Food, fetishism and fine art in the age of Instagram

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the Flemish city of Antwerp in 1564, a young painter called Joachim Beuckelaer sat down to work on an abundant market scene: baskets piled high with glossy crimson plums, huge mounds of pale, veined cabbages, heaped platters of grapes and tranches of spindly carrots, dimpled cucumbers and dainty sweet peas.

The celebration of both nauseating excess and rich beauty was a response to the newfound bounty of the market stall in the Netherlands in the 16th century. Dutch still lives created a new genre of food painting that bloomed throughout the era, and continued to make an impact through the centuries that followed – in Cézanne’s sensuous apples, Morandi’s bowls of fruit, and Andy Warhol’s banana Polaroids. “It’s an eminently human subject,” says former editor of Apollo art magazine Thomas Marks, who’s researching the relationship between art and food. “We all have to eat.”

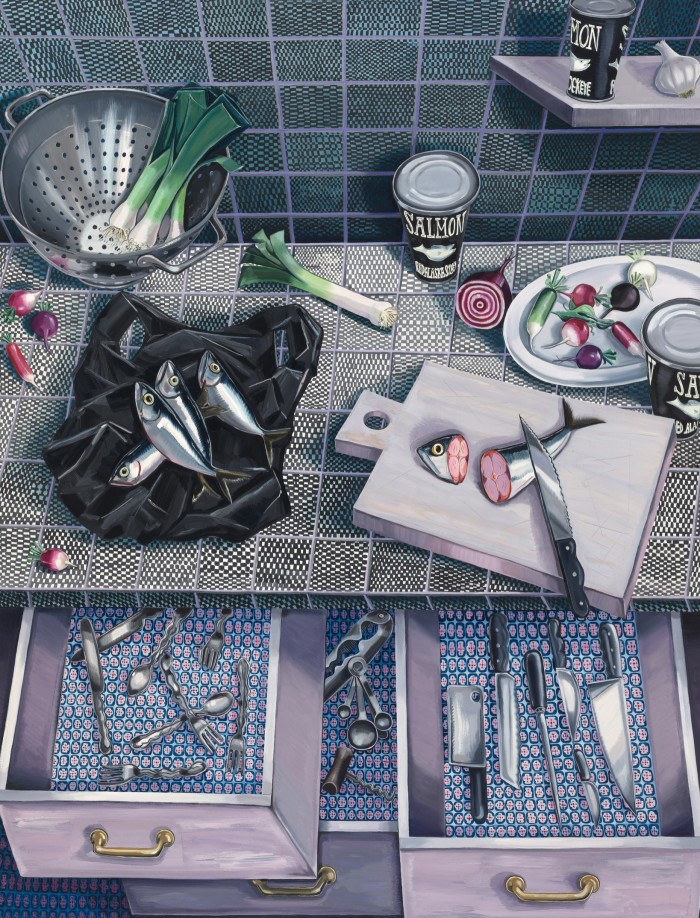

Illinois-born, Massachusetts-based painter Nikki Maloof finds inspiration in Dutch still-life paintings, but her surreal, intensely patterned dinner and kitchen scenes explore a particularly contemporary anxiety: a growing detachment from the animal world. She first became interested in meat and fish because they’re “this kind of insanely grotesque thing that we live with every day – that we somehow stomach every day. To me, that was very fertile ground for something interesting.”

In one painting, a beady-eyed fish head on a kitchen countertop appears almost conscious, while another stares directly at the viewer from a simmering pan. Another painting finds three glistening mackerel unwrapped from their newspaper packaging, on which you can just make out the headlines “Maintaining a sense of hope proves increasingly difficult” and “Night anxiety at all-time high” .“We have a lot of feelings about animals,” says Maloof, whose works sell for between $22,000 and $75,000 at Perrotin Gallery. “They’re both extremely important to us and we revere them, but we also definitely stand apart from them in our minds.” It’s a friction that allows her “to play with dark and light at the same time”.

The Dutch paintings of butcher’s shops are particularly stimulating for Maloof. “A Meat Stall by Pieter Aertsen is amazing because it is so gross,” she says. “There’s tons of meat and entrails. But also, it’s so beautiful. It’s a real feast for your eyes.” Painting animals before, during and after they become food gives narrative to our conflicting emotions, she believes. “Sometimes I think about these paintings as making a meal out of all of those feelings.”

French-Vietnamese artist Julie Curtiss’s paintings toy with our cravings. In her world, animal carcasses hang as if in a butcher’s shop, a roasted and steaming turkey waits on the table, and a slice is cut from a tiered chocolate cake, but look closely and you’ll see that each subject is covered in glossy brunette hair. They tempt us in, only to repulse or even disturb when we realise what we’re looking at. That duality, of simultaneous attraction and repulsion, is the moment she’s drawn to. “I have always been interested in the in-between,” she told HTSI in 2021. “In the tension between opposites.”

Californian painter Hilary Pecis’s playfully messy tablescapes depict the detritus of a table the morning after a late night – champagne, wine bottles, celery and tomato juice for Bloody Marys and Sriracha bottles jostling with coffee pots. For Pecis, this is a way to immortalise a really good dinner or a happy evening. Her depictions of the everyday branded foods that fill our homes – reminiscent of Tom Wesselmann’s ’60s still lives of hot dogs and Rice Krispies – are attracting interest among collectors; she has a museum show at the Tag Art Museum in Qingdao in China, and an exhibition at Gagosian Athens in November, with prices commanding up to $250,000. There’s an element of self-portrait about her compositions; an interest in “documentary – the events that are happening in our daily lives,” she says. Painting leftover food adds “some sort of significance to otherwise insignificant happenings”. A morsel of delight in the otherwise quotidian.

Conversely, Evie O’Connor is interested in when too much significance is given to food: tensions around how we eat, and in “status foods”. “I had an obsession with Nobu, Malibu, a couple of years ago,” says the Derbyshire-based painter. “It was apparent that people were dining there to see and be seen or signal to others on social media that they can bag a reservation and drop $500 on sashimi and wagyu.” She sources images from Instagram or review sites to create her paintings: glowing orange Negronis, or platters of oysters (from £1,300). Broadcasting our food choices, she believes, is used to “elevate us, humble us, reveal our education or aspirations and of course, financial position”.

O’Connor’s fridge paintings show the domestic side of the story: perfectly arranged shelves of fruit and vegetables. “I was researching the ‘fridgescaping’ trend,” she says. “Kris Jenner’s went viral, and I worked from those images. I found the concept that it was probably someone’s job to neatly arrange fresh produce like a work of art so obscene.” Her paintings explore the fact that, as Marks notes, “to show a surfeit of things is perhaps no longer a mark of comfort and abundance, it can be a mark of waste”.

But still, the aesthetic pleasure of food remains as enticing a subject as it was for Beuckelaer. “Why has there been such a long history of people wanting to paint food?” concludes Maloof. “Because it’s beautiful. It’s a great candidate for paint because it’s extremely sensual.”

Comments