Llyn Foulkes, New Museum, New York – review

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If you’ve never heard of Llyn Foulkes, it’s because the art world, which incubates plenty of eccentrics, doesn’t know what to do with a painter who careens from crisis to epiphany, who swings from gory despair to slick pop cool and back again, who lets Mickey Mouse plunge him into years of sputtering rage. Over a 50-year career that the New Museum in New York is now celebrating with a dazzlingly weird retrospective, he has made it impossible to answer the art market’s first and crucial question: what does a Foulkes look like? Collectors gravitate to what they recognise; an easily identifiable Rothko brings a higher price than a one-off. Artists accordingly learn to love their formulas. Experimentation is a luxury.

Foulkes never yielded to commercial demands or fears of failure. No sooner did he develop a style or find a following than he abandoned both, striking out into new and idiosyncratic terrain. He belongs to no school and scorns all “isms”. His horror of settling into a rut has led to a luminous if limited reputation as a true American original.

Born in the farming town of Yakima, Washington, in 1934, Foulkes moved to Los Angeles in 1957 to attend the Chouinard Art Institute. There he fell under the fleeting sway of the abstract expressionists but they were too cheery for him. Foulkes affected a grim persona: he kept a pet raven, collected stuffed animals and made fantastically morbid art.

In 1962 the Pasadena Art Museum gave him his first solo show, whose 92 works enchanted the critics. Memories of the charred cities he saw in postwar Germany bleed into paintings glutted with dead animals, singed newspapers and blackened wood. Prehistoric-looking scrawls are thickly veiled with a gritty post-apocalyptic patina.

In “Flanders”, a mess of melted plastic surges off the surface of the canvas, shape-shifting before our eyes. One moment it leaps to life with the wind-borne flutter of Bernini draperies; the next it dribbles gruesomely towards the floor. Rumbling undercurrents of mortality roil the work. A black-and-white photo of Death Valley, California, is stuck in the pliant blob, providing the perfect illustration for the writer WG Sebald’s evocations of contemporary catastrophe: “All was greyness, without direction, with no above or below, nature in a process of dissolution, in a state of pure dementia.” Flanders’ fields, German camps and the American desert merge into a landscape of menace.

After the hooded, flickering glow of that first gallery, the next room is a shock. Within a few years of his dark debut, he had embraced the clean, bright lines and primary colours of Pop. These paintings invoke familiar imagery of the American west: souvenir postcards of cattle, stereoscopic slides, highway stripes and the wide open road, all rendered with cool detachment. The only evidence of the old jagged sensibility is the porous, almost skin-like texture of the desert rocks, which Foulkes achieved by sponging a rag across the canvas. These boulders mine a surrealist vein that’s the one constant of Foulkes’s career. He’s channelling Max Ernst who used the squishy consistency of decalcomania to mimic rough-hewn cliffs, decayed flesh, ruined buildings and landscapes ravaged by war.

Foulkes found eager audiences and critical praise for this new stylistic turn. His work sold. He started teaching at University of California, Los Angeles, won the First Award for Painting at the fifth Paris Biennale and represented the United States at the São Paulo Biennial.

But he couldn’t handle the accolades; he fretted that he had sold his soul. He destroyed a giant rock painting and threw himself into therapy.

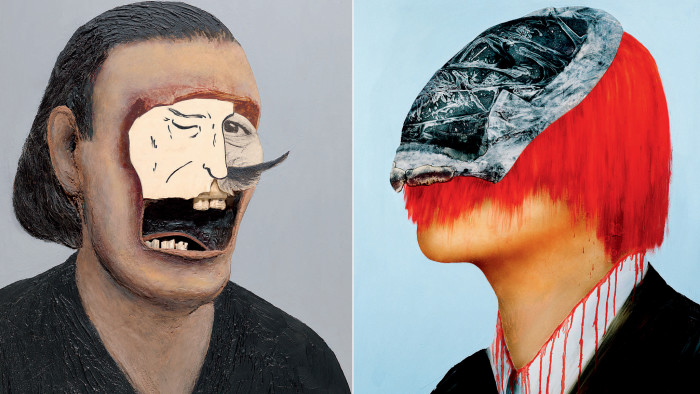

While Foulkes was in the depths of this crisis, a friend who worked in a mortuary invited him to see a freshly autopsied corpse. The flayed scalp set Foulkes’ imagination on fire. He rushed home and poured red paint across a self-portrait he’d been struggling with for years, letting it drip down his neck to the white edges of his collar. This was the first of his “bloody heads” series, realistic portraits transformed by grotesque, gaping wounds and, often, a piece of stationery judiciously applied to the forehead. President Gerald Ford appears in one, recognisable even behind the viscous swell of his lips and the envelope covering his eyes. In another, his father-in-law’s pulverised face reveals a marble-like pair of staring blue eyes. In his military uniform, the man recalls the walking wounded who troubled the streets of Germany between the wars.

Foulkes churned out these seething portraits with monomaniacal urgency until another unlikely trauma transformed his art yet again. His first wife’s father, a Walt Disney animator, gave him a copy of the 1934 Mickey Mouse Club Handbook. The gift infuriated him. The Disney pamphlet candidly discussed strategies for smuggling the brand, with its blithe philosophy, into the minds of babes. Mickey Mouse, it argued, “implants beneficial principles … that children absorb . . . almost unconsciously”.

This was apparently news to Foulkes, who began treating Disney as the quintessential corporate enemy – the emblem of corporate greed, of commercially induced patriotism. The new-found distrust materialised in a series of self-portraits in which Mickey Mouse bursts from his brain like an alien or perches on his shoulder, whispering maliciously in his ear.

Mickey also propelled Foulkes fully into three dimensions. His work since the 1980s incorporates relief and verges on diorama: his troubled universe inhabits the world. He spent five years on “Pop”, inserting a Sony Walkman, Venetian blinds and a working lamp into a scene of horrifying revelation. That’s the artist sitting on a garishly upholstered chair, his shirt collar open to expose a Superman T-shirt. As his children look on, Foulkes’s eyes light up with some insane, lucid fear – and the mushroom-cloud calendar on the wall is open at August 6, the date that Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima.

The painting comes with a soundtrack, which Foulkes composed himself. It blends a surreal gothic ballad, “Once Upon a Time There Was a Mouse”, with a strange, gurgling version of “America the Beautiful”. Whatever atomic-age vision of awfulness the planet must endure, it’s still all Mickey’s fault.

——————————————-

‘Llyn Foulkes’, New Museum, New York, until September 1 www.newmuseum.org

Comments