‘We will rebuild everything’: war, loss and faith in Ukraine

Simply sign up to the War in Ukraine myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Early February 2022. In the city of M in the south of Ukraine, the threat is palpable — it looks like Russia will escalate the hybrid war, which is in its eighth year already. It is probable that the Russian occupiers will try to cut through the Donbas-Crimea land corridor and seize new territories. And it will definitely happen here.

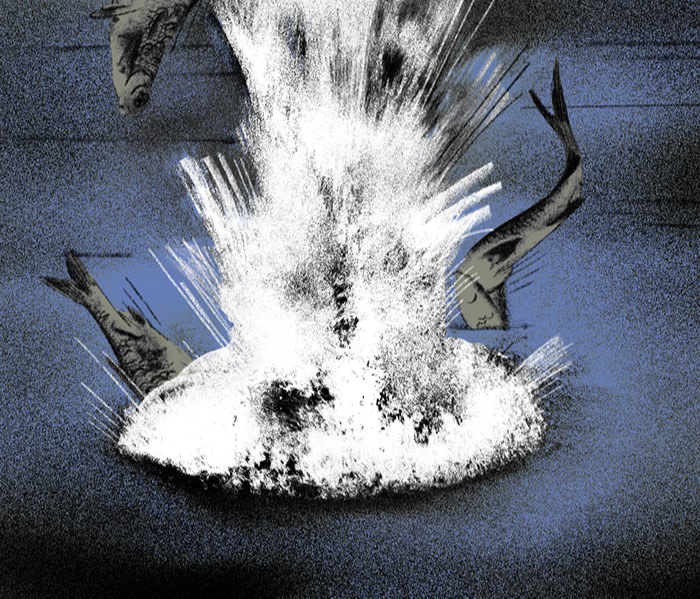

V and his wife N, both 44, are scientists who have devoted their entire lives to the study of fish. They decide, just in case, to pack an emergency suitcase, and now, every morning when they go to work, they take documents, laptops and their savings with them.

They decide to send V’s 70-year-old mother to Kyiv. Their 19-year-old son also lives in the capital. At least he and his grandmother will be safe. After all, if Russia attacks, it will never dare to strike Kyiv. This would be madness, a destructive anachronism that is impossible to imagine.

V and N devise a plan of where, if necessary, they will have to evacuate to. It is two weeks before the invasion.

As I am writing this essay, the 10th month of the full-scale war with Russia is passing and the bloody year of 2022 is coming to an end. Since the invasion, I have answered the question “How are you?” hundreds of times. And dozens of times I have been asked: “How did the war change your life?” When people ask something, they expect to hear words. I can only howl and try to hide this howl behind a smile.

So when people ask me, “How did the Russian full-scale invasion change the lives of Ukrainians?”, I tell them the story of V and his wife N. I cannot give their real names, given the fact that Russia still exists.

February 24. V and N’s house is not far from the military airport. The couple wake up to the sound of rockets. N says the words that at that moment resounded throughout the country: “It has begun.” V goes out on to the porch and sees five rockets cutting through the sky and flying towards the airport.

The occupying forces are advancing rapidly. Ten hours after the start of the invasion, they are already 100 kilometres from the city of M.

V calls his son in Kyiv, who says that Russian rockets hit the capital as well.

An hour later, N unties their four-year-old shepherd dog, which they affectionately call Ice Cream, asks their neighbours to look after it and gives them the house keys. Deep in their souls, they believe that they will return in a few days.

V and N get into the car. All they have are the essentials: the things they are used to having with them at all times — documents, laptops and savings. One last look in the rear-view mirror. In addition to the beloved house, built with their own hands, it reflects something that cannot be seen in an ordinary mirror — normal life, dozens of research expeditions to the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, a happy childhood and youth in the city of M, which in recent years has become better developed and equipped for a comfortable life. With the ice rink, new hospitals, parks, illuminated roads, you couldn’t imagine this place in ruins. They are leaving behind two businesses. One is to do with ecological management; the other is a tourist attraction in which they planned next year to open the “Museum of Berries”, a place where you could sample every type of berry there is.

The mirror at times shows the future, which used to be so clear but is now completely obscured by the fog of war.

V and N leave for Zaporizhzhia. The next day they will be reunited with their son. And the occupying Russian troops will enter the city of M.

As I am writing this essay, an explosion occurs in Madrid — an envelope sent from an unknown address explodes in the hands of an employee at the Ukrainian embassy. Envelopes with explosive devices are also received by a company that produces weapons for Ukraine, the Spanish prime minister’s office, the Spanish defence ministry, the Torrejón de Ardoz Air Base and the US embassy in Madrid.

Three days later, the Ukrainian embassies in Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Croatia and Italy report receiving bloodstained packages containing gouged animal eyes.

According to Dmytro Kuleba, Ukraine’s foreign minister, Ukrainian embassies have received a total of 31 such letters in 15 countries — with explosives or eyes.

At present it is not known who is behind the parcels. It is known only that this all resembles a badly staged cosplay of “The Godfather”. In the same spirit, a European parliament proposal last month to designate the Russian private military company Wagner a terrorist organisation was followed by a widely circulated video of one of the group’s associates presenting a violin case containing a sledgehammer smeared with fake blood.

While studying at university, V was faced with a choice — what to research: birds, amphibians or fish? V and a fellow student were sitting in a dormitory trying to determine their future. Finally, V’s friend said: “Let’s do fish. At least they do not talk. Everything else either bites or yaps.”

V has had a brilliant academic career. Ten years ago, at 34, he became a doctor of biological sciences — a young age for a Ukrainian scientist to obtain the highest scientific degree. His works are cited. He never thought that he would end up in the army.

V and his family come to Chernivtsi to stay with a friend, also a professor, an ichthyologist who the day before had volunteered for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The first week of the full-scale invasion passes. Like tens of thousands of men and women across the country, V joins the Armed Forces and becomes an ordinary soldier. His new position, occupation and assignment is “driver”.

V finds himself in a military unit based on the site of an educational institution. He is settled in barracks converted from a student dormitory. Teachers become soldiers. A new reality begins, in which he and I finally cross paths.

As I am writing this essay, news continues to come from liberated Kherson. More and more evidence is illuminating exactly what the Russian occupation authorities have been doing under the slogan: “Russia is here for ever.” According to the Ukrainian authorities, the Russians set up at least 11 places where people were imprisoned, four of which were equipped for torture; approximately 600 people were being held in these torture chambers at any one time and thousands of people passed through.

For four days, Russians stripped the Kherson Art Museum. According to the museum’s administration, more than 60 people loaded the paintings on to trucks and sent them to Crimea. The Russians stole everything: ancient coins, gold jewellery, Greek amphorae, works by western artists and Ukrainian and Russian artists of the 18th and 19th centuries and Soviet times. The works of contemporary artists they left.

This has happened before. In 2014 in occupied Donetsk, Russian-backed separatists turned the Izolyatsia art centre into a prison, and art objects were used as practice targets for shooting. Russia is a country that is terrified of becoming “modern” or “contemporary”. It is a country that lives by archaisms, in the holy conviction that it will exist for ever.

One of those imprisoned by the Russian occupiers says that they were held without getting any news. And he survived only on prayers for Ukraine to be given weapons, and prayers for the Ukrainian military.

In early spring I am standing guard at the airport with V. We meet on a piercingly cold dawn. The first birdsong is sung. By their sound and pitch, V unerringly distinguishes the types of birds, talks about them.

Another time, I ask him if he misses his past life and profession. V says that he constantly talks about this with a friend, another scientist with whom we serve. He says that now there is nothing more important than victory, and first and foremost it is necessary to win, and then everything else will follow.

On the other hand, V says that it is critically important to support scientists — a considerable number of them have gone abroad and are unlikely to return. It is important to continue doing research, because due to the war, environmental data series that Ukrainian scientists have been collecting for 50-60 years have been interrupted.

The real scale of damage from the invasion inflicted on Ukraine’s environment will be assessed by researchers at a later date. But it is already clear that almost half of all our national parks and nature reserves have been damaged. And what about our two seas — Azov and Black? What about dozens of rivers? What about fish? Only with time will we also learn about these real crimes of the Russians against ecology.

As I am writing this essay, the funeral of Ukrainian poet and children’s writer Volodymyr Vakulenko, who was abducted by the Russian occupiers back in March in his native village of Kapitolivka near Izyum, is taking place in Kharkiv.

All these months, and after the Russians were pushed out in September, the search for the writer continued. Finally the news came that Volodymyr’s body had been found in a mass grave in the Izyum forest, among hundreds of other victims. He was buried there in early May; two bullets from a Makarov pistol were found in his body, which had been left in the street for a month after he was shot.

Volodymyr lived in the village with his 14-year-old autistic son and was taking care of his father after a stroke. He kept a diary, which he buried in the garden near the house shortly before the abduction.

When the de-occupation of the Kharkiv region began, the diary was literally unearthed by Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina. It is now being preserved in the Literary Museum in Kharkiv and its contents will soon be published.

This is the history of Ukrainian literature nowadays: when Ukrainian writers look for the bodies of other Ukrainian writers taken away by the Russians. It is when a writer with a shovel digs up the diary of another writer who has been murdered.

In his diary, Volodymyr Vakulenko records our faith, which keeps us going: “However, I believe in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. As in God, let Him not be angry with me.”

I spent 100 days in the barracks, together with V and other brothers-in-arms.

At the beginning of the summer, I was sent to Kyiv. V and the other guys were sent east, to the territories retaken from the Russian invaders.

When the internet connection permitted, V would send short messages, stating that everything was fine. Everything was good. Nothing out of the ordinary. I knew from other friends that this was not the case. But that is V and his resilience.

When I speak to V in early December, it turns out that the internet and communications of my brothers-in-arms in the field are better than ours in the historical centre of Kyiv, where blackouts are common. The Russians continue to shell critical infrastructure across the country: they want to leave the civilian population without electricity, without heat, without water.

One day, when V is talking to me, I hear the sound of a projectile from my speaker. The conversation stops for a moment, until it becomes clear that it has missed.

I ask if anything is known about his house and offices in the city of M. Friends and neighbours look after the house and estate. The city is full of the Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov’s forces and Russian soldiers who are strengthening the defence line that will run near his house and where the “Museum of Berries” was supposed to be. Well, the occupiers have already broken into his office in the city of M, destroyed all the equipment and occupied it for their own needs.

I ask V what the war revealed to him about the Ukrainians. V says he feels proud to be Ukrainian. V is proud that together with many thousands of people who had never served in the army before, he took a machine gun in his hands and stood up to defend his homeland. V says that we should be proud that we did not break, but became united.

V is proud of his son, who wanted to join the army with him. As his father, he could stop him only by saying that if necessary his turn would come. Now his son is a volunteer and helps in the liberated territories. The only thing V asks of him is to wear a helmet and not to walk along roadsides that may be mined. This is now a common request for Ukrainian parents to make of their children.

V is proud of his wife N and her steadfastness and ability to support others in need.

I tell V that when a Russian shell destroyed our townhouse in Hostomel, near Kyiv, in the first week of the invasion, I was greatly supported by his words: “We will rebuild everything. We are young. We have to live on regardless of what happens to us.”

N always wanted to have a winter garden with large glass windows. And in this new house, which will have to be built, she and V will create a winter oasis and will be reunited with a dog named Ice Cream.

As I was writing this essay, a dinner with a delegation of famous foreign writers took place. They declared that the purpose of their trip was “to demonstrate support for Ukrainian colleagues”. At some point, a Ukrainian guest told them that he had recently returned from abroad, where he had the opportunity to communicate with people who remembered the horrors of the Yugoslav wars, and how easy it was to find a common language with them through our now common experience. To which a western writer replied: “Of course it was, but the siege of Sarajevo lasted three years, 10 months, three weeks, and three days. No electricity, no water, no food. And what you have got here cannot be compared with what had happened there.”

At times like these, words fail me. It is as if we are invited to participate in a kind of competition, in which we must prove that the Russian invasion is a horror. And it has been that way since 2014. This is a competition in which we should expose our physical and mental wounds, testifying — look, here is our collective trauma.

For professional journalists, this is not the first war they have seen and it won’t be the last. However, for us, this is our only life and our only reality. And we keep looking for the answer: how to define genocide? How many people should be killed and tortured?

When I think about V’s story, when I try to comprehend the fate of my friends and what happened to us this year, I cannot help but think of the biblical story of Job, who had lost everything, but did not lose his faith. And then I think: if a modern-day Job joined the army, he would have to identify himself over radio or phone with a military call sign. What would it be? At the end of the summer, half an hour before leaving for the east, an urgent order came: immediately submit call lists. V smiles cheerfully. His call sign is Lucky. Lucky guy. V says: “Being happy in the army is cool. I hope this will help me to survive in these conditions.”

We do too, friend. We do too.

About the author

Oleksandr Mykhed is a writer and curator of art projects. His non-fiction book I Will Mix Your Blood with Coal, an exploration of the Donbas and the Ukrainian east, is forthcoming in English translation and is available in German, published by Ibidem. He is a member of PEN Ukraine

Illustrations by Jenya Polosina

Translation by Marina Gibson

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Comments