Regime change is here

Simply sign up to the US economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Good morning. Ethan here, with some professional news. After two-and-a-half years, this is my last edition of Unhedged. In that time Robert and I have had big interviews, good calls, disastrous ones, one bear market, two bull runs and loads of excellent reader mail. Writing this newsletter has been a privilege, and I’m going to miss it.

Later this year, I’ll start as Asia correspondent at The Economist, where I’ll be based in Singapore. Rob is taking next week away to meet central bankers in Switzerland; Unhedged resumes normal service at the end of April. Today, a few parting thoughts from me. I won’t be on FT email much longer, but I’d love to hear from you on Twitter or LinkedIn. Or email the big man himself: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

The world has changed, a lot

When Rob Armstrong hired me in November 2021, interest rates were at zero, inflation was running above 5 per cent, the S&P 500 was hitting all-time highs, 100,000 Russian troops were massed on Ukraine’s eastern border, and I was a fresh economics graduate taking it all in.

We were seeing the world change, though it wasn’t obvious then. Jay Powell’s Federal Reserve dithered on raising interest rates until it had no choice but to act. In late November, Powell told the US Congress it was “probably a good time to retire” the idea that inflation would be “transitory”. That was the end of my first month, when a top concern was whether my wardrobe was sufficiently stylish to sit by the FT’s chief menswear critic. It was also the start of a new regime — cemented when, on February 24, 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The night of the assault, Rob was off, and I wrote one of my first solo newsletters, four months into the job. The feeling of being tossed into the deep end was overwhelming. But it came with a sense of relief; I was far from the only one overtaken by events.

The world US investors face is very different today. But the key question is whether we will revert to the old status quo. Rob and I have wrestled with this constantly. I used to believe the old world would return eventually. The fundamental forces behind low-and-falling interest rates were, I thought, powerful and long-lasting: ageing populations, poor productivity growth, inequality and heavy demand for safe assets (better known as Ben Bernanke’s “global savings glut”). The pandemic was a big shock but was, in a word, transitory.

Today I’d take the other side of the argument:

Since 2021, US interest rates have risen higher and for longer than almost anyone expected. When the consensus is repeatedly wrong in one direction, that tells us something.

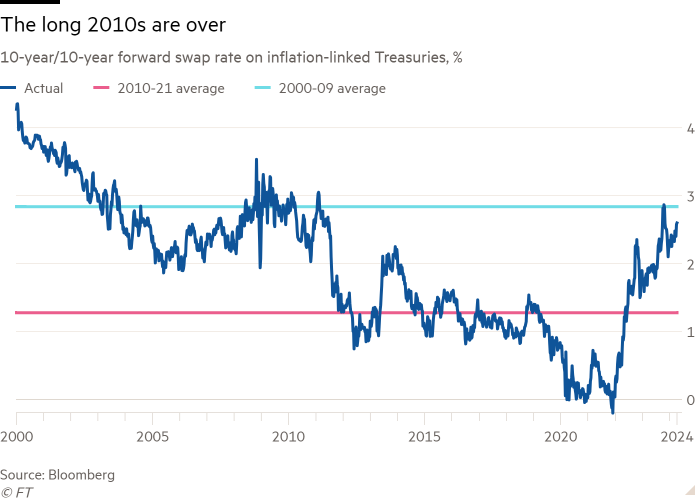

Long-term market expectations have come to recognise a regime change. Far-reaching measures, such as the 10-year/10-year forward swap rate on inflation-linked Treasuries, gives a sense of the market’s view on long-term real rates. On that measure, we are leaving the 2010s behind:

Rates will only return to 0 per cent in a true crisis. Demand is healthy again, thanks to a tight labour market and the consumption it supports. Inflation bows to no forecast, but on balance looks like it will grind lower slowly.

US authorities have become better at managing the financial system. More thought has gone into it since 2008; today you can get a Yale masters degree in systemic risk studies. Practice helps, too. The repo market, the system’s heartbeat, was quickly defibrillated in 2019. The Fed’s alphabet soup of pandemic liquidity facilities were astounding in scope, and the mop-up of Silicon Valley Bank shows how much regulators can do even without a full-blown crisis. The Bank Term Funding Program amounted to a 200bp rate cut injected narrowly into the banking system, according to JPMorgan’s Bob Michele. That such a precise intervention is not just possible, but well rehearsed, should reduce the need for future emergency rate cuts.

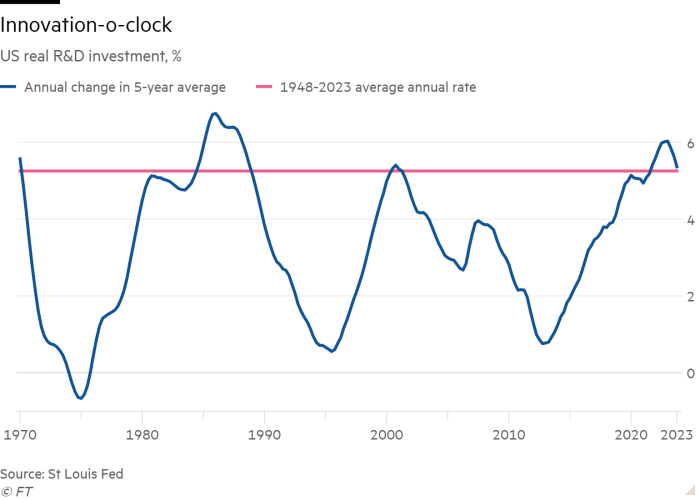

The productivity bull case is the strongest it has been in 30 years. New business formation exploded after the pandemic and never fully reverted. Tight labour markets are improving worker-employer matching. Political will for public R&D investment has materialised. Private innovation investment may follow suit: S&P 500 capex has picked up and US manufacturing capacity is growing at the fastest rate since 2008. Long-run measures of economy-wide R&D have surged:

Both parties now embrace a larger role for government. The evidence for this is simple: the US is running historically large procyclical fiscal deficits outside of a war. This is because political attitudes towards spending have changed, justified by conflict with China, without an offsetting change in attitudes towards taxes. A decade ago, after a limp stimulus, the US had bipartisan deficit reduction. Today, after a bumper stimulus, it has bipartisan industrial policy.

War and climate change mean supply-side risks, which are stagflationary, always linger in the background. Self-serving explanations of the “great moderation”, the period of economic calm between 1980-2007, point to prudent management. The more convincing story is a benign external environment — good luck, in other words. It seems to have run out.

I think we are, rightly, starting to see the 2010s as an anomalous period during which real rates were lower than was healthy. The low-rates fundamentals are still present, but if you squint, there are some signs that they are easing up. On demography, a global mass migration to rich countries is under way. The recent US experience, where a huge wave of border crossers ultimately kept the labour market humming along, shows that ageing societies are not condemned to shrink, if they let people in. On inequality, the tight labour market has raised real wages at the bottom end most of all. Finally, sustained fiscal spending could over time generate more safe-asset supply, absorbing the savings glut (at some risk of a debt crisis).

This is not an argument for US rates spiralling higher. But there is enough here to think that interest rates, after decades of structural decline, have found a bottom.

Of course, the real answer is that we don’t know. That’s what I’ve enjoyed most about Unhedged: the space to think things through alongside a community of generous, engaged and smart readers. The ability to try out an argument one day, be wrong about it, and write about why you were wrong the next day is invaluable. Few errors, factual or analytic, escape the notice of the Unhedged audience. So thanks for the many emails and comments you’ve sent us over the years. If this newsletter has been even half as edifying for you to read as it was for me to write, I’d consider that a great success.

One good read

From the archives: is irony cause or palliative for British decline?

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Comments