Luxury, philanthropy and the fight against coronavirus

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The first three cases of Covid-19 in Europe were reported in France on 24 January, the day after Wuhan went into lockdown. The first case in the US had been diagnosed four days earlier. As far as most western news outlets were concerned, coronavirus was largely an Asian problem.

At home in Paris, however, Bernard Arnault, chairman and chief executive of LVMH, the world’s largest luxury conglomerate, knew it was a global one. “Despite there being comparatively few cases at that time in Europe, the virus was spreading quickly in China, and China has always been a key partner for our group,” he says, via email, of the Asian consumers who last year overtook the US to become the largest luxury market. “We wanted to show our clear support for our many Chinese employees, customers and stakeholders.” On 28 January, LVMH gave €2m to the Chinese Red Cross.

Kering, Richemont, Versace and Hermès also mobilised, making major donations of, respectively, Rmb7.5m ($1m), Rmb10m ($1.4m), Rmb1m ($140,000) and Rmb5m ($700,000) to the Red Cross and other NGOs in China. It was the start of a succession of significant acts by Europe’s purveyors of fashion and luxury to help hospitals, medical research institutes and other causes pledged to combat not just the virus but its long-term damage to society.

Inevitably, there will be cynics who view the luxury industry’s efforts to help as motivated more by virtue signalling and reputation management than altruism, a desperate effort to infuse what some regard as extravagant products with a kind of gravitas and meaning. But in a time of acute need, luxury fashion in particular has been in a unique position to give: LVMH, Kering and Hermès all recorded their highest-ever stock value in January. Quickly, effectively and not only through pecuniary donations, it has stepped up. Could the groundswell of philanthropy be enough to recast the luxury industry in a new light?

That LVMH is a family-led group that doesn’t need to consult shareholders, adds Arnault, means it has the “agility and skills to be able to help” with a speed that neither a government nor a publicly listed company could easily match. It also has “efficient factories and an entrepreneurial operating structure [that has allowed] us to repurpose our manufacturing facilities.”

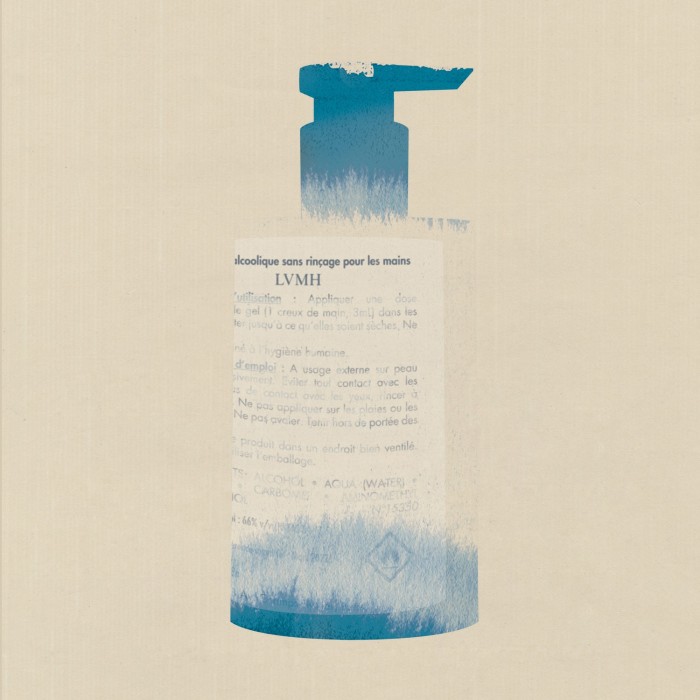

Perhaps the most emblematic gesture came on 16 March – five days after Covid-19 was declared a pandemic, and by which time most of western Europe was facing lockdown – when three of LVMH’s factories (Parfums Christian Dior near Orléans, Guerlain in Chartres and Parfums Givenchy in Beauvais) began to manufacture hand sanitiser. By then, senior executives at the group were in regular contact not just with staff at the Paris hospitals federation AP-HP, but also the government. “At every level of the group, teams [were] actively engaged in this initiative,” says Arnault.

Alcohol gel was what was needed. LVMH’s perfume houses had stocks of ethanol and a supply chain that meant its key ingredient could be replenished. This was the first in a number of initiatives. Later, Laboratoire Cooper, one of the leading manufacturers of hydroalcoholic gels in France, would accept 70,000 litres of pure alcohol donated by the drinks giant Pernod Ricard. In Sweden, demand has been met by Absolut Vodka, and in the US by the premium bourbon makers Rabbit Hole in Kentucky, Smooth Ambler in West Virginia and TX in Texas. In the UK, small premium distillers such as Loch Lomond, Portobello Road Gin, 58 Gin Ltd and Copper Rivet have switched production to sanitiser.

Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, Dior, Guerlain and Givenchy already had stocks of appropriate containers for distributing it because they produced toiletries with the same viscosity as gel hydroalcoolique. When, a fortnight later, Bulgari – which had already purchased a 3D high-definition microscopic acquisition system for researchers at the Spallanzani Hospital in Rome – embarked on the production of 6,000 bottles a day of sanitiser for the Italian health service at its Lodi factory in Lombardy, it used the 75ml bottles earmarked for the shampoo and lotion it makes for its hotels. The doctors LVMH had been talking to had asked for pocket-sized containers, so that it was always to hand.

At first, LVMH’s plan had been to produce 12 tonnes of alcohol gel. By the end of the first week, it had made 20 tonnes. The following week, production rose to 50. “And in the coming weeks, we may be making 80 tonnes a week,” a spokesman tells me. “It is an incredible amount, but it is never enough.”

Almost more remarkable is the muscle the group wielded in procuring and donating masks (28 million surgical ones and 12 million FFP2 dust masks) and even 261 ventilators to French hospitals. It had looked into manufacturing the masks in its ateliers, but for medical-grade accessories, which need to be sterile, “it made more sense”, says Arnault, “to draw on our long-established suppliers in China” and order them instead. A lot of countries “were pushing really hard to get those masks”, a spokesman adds, but LVMH was able to secure an order worth €6m because it was prepared to pay up front.

Its chief rival, Kering, has been making a difference too, procuring and donating three million masks to French hospitals, just one of which can get through over 40,000 masks a day, and funding research at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. Not only is the group supplying personal protective equipment – PPE, as we have learned to call it – it is making it too. Among its fashion brands, Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent’s ateliers were preparing, at the time of writing, to manufacture masks. Gucci is at work on 1.1 million masks and 55,000 medical overalls. Four hospitals in Lombardy, Veneto, Tuscany and Lazio have also received donations totalling €2m from Kering and its houses.

And as we went to press, the Hermès Group announced a donation of €20m to public hospitals in the Paris region, in addition to the gift of 30-plus tonnes of hand sanitiser its fragrance house at Vaudreuil had already produced, and more than 31,000 masks. Importantly, too, it has guaranteed that its 15,500 employees will remain on its payroll, without recourse to government support.

As each country has been affected by this crisis, its brands have mobilised with targeted help for their regions. Across Italy, one of the nations hardest hit, from Armani to Zegna, by way of Canali, Dolce & Gabbana, La Perla, Sergio Rossi, Trussardi and Valentino, the luxury industry’s big names have been making six- or seven-figure donations to hospitals and universities, and switching production in their factories to masks and scrubs. Moncler, for example, provided €10m towards the construction of a hospital in Milan with 400 intensive-care units. Prada, in addition to funding new intensive-care units at three Milan hospitals (Sacco, San Raffaele and Vittore Buzzi), has produced 110,000 masks and 80,000 medical overalls at its factory in Montone.

And in the UK, Burberry has set about retooling its trench-coat factory in Castleford, West Yorkshire, to make surgical and non-surgical masks, and has used its global supply chain to procure and deliver more than 100,000 masks for delivery to the NHS. It has also made significant donations to a range of projects, notably the medical sciences department at the University of Oxford, where it is funding research into a single-dose vaccine on course to begin trials this month, and charities tackling food poverty in the UK.

Neither are these acts completely out of character. At many luxury brands, philanthropic endeavours run deep. Take Rolex, owned by the charitable Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, which is obliged to give all profits not reinvested in the company to the foundation’s philanthropic enterprises. Or the many other brands with established foundations to support a range of causes. It is often by using these funds that they have been able to pile in to do their bit.

In the US, PVH Corp, the owner of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, shipped two million units of PPE and committed to donations totalling more than $1m to a raft of international funds through its foundation. It was, said its chairman and CEO Manny Chirico, the “responsible” thing to do: “There is no roadmap for this crisis, but I know that at PVH we have strong values and connections to our communities.” The same sentiment is echoed by Ralph Lauren, who has made provision for struggling fashion businesses in his foundation’s $10m pledge (in addition to medical relief and manufacturing masks and hospital gowns). “Now more than ever, in this time of need, supporting each other has become our mission,” he said. “It is in the spirit of togetherness that we will rise.”

The everyday exigencies thrown up by the pandemic extend way beyond hospital supplies, acute though those are. As businesses lose revenue, so they need help to retain their workforce. Hence the R1bn (about £44m) donation Johann Rupert, chairman of Richemont, the group that owns Cartier, Chloé, Dunhill, Montblanc, Net-a-Porter and Van Cleef & Arpels, has personally pledged towards helping small companies in South Africa – which was already in recession when it recorded its first case. “Our assistance will be available to all South African businesses,” he tweeted. The billionaire businessman Nicky Oppenheimer, former chairman of De Beers, and his sister Mary have each made a matching donation to the same cause.

Boutique purveyors of luxuries are also responding to the crisis, with gifts in kind. Last month the British perfumer Miller Harris – whose shops, like all those designated non-essential, have had to close – worked with Age UK to donate its entire stock of soap, shower gel and hand lotion to elderly people.

A similar strategy is being taken up by less secure manufacturers of luxury products. Even before the pandemic, the global automotive industry was in trouble, thanks to a combination of falling sales in India and China, and the challenge of finding a workable alternative to the internal combustion engine in line with global commitments to become carbon neutral. But some car-makers are doing what they can. Jaguar Land Rover is not only making NHS-approved protective visors, but loaning the Red Cross and emergency services more than 160 cars, including 27 new Defenders, in order, it said in a statement, “to help emergency teams reach more people living in isolated communities” in Australia, France, South Africa, Spain and the UK. A small gesture, perhaps, but let’s not forget the company cut 500 jobs at its Halewood plant in February.

Is anyone going to be lavishing praise on Lexus? Its token gesture has been to announce it will prioritise repairs to Lexuses belonging to NHS and emergency workers. Nor Mercedes-Benz: witness the announcement that it was donating “the reach of our global Mercedes-Benz social-media channels in the coming days and weeks to help slow the spread of the Covid-19 virus”. We do have reason, however, to be indebted to the engineers at Mercedes-AMG Petronas – the UK-based Formula 1 team in which Mercedes’ parent company, Daimler, has a stake – who have been part of the group developing a new type of breathing aid, trials of which are underway in four London hospitals.

If the travel industry has been less active, that is likely because it is itself fighting to survive. But a few notable luxury hotel owners, whose businesses have had to shut, are making their properties available to health-service staff gratis – figures such as Irish property developer and hotelier Paddy McKillen, who has opened Claridge’s to health workers, providing not just rooms but breakfast and dinner too. “Claridge’s has a duty to step up. Teams from all our hotels have volunteered to help and support the dedicated NHS workers. We are forever in their debt.” Former footballers Gary Neville and Ryan Giggs have done the same with the hotels they own in Manchester.

In the long term, the crisis has provoked much discussion about what luxury might look like in the future. Or how it might have to adapt. The business is praying that consumer behaviours may not be long subdued. But history would suggest that, however deep the recession that will surely ensue, however depleted our savings, the impulse to adorn and indulge will still be innate. Following the Black Death (1347-53), as the historian Peter Frankopan, professor of global history at Oxford University, wrote recently in The Times, “demand for luxury goods shot up (and not only among the wealthy)… and diets improved as people spent more on food, presumably also a reflection of their desire to live in the here and now, rather than save for a rainy day one might never see.”

Likewise, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-20 – which killed more than 50 million people and infected 10 times that number – was followed by the Roaring Twenties, les années folles, an era of bright young things and tremendous creativity in luxury. Chanel (which has donated €1.2m to French hospitals and is “mobilising” its workforce to make masks) opened its fabled premises at 31 Rue Cambon almost immediately after the Armistice in November 1918. The first Cartier Tank watches went on sale a year later. The 1920s saw the launch of Hermès’ Bugatti handbag, a precursor to the Kelly; the Rolex Oyster, the first-ever waterproof timepiece; Elsa Schiaparelli and much else besides. And let’s not forget that within 18 months of the end of the second world war, the young, near-unknown designer Christian Dior launched the New Look, with a mid-calf skirt involving 25m of fabric: outrageous in an era of rationing.

Even if we don’t see innovation on that scale, there’ll likely be a flight to quality, just as in the 2008/09 recession. In the first half of 2009, revenues at Louis Vuitton grew by a double-digit percentage, ensuring those across the whole of LVMH remained more or less what they had been a year earlier. As Melanie Flouquet, head of luxury & sporting goods equity research at JP Morgan, told The Economist that year, “It is incredible that in a downturn the consumer still buys so many Louis Vuitton bags, but she or he does.”

In parallel with hopes for a return to robust sales figures, the philanthropic endeavours of the luxury industry during this crisis might also be the catalyst for a more profound revaluation of its ethical stock. Could its actions positively shift perceptions of a sector that is often vilified as one of the worst expressions of capitalist excess? Perhaps, in years to come, we will see this as the moment that marked a shift into a new era of luxury.

Comments