, J Crew, the 73-year-old retailer whose fashion-forward take on prep captured the American style zeitgeist in the mid-2000s, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Virginia, becoming the first significant fashion casualty of the Covid-19 pandemic. Brooks Brothers, another institution of New England prep style, has hired financial advisers to explore its options. It is $600m in debt.

Such a state of affairs would have been difficult to imagine when I enrolled in a small liberal arts university in New Hampshire 15 years ago, where students lounged on the green lawns of their fraternity houses in J Crew madras shorts and popped the collars of their Lacoste polos only semi-ironically.

Or when I lived, briefly, in Washington DC, in 2009. The city was a J Crew catalogue in motion — you could hardly turn a corner without seeing the brand’s No 2 pencil skirt, “Bubble” necklace or elasticated leather ballet flats. Brooks Brothers, though considered a bit old-fashion, remained a dependable supplier of suits and shirts to young graduates embarking on careers at investment banks or on Capitol Hill.

That J Crew was struggling prior to the pandemic was no secret. After a spectacular turnround from 2003 to 2015 under former Gap chief executive Mickey Drexler and longtime J Crew designer Jenna Lyons, the company’s sales had slumped, leading to a succession of management changes and making it difficult to pay off the $1.7bn in debt it had acquired in a 2011 private-equity buyout. The J Crew Group had been planning a March initial public offering for Madewell, the younger, smaller and better-performing sister brand of J Crew, to pay off a debt maturity due next year. When the pandemic hit, those plans were scrapped.

For a brief period, J Crew defined the spirit of American fashion. The brand’s jewel-toned cashmere sweaters, cheap-but-chic statement necklaces and slim chinos were just the thing for young and mid-career office workers who were adapting to an increasingly casual workplace and wanted to build a professional wardrobe that wasn’t black, beige and boring. It was preppy yet democratic, functional but also fashion-forward; it was worn by lawyers and students, endorsed by Vogue and first lady Michelle Obama.

Creative director Lyons became a style celebrity, the brand an imitation of her eclectic way of dressing: ripped white jeans with a black stiletto, a sequinned blazer with a crisp white shirt and cargo pants. Nearly all of it was available online or at a local mall for $200 or less.

In 2015, J Crew’s decade-long sales climb took a sudden turn. On a call with investors, Drexler blamed specific style misses such as the ill-fitting “Tilly” jumper, but vocal J Crew loyalists accused the brand of lowering its quality standards and pandering too much to a fashion customer.

Abra Belke, a former Washington lobbyist who runs the influential Capitol Hill Style blog, was one of those loyalists. “When I started the blog in 2008, 70 per cent of my wardrobe was J Crew. That was true of most female Hill staff at the time,” she recalls. “It was a place where you could find business suits and cardigans, pieces that were still cute but appropriate for work.”

By 2011, she noticed the quality was starting to slip. “I’d spend $80 or $90 on a sweater and it would pill the second time I wore it. The linings were cheap fabrics that would pucker. It was the first time I would order clothing and think, ‘This isn’t worth what I paid for it.’” By 2014, she was getting so many complaints from readers about poor fabrics and weak seams that she largely stopped featuring the brand on the blog.

Belke thought J Crew was losing track of its customer. There was too much neon; sequins were splashed on everything. “I remember on the main page of the suiting section, there was a model wearing a pencil skirt and a suit jacket and a sparkly top underneath a baseball T-shirt. And I was like, that’s not a look for the office, it’s just not,” she says. “[J Crew] tried to sit at the cool girl table and it didn’t work out.”

In 2017, J Crew parted ways with Lyons and men’s designer Frank Muytjens, and Drexler stepped down as CEO (he stayed on as chairman until 2019). The assortment became more basic, and boring; fewer new designs were introduced. “I still pop in the store now and then, try on a dress, and it’s literally the same exact cut [as years ago],” says Alina Damas, a 22-year-old student at Harvard. “It’s the same with shoes. You can’t keep selling the same flats in different [shades] of cognac and think people won’t realise.”

If J Crew’s makeover had gone a few sequins too far, Brooks Brothers’ has been too late in coming. The brand that has dressed presidents from John F Kennedy to Donald Trump has laid claim to many “firsts” in its 202-year history: the first ready-made suit (1849), foulard tie (1890), madras print (1902), wash-and-wear shirt (1953).

But the innovations have dried up. Under chief executive Claudio Del Vecchio, billionaire son of eyewear maker Luxottica’s founder, who acquired the brand from Marks and Spencer in 2001, the clothes and stores have become old-fashioned, and its customer aged. The edgier customer it brought in via Thom Browne’s Black Fleece line in 2007 departed when Browne did, in 2015. By the time Del Vecchio got around to hiring designer Zac Posen to refresh its women’s line in 2014, demand for dressy workwear was fading. The customer had also moved online.

Today, in Washington, “the whole city is wearing Everlane”, says Belke. “That’s the look now — not quite hipster, but certainly more modern than the preppy American sportswear look for five, six years there.” The direct-to-consumer brand’s cashmere crewneck jumpers, wide-leg crops and ballet flats are the new women’s uniform on Capitol Hill. It’s not just its aesthetics that resonate; its values around transparency and sustainability do, too.

Neither J Crew nor Brooks Brothers is likely to disappear. The former filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which will allow it to restructure (rather than Chapter 7, which would have meant liquidation). But on the other side — of bankruptcy, of the pandemic — will America want what these two brands have to offer?

Certainly their current strategy — a return to core styles marketed via nostalgia — won’t be the ticket. Too many other brands do navy blazers and Oxford shirts, and for a lower price. And if they want to court a younger customer, they’ll need to stop peddling the same images of American aristocracy they did 30 years ago. The pictures that populate their Instagram feeds — of smiling blondes strolling through ivy-clad colleges or gazing at the horizon from sailing yachts — feel white, privileged and out of touch.

“I think there is a backlash against things that are associated with the 1 per cent among younger people, and that kind of classic, Hamptons, Montauk, striped tee, white jeans, cashmere cardigan look which is associated with a kind of income price point,” says Belke.

“For the younger generation, prep style is associated with a very conservative view of the world . . . it’s not something that speaks at all to their values,” says Neil Saunders, managing director and retail analyst at GlobalData Retail. It hasn’t helped that beige chinos, like “Make America Great Again” hats, have become part of the Trump supporter uniform. “Prep is very conformist, and it’s also about exclusivity — I’m a member of the club and you’re not.”

Teens today prize individual style, comfort and sustainability. They care more about political and social issues than previous generations, and gravitate towards brands that they feel share their values. In a twice yearly survey of US teens’ spending habits, investment bank Piper Sandler (formerly known as Piper Jaffray) noted that the likes of Ralph Lauren, Sperry and Vineyard Vines have been steadily ceding market share to athletic brands such as Nike and Lululemon. Nike’s 2018 campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick, the NFL player who famously protested racial inequality by refusing to stand during the national anthem, was a huge hit.

It’s unlikely that Brooks Brothers or J Crew will be able to dictate mass tastes the way they once did. Mainstream styles circulate much more quickly than in earlier decades; clothes are cheaper and more quickly disposed of, and there is no longer one predominant style. On a broader level, fashion has become more casual and sportier — today, Canada Goose parkas and leggings are the dominant campus uniform.

“I think streetwear has completely taken the role that the preppy brands used to have,” says Arman Badrei, a 20-year-old student at Princeton. Brands including Supreme, Fear of God and Moncler have become more of a status symbol than the “classic gentleman” look made popular by J Crew and Brooks Brothers, he says.

Light after the lockdown

FT editors look at how the coronavirus crisis will transform the creative industries — from fashion to arts

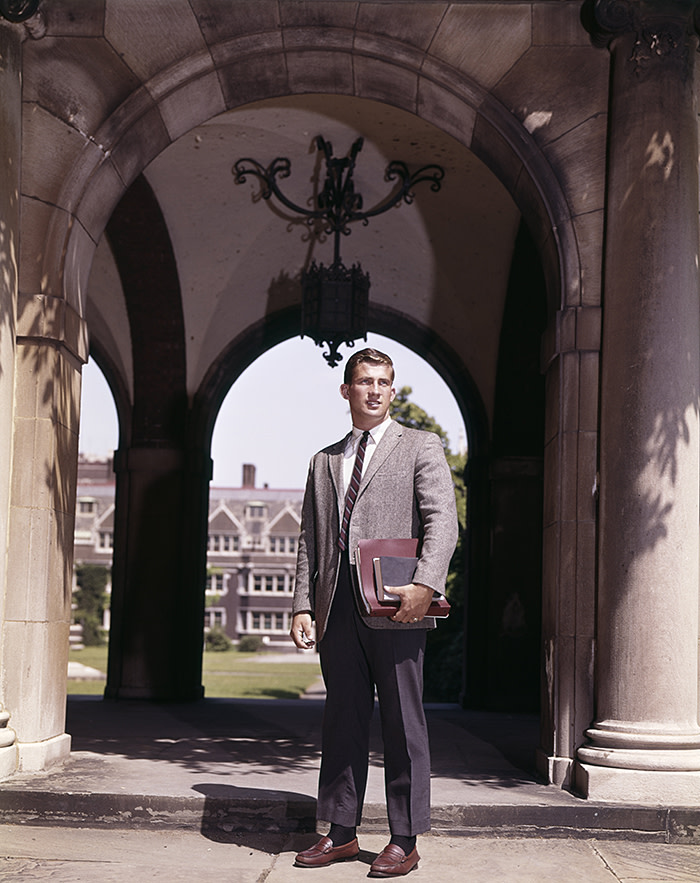

Yet there remains something very compelling about that classic look. Recently, I flipped through a copy of Take Ivy, Japan’s 1965 ode to the dress and manners of students at elite New England universities. To my eye, the sturdy wool jumpers, tailored chinos and loafers look as good now as they must have 55 years ago. In contrast to today’s styles, they are classic, well made and well fitted. Besides the ubiquitous varsity jacket, there is very little that is oversized.

What purveyors of prep might need, then, is not so much a shift in aesthetics — though some of that is needed — but a shift in values. Increasingly conscious of the ills of fast fashion, consumers are looking for what prep style has long offered: timeless, good-quality, easily interchangeable clothes that can be worn for decades.

There is already some evidence that prep style is on the way back: the men’s Spring/Summer 2020 catwalk collections were awash with prep staples such as knitted polos, tassel loafers and pleated trousers cut high on the waist.

“There is no question in my mind that preppy dressing is back,” says Teo van den Broeke, style and grooming editor of British GQ. “There’s something about the smarts-meets-sports easiness of preppy dressing that feels ultra-relevant right now.”

Letter in response to this article:

Teenagers will eventually be drawn to classic styles / From Peter D Hahn, London W9, UK

Follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Comments