Why the war on Ukraine is a turning point for markets too

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is chief economist at the Institute of International Finance

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a turning point for European politics, as has been widely recognised in the short space of a few days. What is less widely recognised is that we’re also at turning point for markets.

Europe is in the early stages of a big adverse shock to its economy, which will upend the debate over monetary policy. Think back to just a week ago when there was still collective hand-wringing about elevated inflation. That is now old news. The interesting thing — and the opportunity — is that markets have not yet recognised or priced this.

Take the case of elevated inflation. In a recent analysis by the Institute of International Finance, we warned about the breadth of the inflation rise in Europe, which was being led by genuine overheating in Germany. But Germany is now also on the front line in confronting Russia and one of the most exposed economies to what surely will be deep recession to the east. That changes the inflation debate.

Central banks worry about supply shocks because of “second-round effects”, which is when a strong economy emboldens producers to pass on higher energy and other costs to consumers.

That happens when there is strong demand, which is what gives companies pricing power. None of this applies any more. Uncertainty has risen massively, which will pull down consumer confidence. And that uncertainty does not just relate to obvious geopolitical risks. It goes much deeper.

Countries like Germany and Italy built large parts of their economies around cheap energy from Russia. That must now change, which implies lower growth, wider fiscal deficits and more debt.

The debt nexus for Europe is a tricky one. There have been many voices in recent days criticising Germany for its low levels of government debt, with many treating Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a kind of “told you so” moment. But that’s misguided.

If the last couple of years have taught us anything, it is that big negative shocks can come out of nowhere — recently Covid-19, then Covid variants and now Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. If this isn’t an endorsement of keeping powder dry for emergencies, then what is?

In the eurozone this argument has a special urgency, because markets were already reluctant to buy Covid debt issuance in the run-up to all this. For a key periphery country like Italy, net new debt issuance was largely funded — indirectly — via the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing programme of asset buying to support markets.

With this latest shock, markets’ existing reluctance to fund highly indebted sovereigns will — with bigger fiscal spending needs on the horizon — only grow more acute.

If we’re right, the fact that inflation is no longer a concern makes things easy. Now is the wrong time for the ECB to worry about normalising policy.

Relative price shifts in the eurozone inflation basket are unlikely to broaden out into generalised inflation, which means the coast is clear for ongoing loose monetary policy and — critically — QE that from a fiscal perspective is badly needed.

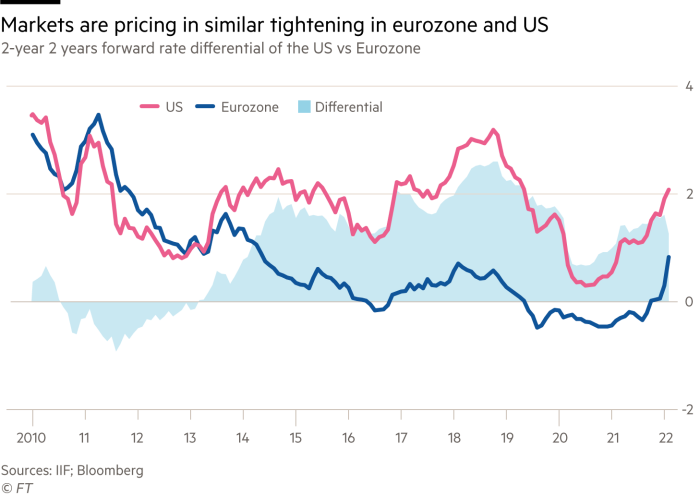

There will therefore be a fundamental decoupling in monetary policy, with the US Federal Reserve pursuing normalisation, while the ECB — given the much bigger shock that Russia’s war is to Europe — keeps easing.

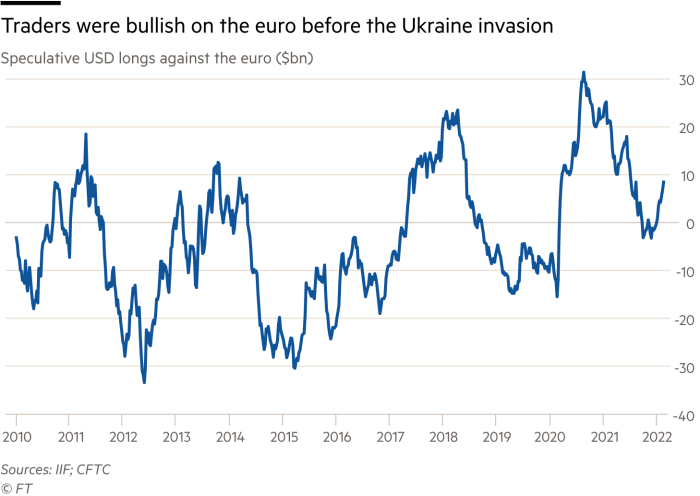

Markets are nowhere near recognising or pricing this. They are pricing the prospect of monetary policy normalisation and rate increases in the eurozone on a par with the US. Speculative positioning in the foreign exchange markets was starting to build a meaningful “long” position on the euro versus the dollar into last week.

In short, decoupling of the eurozone from the US — in terms of growth and policy — isn’t yet remotely built into markets.

We’ve seen all this before. Think back to 2014, which was also a watershed for markets. Russia annexed Crimea early in the year. And then the bottom fell out of oil prices, as US shale took the world by storm.

Amid all this, markets were slow to price in the massive policy shift that was unfolding at the ECB, which would ultimately lead to QE in 2015.

This is because there were genuine mixed signals. Markets thought QE would never be possible given the traditional importance of inflation hawks in the eurozone. It’s the same now. Elevated inflation is the mixed signal that’s holding back markets now. But that is old news, which reflects the world as we knew it a week ago. Big divergence and euro weakness against the dollar is coming.

Comments