Growth stock stars of pandemic tumble into bear market

Simply sign up to the Equities myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

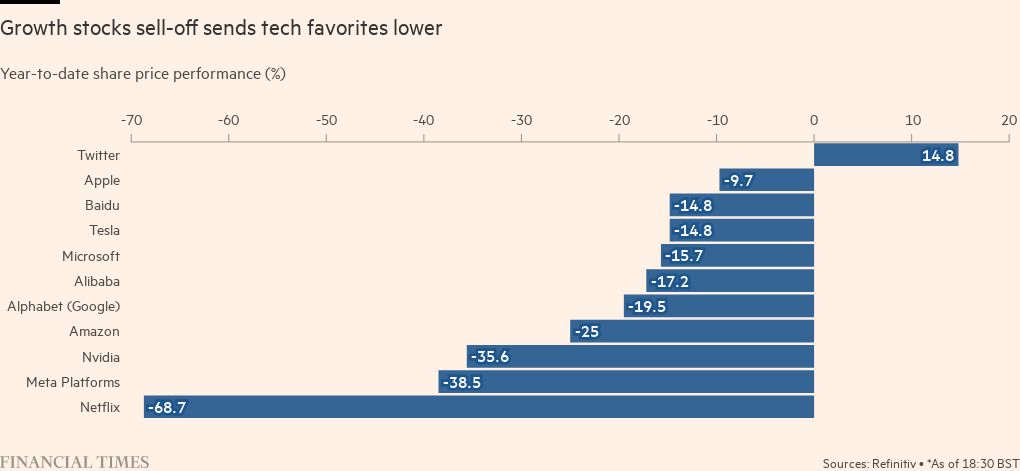

High-growth technology stocks that sparkled in the coronavirus crisis have entered a bear market as shifting consumer habits and the prospect of sharp US interest rate rises force investors out of one of the most lucrative trades of recent years.

The MSCI World Growth index, which tracks stocks with high earnings and sales growth, and includes names such as Amazon, Tesla and Nvidia, this week fell to a level 22 per cent below its peak in November. That decline left it in a technical bear market, defined as a 20 per cent or more fall from a recent high. Other than a brief drop in March 2020, that marks its biggest peak-to-trough fall since the financial crisis.

April has been particularly brutal. The Growth index posted one of its worst performances in at least 20 years this month, with the technology-focused Nasdaq Composite tumbling 4 per cent on Tuesday alone.

With US inflation running at 8.5 per cent and the Federal Reserve expected to raise interest rates by more than 2.25 percentage points by the end of the year, some traders now believe the benign conditions that underpinned a rally of as much as 250 per cent in the Growth index over the past decade have changed for good. Some argue that the days of huge gains from buying speculative stocks with an attractive growth story but little in the way of current earnings may be over.

“It’s now dawning on people that there’s more to investing than handing out capital like lollipops at a school fete to anyone with an idea for flying taxis or carbon-free hot dogs,” said Barry Norris, chief investment officer at Argonaut Capital, who manages a hedge fund and who has been predicting a bear market in most assets.

“Every time there’s been a sell-off in markets there’s been a central bank put,” he said, comparing monetary stimulus packages with options that protect against market falls. “Central banks are not going to come to the rescue this time.”

Among the main casualties this year have been Cathie Wood’s Ark Innovation fund, the poster child of investing in growth companies, which holds stocks such as Coinbase, Block and Spotify, and which is down 48 per cent this year to April 28. Scottish Mortgage Trust, known for its bold bets on tech groups, is down 34 per cent. A number of the so-called “Tiger Cub” hedge funds, spawned from Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management and often big investors in tech stocks, have also been hit hard in recent months.

A Goldman Sachs index of unprofitable tech stocks, which peaked early last year, has fallen 39 per cent this year.

During a bull market that at times appeared never-ending, growth stocks have regularly outpaced cheap, so-called value stocks. Investors holding on or buying during market pullbacks, most notably the pandemic plunge in March 2020, were richly rewarded as central banks injected stimulus, pushing stocks to even higher peaks.

But the prospect of rate rises has hurt low-profit, high-growth technology stocks because those companies’ future cash flows look relatively less attractive. Meanwhile, soaring inflation is limiting central banks’ ability to respond to crises, just as fears are growing about the health of the Chinese economy.

Some investors appear reluctant to let go, despite the rapid drop in benchmark US government bond prices. Brian Bost, co-head of equity derivatives in the Americas at Barclays, said growth stocks remained popular among investors, despite the recent sell-off, with some fund managers still in denial.

“The fact is that [growth stocks] are still trading at very high multiples,” he said. “If something is down 50 per cent, the natural psychology is that it’s really difficult to sell a loser. But I think there’s more pain to come.”

Some stars of the bull market are now feeling the heat. Ark’s Wood, for instance, wrote on Twitter this week that the rising US dollar “suggests that Fed policy already is too restrictive”, even though the fed funds rate is still in a target range that tops out at 0.50 per cent.

Some hedge fund executives have been bracing for a tougher time ahead. Luke Ellis, chief executive of $151bn-in-assets Man Group, told the Financial Times last month that he expected “a tough year for equities”, while Sir Michael Hintze, founder of CQS, has been betting against unprofitable technology stocks, according to investor documentation seen by the FT.

“It is a new regime for markets. It’s going to be tougher to make money for traditional investors,” said Michele Gesualdi, founder of London-based Infinity Investment Partners.

Hedge funds are adjusting to the tougher outlook. US hedge funds, for instance, are running net positions — the balance of bets on rising prices minus bets on falling prices — close to their lowest levels in five years, according to a Morgan Stanley note to prime brokerage clients.

And while some investors have used the market sell-off following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a buying opportunity, Lansdowne Partners, one of London’s biggest hedge funds, said it was “baffled” by this reaction.

“We feel this is profoundly mistaken”, it wrote in an investor letter seen by the FT, adding that “the market dynamics of the last 12 years since the [global financial crisis] have fundamentally changed”.

Letter in response to this article:

Here’s an investment tip for these volatile times / From Tejas Chivukula Bhavani, Singapore

Comments