China still looks scary

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Are stocks finally taking the Federal Reserve seriously? A remarkably strong ISM services reading yesterday sent stocks sliding and the two-year yield up 12 basis points. Perhaps a sampling of next week, packed with Fed speakers and a fresh inflation report. Shivering with anticipation yet? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

A note of caution on China

As quarantine and testing rules loosen, markets are eager for an end to China’s stifling zero-Covid era. They are not waiting to buy: the MSCI China index popped 10 per cent in the past week and is up 30 per cent since the October bottom.

Influential voices on Wall Street are buying the hype. Morgan Stanley on Monday upgraded Chinese equities to overweight, while Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan and Bank of America have all recently made positive noises. In a note out yesterday, Thomas Gatley of Gavekal Research makes the case to embrace the rally:

First and most significantly, it is clear the government has given up on its Covid containment strategy, and that the trajectory will be towards more reopening in coming months . . .

Second, the last few weeks have also seen a significant pivot on property policy . . . the latest measures, which include a central-bank relending program and the lifting of longstanding restrictions on equity market and shadow finance fundraising, shift toward more direct government support, and should be more effective . . .

Even after November’s rally, valuations are low by historical standards . . .

The repressed consumption of the past three years also means that households have plenty of spare cash . . . As yet, neither margin financing nor mutual fund launches show a significant pick-up in onshore retail sentiment. If domestic investors join in, the rally could have real legs.

Gatley does a good job, at the very least, of making sense of the rally to date. That the Chinese authorities are looking for a way out of their Covid-19 dilemma is a material change. Reopening on the table, at least. Surely that’s a good thing.

Still, we are made nervous by pronouncements, like one from Morgan Stanley’s chief Asia economist, that the “base case remains that the market will see a full reopening in the spring”. Maybe, but coming out of lockdown has been very hard everywhere, and China seems unlikely to be an exception. How few elderly Chinese have gotten fully immunised and how little China has invested in hospital beds are big problems that can’t be fixed quickly. Policy jerking unpredictably between partial reopening and lockdowns can’t be ruled out.

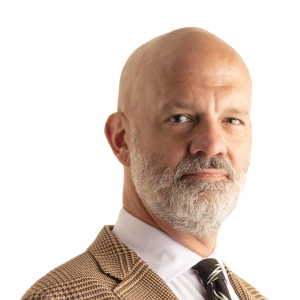

Given that risk, Chinese equities’ valuations don’t look terribly compelling:

Yes, p/e are down a lot from 2021 and are cheap by recent elevated standards, particularly in Hong Kong. But enough to justify the risks? Look at it this way: would you rather own MSCI China at an 11.7 forward p/e or the Taiwan stock index at 12.4? How about the UK at 10? There are plenty of cheap exchanges around the world. China’s outlook has improved, but it still strikes us as a hard sell.

ESG is still a mess

I often complain that ESG investing pitches and research are shot through with vague, incoherent and contradictory claims. Lately, more and more people are making similar complaints. The message, however, does not seem to have reached the sellside. A recent report from Bank of America, focusing on ESG-labelled bonds in Europe, contains a lot of the usual static (along with a few flashes of insight).

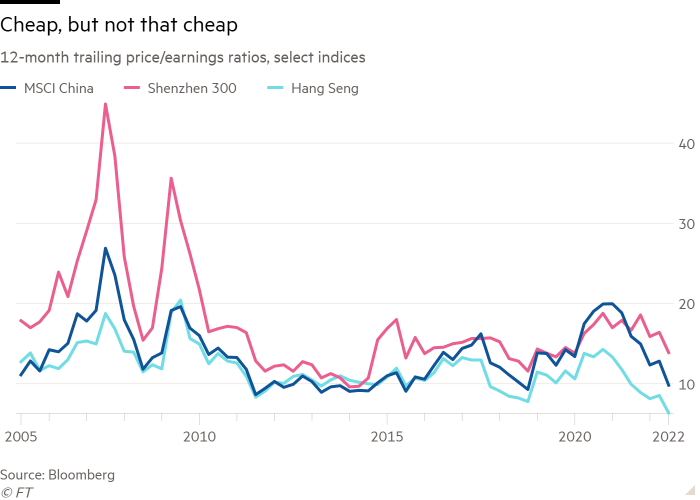

The report is called “ESG & cost of capital: go for green-ium”, and focus on costs of capital is welcome. If ESG is going to make the world a better place, it will do so by making socially beneficial projects cheaper to finance, and socially harmful ones more expensive. The authors calculate the premium paid for ESG-labelled bonds (the greenium) by comparing European senior unsecured ESG-labelled bonds with similar conventional bonds from the same issuers. The greenium is quite variable and sits at around 10 basis points now:

Could a 10-basis-points difference in cost of debt capital make a difference in which projects a company chooses to pursue? I don’t think so, because 10 basis points will be well within the margin of error for a company’s estimates for its returns on any given project. And as rates rise, 10 basis points is becoming less and less important. Still, a tenth of a per cent off projects that line up with the ESG rules is nice for the company, I guess.

But from investors’ point of view, surely the small greenium is good, because a company’s cost of capital is investors’ expected return. Maybe the thrust of the report should have been, “Yay, you can buy bonds that line up with your values while only giving up a sliver of expected return.” But that does not seem to be the point, here or in any other report I’ve ever seen. Instead, we get sentences like this:

Ignore ESG at your debt-cost peril. We show how ESG is being reflected in conventional bond spreads for sectors like oil & gas, utilities and tobacco. Briefly, long-dated issuance from oil & gas and tobacco is down, costs up. Sectors increasingly viewed as ‘dirty’ or challenged face higher risks, lower ratings, and steeper yield curves.

The suggestion here seems to be that higher debt costs are somehow bad for investors when in fact they are, all else equal, good for investors. Investors care not about risk in itself, but compensation for risk. Lower issuance, higher yields, lower ratings and steeper curves could all be most welcome for investors in oil or tobacco bonds, depending on who is getting paid what.

Maybe the authors have something else in mind: that the equity of companies with higher debt costs will tend to perform poorly. In that general vein, they point out that

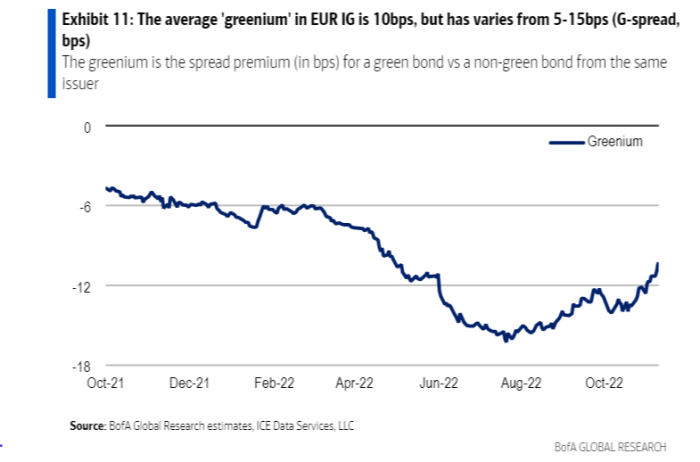

Based on data from MSCI (whose ESG scores are among the of the most widely used by investors), valuation multiples (forward price-to-earnings ratio) for companies with top quintile ESG scores have risen from historically as low as a 20% discount to bottom quintile peers to a 27% premium today, implying a lower cost of equity.

Here is their chart:

But the problem with this analysis is that it does not seem to control for sector, and the recent outperformance of green companies overlaps with the wild growth/tech rally, and growth/tech companies tend to have high ESG scores.

When the report discusses the overall performance of ESG-labelled bond indices with non-labelled bonds, it suggests that the labelled bonds outperform in down markets but not up ones:

This is partly because marginal buyers like central banks and treasuries (important buyers of labelled bonds) tend to take a more buy and hold stance to investing. They are also less likely to be forced sellers in a downturn. Labelled bonds have been more limited in volumes, so there is less incentive to sell given uncertain ability to replace them.

Awkwardly, however, the authors point out this conventional wisdom has not held lately: conventional bonds’ spreads over Treasuries are tighter than ESG bonds’ (though the ESG index is a bit lower-rated, on average). But slightly lower returns on ESG-labelled bonds should not be surprising, given slightly lower expected returns, ie, lower yields at issuance.

Ultimately, the only economic reason to “go for the greenium” is if you think it is going to get wider from here. The authors do suggest two reasons why this might happen. First, “the ECB updated markets on the plan for gradually decarbonising its corporate bond portfolio” and is likely to buy more ESG and less “dirty” bonds in the future. Getting in front of central bank buying is a strategy that makes sense. But this is probably an example of government providing a capital subsidy, not a market solution to social problems.

The second reason to expect a wider greenium, the authors argue, is that over time, as the meaning of ESG labels becomes clearer, investors will make shaper distinctions: “As investors agree on what constitutes ‘good ESG’ and ‘bad ESG,’ as well as good and bad progress, we see room for even greater divergence in debt costs.” I have seen no evidence that this is happening, and no reason to expect it to, given that environmental, social and governance performance is often based on subjective assessments of contested values.

The idea that ESG investing is going to change the world by changing cost of capital remains dubious; the idea that companies with low ESG are more risky than those with high ESG scores is hopelessly ambiguous in absence of valuations; whether ESG labelling meaningfully changes the market’s response to those risks is up in the air; the conceptual muddles of the ESG industrial complex are not going anywhere; and none of this is getting better.

One good read

How do you lose track of almost half a country’s population?

Comments