Will the World Cup change anything for Russians?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The night Russia beat Spain, crowds of people laughed, drank and danced in front of the Kremlin. Red Square belonged to them. In most countries, this would be a totally normal scene after a big football victory. In Moscow, it was extraordinary: probably the largest spontaneous street party here since Germany surrendered in 1945.

Many Russians will remember this month for ever. But does the World Cup leave anything behind? Will it help Vladimir Putin? Will it change the country at all? I’ve been travelling around Russia from Volgograd to Samara, speaking to people who live in crumbling suburban Soviet-era apartment blocks as well as to advisers close to the Kremlin, and I’ve tried to understand.

Every World Cup offers the host nation an image of itself as it would like to be. Russia, for a month, was a land of friendly policemen and glittering infrastructure, where foreigners without visas partied in provincial cities, while western media sang the country’s praises. Russia rarely feels part of a connected world. Briefly, it was the centre of it.

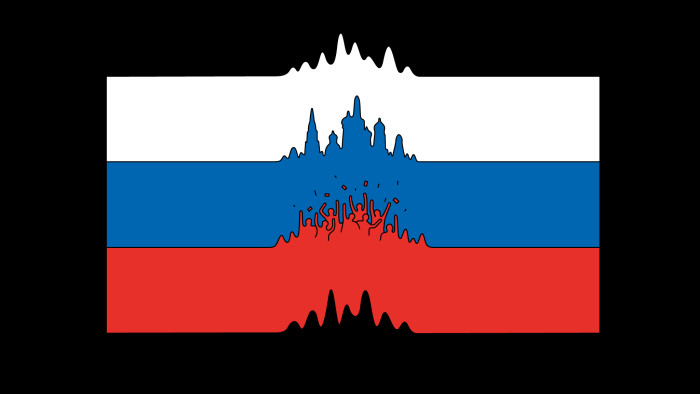

A World Cup is a carnival, and carnivals reverse the usual order. In medieval folk carnivals, men dressed up as women and women as men. This month, ordinary Russians reclaimed their streets from the security forces. Latin Americans and Europeans took it for granted that the streets belonged to them, that they could drink all night on Nikolskaya in downtown Moscow. Quickly, Russians joined in.

But after a carnival, the world returns to normal. Putin’s biggest fear is a popular uprising of the kind he witnessed as a KGB agent in Dresden in 1989. The last thing he wants is for Russians to feel that public spaces belong to them. There’s a video going around of a Russian asking two policemen if drinking in the street will be allowed after the World Cup. “Are you Russian?” is the reply. “Then no.” This tournament will fade like Boris Johnson’s Brexit dream.

It probably won’t give Putin even a short-term boost. During the World Cup, his approval ratings actually fell. That’s mostly because on the day of the opening match, the Kremlin sneaked out a plan to raise the retirement age by several years. The proportion of Russians saying they would vote for Putin fell eight percentage points in a week to 54 per cent, according to the pollsters FOM.

Russians can differentiate. They like hosting the World Cup, but they don’t like struggling financially (average incomes are slightly lower now than in 2008) and suddenly being told to work for longer. They also know that many siloviki — members of Russia’s security services — retire by the age of 45. Come autumn, Putin will have to deal with pensions without the buffer of a World Cup.

Moreover, he missed the peaks of national emotion, Russia’s matches against Spain and Croatia. He didn’t attend, presumably fearing the team would lose. He’s not good at showing joy anyway. And his core message that the west threatens Russia clashed with the tournament’s dominant sentiment. Putin had a mediocre World Cup.

A majority of Russians continue to support him, opinion polls show. These people aren’t all Stalin-loving babushkas swallowing propaganda from state TV. Most agree with him that Crimea is Russian, that Nato has got dangerously close to their borders and that the west overdoes the Russia-bashing. They know that Putin-era Russia is the best time for average people in Russian history. They can mostly live their lives, and read almost anything on the internet (unlike in China), provided they don’t get political or start whining about corruption close to Putin. Few want an inevitably bloody Maidan-style uprising.

But the new Russia’s relative openness has created the most outward-looking cohort of Russians in history: a generation raised on American TV shows, English football and foreign holidays. Russian society is westernising just as Putin’s foreign policy heads the other way.

Many younger people love Russia and its birch trees but they also want to be part of the world — and they find themselves thwarted. A software programmer in Nizhny Novgorod told me about the American investor that liked his company and invited him to visit New York. The US refused him a visa. He thinks it’s because he once worked for a company indirectly linked to the Russian government. He may never see New York.

Younger people are less likely to compare Putin’s Russia to Soviet-era deprivation or the chaotic 1990s. They don’t remember the bad old days. Rather, they compare Russia with other countries. The economist Branko Milanovic puts it like this: the west is already rich; China is becoming rich fast; and Russia, with its low growth rates, is drifting along at middle-income levels, with inequality of wealth possibly greater than in the final years of tsarist Russia. No wonder 31 per cent of Russians aged 18-24 want to emigrate, according to pollsters VTsIOM.

The World Cup won’t change that. It leaves behind only some happy pages for the collective Russian photograph album. These shared memories will long outlast Putin.

If you are a subscriber and would like to receive alerts when Simon’s articles are published, just click the button “add to myFT”, which appears at the top of this page beside the author’s name. Not a subscriber? Follow Simon on @KuperSimon or email him at simon.kuper@ft.com

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments