Four generations of black Detroiters on the legacy of George Floyd | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

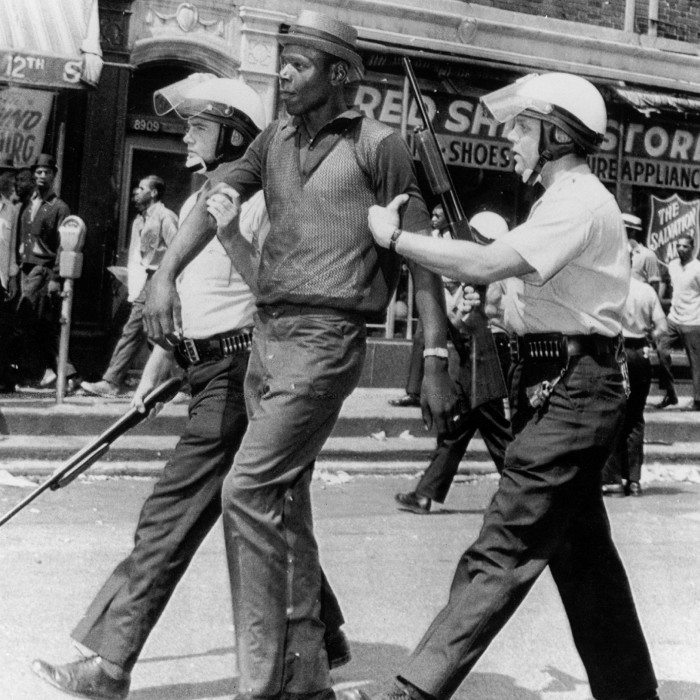

The antiracism protests that have erupted across the US following the death of George Floyd have generated comparisons with the long, hot summers of the 1960s. Nowhere are the memories of those events more searing than in Detroit.

In 1967, the Motor City, as it is known, was the site of an uprising that left 43 people dead, the bloodiest of more than 150 US riots or major disorders that prompted a presidential commission to warn: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

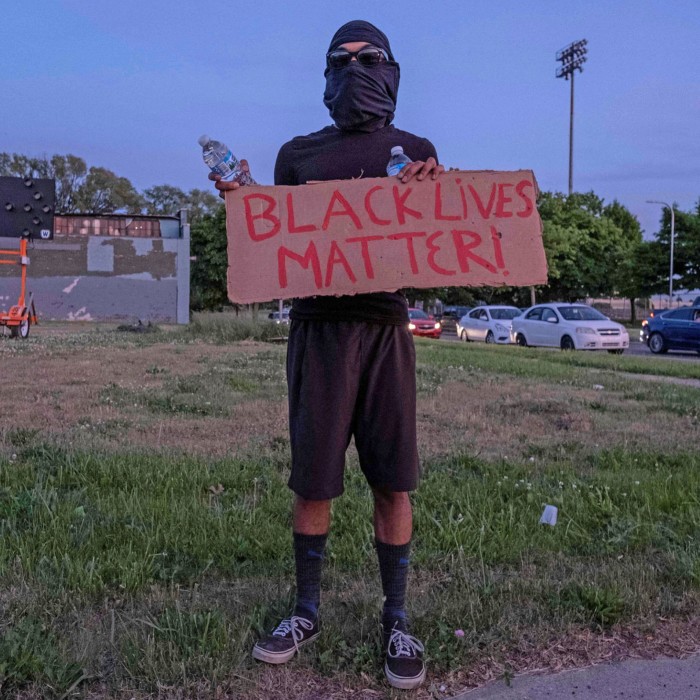

Today, Detroit is nearly four-fifths African-American. Floyd’s death has sparked protests that were less destructive than those in other US cities — and far less violent than Detroit in 1967.

Still, black residents of the city said they remained sad, angry and afraid about the state of US race relations more than five decades after Detroit went up in flames. The FT spoke to four generations of African-Americans in the city for their view of recent events. Here are their stories:

Isaiah ‘Ike’ McKinnon, 76

Ike McKinnon’s grandparents were born into slavery and, as a young black Detroit police officer in 1967, he was shot at by white officers during the riots. He rose to chief of police in the 1990s. Watching the video of a white officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck made him wonder whether racial attitudes have really changed.

“When does it stop, when do people stop believing it’s OK to exterminate people?” he asked. “If you look at the number of minorities in positions they could not have occupied 50 or 100 years ago, that has changed. But have minds changed? No. That’s the big thing for me.”

Officers such as Derek Chauvin, charged on Wednesday with the second-degree murder of Floyd, “should not be in the field of law enforcement”, he said. “[We] need to be cognisant of the kind of people we are recruiting to law enforcement. They have to be screened in a more rigorous manner. There should be psychological evaluations of those in law enforcement.”

Mr McKinnon’s anxieties have been exacerbated by the impact of Covid-19 on Detroit, the biggest city in the state of Michigan. African-Americans have been hit disproportionately by the outbreak, accounting for 40 per cent of Covid-19 deaths in Michigan, which is about 14 per cent black.

Some whites in suburban Detroit have resisted the state’s coronavirus stay-at-home order on the grounds that “they should not suffer just because blacks in Detroit have coronavirus”, he said. “I don’t know how we change the mindset of those people. I think that’s going to be our biggest problem. When people don’t see someone else’s pain.”

He drew hope from the protesters — young people of all colours taking part in what he called a “new awakening” after Floyd’s death.

“People say ‘all lives matter’,” he said. “But . . . black lives have been devalued, that’s why black lives matter. If young white people are now saying black lives matter, that’s a far cry from 10 or 50 years ago when they didn’t say that.”

Tyrone Carter, 58

Tyrone Carter represents Detroit in the Michigan state legislature and was its first member to fall ill with Covid-19 (he has since recovered). He was a five-year-old when the 1967 riots broke out around the corner from his childhood home. “Some things you never forget,” he said.

Too little has changed since then, he said. While he suspects the coronavirus lockdown helped fuel the frustration of protesters, he said Americans took to the streets because so many white police officers had killed black people and gone unpunished.

“To hear [George Floyd] call ‘mama’ and that guy [Derek Chauvin] looking at him like he wasn’t human, that was enough. I think it was the officer’s indifference, how he looked at people like f*** you, and then he puts his hand in his pocket and the other three cowards [other policemen] are just standing around,” he said.

Mr Carter, a former sheriff’s deputy in Detroit, said there was no shortage of sensitivity training and cultural diversity training for police officers, but he maintained that they had not worked to change the minds of enough white people in law enforcement.

“They have grown up their whole lives seeing blacks portrayed negatively by the media,” he said. “If a white male walks into a room, he doesn’t have to come with credentials. But if I as a black male [walk into a room] I have to start at zero and build myself up to 10, while a white male may be a bum but he’s automatically a 10, because of cultural biases and media portrayal.”

Toson Knight, 33

Toson Knight said all he knows about the riots of 1967 he learnt from the movie Detroit, which focused on the murder of three black teens during the uprising. White members of a riot task force were charged in their deaths — and acquitted.

Things were very different this time around on the streets of Detroit, said Mr Knight, who attended the protests every day last weekend. He said police in the city looked to avoid confrontations even when a small minority of protesters looked for trouble.

“Amazing restraint was shown by the police department. I was frankly shocked,” he said. “The first day, they were heavily outnumbered. What I witnessed was a lot of police officers marching with the crowd. At a certain point in time that crowd turned from a protest to a mob. Police officers were running from them. It blew my mind.”

Mr Knight, who says he was “kicked out of 13 different schools and had a lot of run-ins with the law” as a youth, said he believed violence at the protests was fomented by “outside agitators”.

“They had Walkie Talkies and they were very well co-ordinated,” he said. “They were white, but I don’t think it’s the Trump people,” he said, referring to rumours that white supremacists were behind violence in some cities. “If they are racists they are good at masking it”, he said. Mike Duggan, the city’s mayor, has said a large proportion of those arrested at the Detroit protests over the weekend were from outside the city, but he said the city does not know whether they come from the political left or right.

Mr Knight, who lost his mother, an aunt and an uncle to coronavirus, said the pandemic may have contributed to the size of the protests. But he said damage was limited because protest leaders worked with the mayor and police to prevent “what you are seeing in other communities”.

“You haven’t seen Detroit destroyed because people feel like they have a seat at the table here,” he said.

Stefan Perez, 16

Stefan Perez is still in high school, but Detroit’s mayor credited him with defusing a dangerous situation last Monday night when he persuaded a large group of mostly adult protesters to go home rather than defy Detroit’s curfew.

“We stopped a riot — we will be in the history books,” he said, adding, “If we can do that in Detroit, others can, too.”

A high school senior who describes himself as black, Mexican, Puerto Rican and Nicaraguan, Mr Perez lives with his grandmother in south-west Detroit, and rode the public bus to the protest. He recalled his anger when, as a child of 12 or 13, he and a group of black friends were stopped by police.

“We had hoodies on because it was snowing,” he said, but police ordered his group to “get on our knees with hands behind our backs and then they went through our book bags.” Police claimed to be looking for a suspect who robbed a liquor store, but that suspect was white, he said. “They were just doing that for fun”. The incident left its mark.

“Throughout the generations it’s always the same bull, the common thing is change is always temporary, we’ve never had a permanent change at all yet,” he said. “We, [the] younger generation, do a lot of dumb things and yeah, we’re lazy and all, but at the end of the day it only takes a few people our age having something to fight for . . . I feel like the generations can all come together and we can make change.”

On Monday night, people of different generations and genders, different races and sexual orientations “made a human chain”, he said. “It was just beautiful, the way we all came together for one cause.”

Comments