Two North Korean defectors: a tale of secrets, lies and love

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It can’t be him, Kim Joo Kyung thought, as she took a seat on a crowded Seoul subway carriage. She stole glances through the swaying jungle of legs and bags and jackets at what looked like the same high cheekbones, cropped black hair, sharp shoulders, even the suit. The train screeched and jolted into a station that wasn’t her stop. Before she knew it, she was following the man off the train into the underground. He walked briskly, and Joo Kyung worried she might lose him. Then she snapped to. There was no way it could be Jang Hyeok.

Heart pounding, Joo Kyung walked back to the platform and waited for the next train. She was in her early twenties, slim and dark-haired. Since moving to the South Korean capital and beginning her studies to become a teacher, Joo Kyung had picked up the fashions and mannerisms of the young people around her, adopting the softer cadences of the southern accent. Her mind turned over the last time she saw Hyeok, two years earlier in North Korea, where they’d both grown up. Ten months after they’d met and fallen in love, Joo Kyung fled the country with her family. The dangers of defecting required absolute secrecy, so Joo Kyung hadn’t given Hyeok any warning or explanation. She’d simply disappeared one day.

After the dreamlike encounter on the train, Joo Kyung found her attention returning again and again to Hyeok. At times her thoughts even drifted towards the unthinkable: reversing the longest, most dangerous journey of her life, just to see him. Later, she told a friend about the incident on the train and confided an idea that had taken hold in her mind. She would find a way to contact Hyeok.

North Hamgyong, where Joo Kyung was born, is a mountainous province in the north-eastern corner of North Korea. With forested alpine ranges and a largely untouched coastline, it contains areas of stark natural beauty. But it is also among the worst-affected regions during the country’s economic crises; food can be scarce.

Joo Kyung and her little sister had a relatively stable upbringing. Smart and hard-working, she graduated from high school with good grades and hoped to attend a top university in the capital Pyongyang, a rare shot at social advancement. But when Joo Kyung was in her late teens, her parents told her they had been the victims of a financial scam, making their debts unmanageable. They could no longer pay for her studies.

Not long after, Joo Kyung’s mother decided the family would try to escape. It was August 2012. Kim Jong Il, North Korea’s supreme leader for almost two decades, had died the previous year, and power transferred to his 27-year-old son, Kim Jong Un. Global intrigue swirled around the new dictator. The family had held power since Kim’s grandfather became Joseph Stalin’s puppet in the wake of the second world war, and western analysts wondered whether the new leader, Swiss-educated and famously devoted to the Chicago Bulls, would finally open up the hermit kingdom.

But little changed for the majority of the 26 million people trapped in North Korea. The economy had never really recovered from the end of Moscow’s patronage after the Soviet Union collapsed, or from the devastating famine which followed in the 1990s. It had been years since the state had provided meaningful support to its people.

Joo Kyung and her family planned to reach family members in China, where several million ethnic Koreans live. With few exceptions, all those fleeing North Korea cross into China somewhere along the 1,400km-long border between the two countries. The best cover is usually found along remote corners of the Yalu River, which runs for almost half the border length and freezes over through the long winters, when Siberian storms plaster the peninsula with thick ice and snow. When the family came to the edge of the Yalu, it was still late summer, the river high and flowing fast. They strung a rope around their waists, tying themselves together in case one of them slipped, and waded across.

The borderlands are dangerous, peppered with police and security outposts on the lookout for defectors. Many successful escapes depend on a shadowy support network: brokers in North Korea and China, who peddle information, burner phones and money-transfer services, and members of non-government groups, some funded by American churches, who co-ordinate a network of safe houses and drop-off points through China and south-east Asia.

Joo Kyung’s family could not afford a broker so they went on their own. For two weeks, they traipsed through areas of swamp and low mountainsides dotted with small farms. While Joo Kyung didn’t dare question her parents, after a few days, she felt a creeping hopelessness. It was late monsoon season, and the air was thick and buzzing with mosquitoes. Her sister’s face swelled with bites. Locals refused to help the family. They picked cucumbers from tiny fields to eat. Finally, they reached a relative in a small rural Chinese village. The relief didn’t last. Within days, a suspicious neighbour had reported them to the police.

China adheres to a border protocol it agreed with the Kim regime in 1986, under which North Korean defectors are seized and forcibly returned. Once back home, they face persecution, torture and hard labour in prison camps; some are executed. Human rights groups argue that by repatriating North Koreans, knowing the treatment awaiting them, the Chinese government is in breach of the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention as well as the UN Convention Against Torture.

“We are all dead,” Joo Kyung thought when the police arrived. Her family was held in China for several weeks before being bundled into an SUV by security agents and driven back to North Korea. In her memory, the journey is shrouded in a grey pall. The security agents appear grey, their faces dark, their features blurred.

In the end, she and her family got off comparatively lightly. Her parents were sentenced to six months in a labour camp, where underfed prisoners toil for hours during the day before returning to cramped, disease-ridden dormitories. Joo Kyung and her little sister were held in a detention centre near the border. The young women were subjected to invasive and humiliating searches, surveillance and interrogations. The authorities wanted to know every detail of their escape, even what kind of rope they had used to cross the river. For long periods, they were under instruction to do nothing but memorise the facilities’ rules and schedule. When does one wake? When does one eat?

Once the family were released, they returned to Joo Kyung’s grandmother’s hometown, their situation worse than ever. They had no money and were social outcasts. Joo Kyung watched as her mother sank beneath the burden of feeling she was at fault for her family’s ruin. Then her father became unwell. “A lot of things didn’t work out for our family,” she told the Financial Times in Seoul. “My father became sick and soon passed away. My mother blamed herself for everything.” But instead of accepting their lot, her mother decided they would try again.

Joo Kyung says her heart still trembles when she thinks of her first encounter with Hyeok. Almost three years had passed since the initial failed escape attempt. She was working for board and lodging at a photography studio in Chongjin, the industrial port capital of North Hamgyong. One day in early 2015, Hyeok, a visiting technician, placed a hand on her shoulder from behind and asked how she was. He had mistaken her for someone else. She spun around. They were eye-to-eye, their faces inches apart. Tall and classically handsome, he had striking angular features that softened and brightened when he smiled.

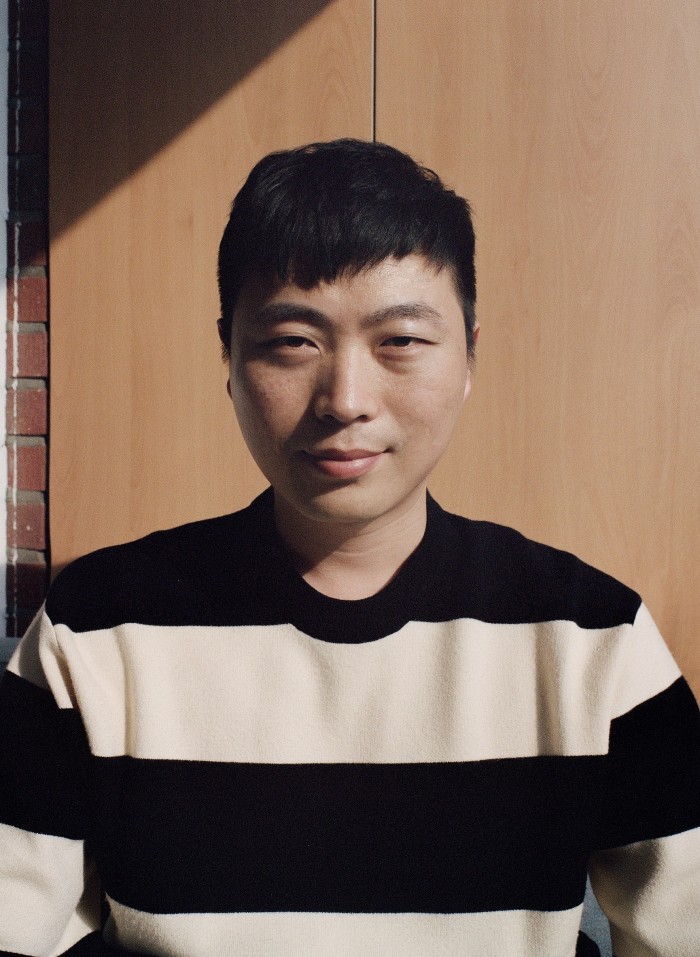

Hyeok had grown up in Chongjin. He was a star pupil, catching the attention of education officials in Pyongyang. In his late teens, he was selected for a national mathematics team and travelled to Beijing, a rarity in North Korea where international travel is reserved for elites or envoys making money for the regime. He went on to study data science at the University of Sciences, a prestigious school in the capital. After graduating, Hyeok was employed by the Workers’ party, which runs the state under the direction of the Kim regime. He won’t talk publicly about the details of his work, for his own security.

Foreign researchers have documented a variety of roles someone with a top class maths education and computing skills might be assigned in the Kim regime. Some develop and police the country’s national “intranet”, a limited version of the web that selected citizens are allowed to access via state institutions. Others are asked to track down and steal nuclear weapons secrets or generate cash for the regime via international financial fraud and cryptocurrency theft. Some are also known to develop lucrative, illegal side hustles, such as rebooting Chinese-made smartphones that allow North Koreans to access banned foreign content and apps.

In the early 2010s, Hyeok, then in his mid-twenties, drifted back from Pyongyang to Chongjin, where he began making money providing technical assistance to local businesses. As one of the few locals to have attended an elite university, travelled abroad and returned to launch a profitable business, Hyeok sparked intrigue and gossip in Chongjin. By the time he mistook Joo Kyung for someone else, she had already heard about him from friends.

Dating culture in South Korea is a labyrinth of unspoken etiquette rules and tests, many of which involve gift giving, chivalry and the marking of anniversaries — starting with 100 days after a couple’s first meeting and 100 days after becoming a couple. In North Korea, moments of romance are snatched between endless hours of work, household chores and errands. Joo Kyung and Hyeok found those moments. If they finished work early enough, they shopped for groceries together, carrying firewood and eggs home from the markets. Sometimes they walked along the beach, looking at the stars. On days they were exhausted, they would place their slippers on the ground, sit on them and eat chocolates.

By the time they began falling in love, Joo Kyung was harbouring a secret. The close attention officials had paid to her family after their attempt to flee had slowly dissipated. Life had seemingly gone back to normal. But her younger sister had not been able to return to school and was working on a farm, and her mother had returned to her hometown, close to the border with China, where she was planning a second escape attempt.

For months, Joo Kyung resisted her mother’s increasingly urgent calls to join the family. She agonised over how and when to tell Hyeok. The thought of him asking her to stay would be bad enough, but the idea of him telling her to leave was also difficult to bear. And she was petrified of being caught a second time. In the end, she lied. She told Hyeok she had to leave town to visit her grandmother. “I couldn’t stay just for the sake of maintaining the relationship,” she said. “I just left, without telling him the truth.”

By late October 2015, when Joo Kyung, her sister, mother, aunt and cousin set off, there was snowfall in the borderlands. The rivers and streams were not yet frozen but were extremely cold.

Since the family’s failed escape attempt, Kim Jong Un had solidified his power, revealing a malicious Machiavellian streak few predicted. His uncle, one of the country’s most powerful men and regent to the young ruler, was executed in 2013. His aunt, believed to have been pivotal in charting his ascent, disappeared from public view. His estranged half-brother was assassinated with a nerve agent in a Malaysian airport in 2017. For Kim, defectors were traitors. The kingdom’s borders were fortified with more barbed wire, border guards and patrols. Punishments for escape became increasingly ruthless.

The FT is withholding most details of Joo Kyung’s journey to protect the route for future defections. After walking for nearly two weeks on the North Korean side of the border, at times wading through snow up to their thighs and crawling under barbed wire, the women crossed the Yalu and into China.

The plan was to make contact with a member of the escape network waiting for them on the other side. But crisis struck almost immediately, when the five defectors were spotted by Chinese police patrolling some distance away. They ran. In the panic, the group split in two, careening in opposite directions. Joo Kyung found herself alone with her aunt, hiding to evade capture. Although she was worried about the others, she knew that she and her aunt had to forge ahead.

They managed to rendezvous with their guide, “a good person”, she said, who was part of a secretive network funded by Liberty in North Korea, a non-governmental organisation run from Seoul and California. Sokeel Park, the group’s South Korea country director, told the FT that it uses an extensive chain of partners and various modes of transport to bring North Korean refugees through China and south-east Asia to safety, with ever-changing routes.

While parts of the journey can be taken by bus, car and boat, days-long stretches have to be made on foot to avoid Chinese surveillance. Sections of road that should take five minutes to traverse can take hours because of necessary backtracking. After several weeks, Joo Kyung and her aunt made it to Kunming, capital of the mountainous and tropical southern Chinese province of Yunnan, which shares a border with Myanmar, Vietnam and Laos. From there, they crossed overland into Laos and took a leaky riverboat to Thailand. As instructed, they handed themselves over to the authorities.

Thai officials process North Koreans as refugees, holding them briefly in a camp in Bangkok for screening before handing them over to South Korea. In December, the pair finally landed in South Korea. Joo Kyung’s mother, sister and cousin joined them two months later. Their freedom was thanks to the kindness of a Chinese official’s wife who had taken pity on them. Rather than sending them into the hands of North Korean security agents, she helped them on their journey south.

In Chongjin, Hyeok hadn’t heard from his girlfriend. After weeks of silence, he travelled to Joo Kyung’s grandmother’s village to find answers. When he finally discovered the truth, he felt unmoored. What had their deepening relationship meant if it could end so abruptly? Perhaps it was doomed from the start, he told himself. For the next three years, he threw himself into his work, achieving a rare level of economic independence in one of the world’s poorest countries. Then, one day in 2019, he received a startling message from a broker in Hyesan, another North Korean border town: a girl in South Korea said she knew him. She wanted him to travel there so they could speak over a safe phone line. Did he know her, the broker wanted to know? Would he go?

For days Hyeok hesitated. He was elated by the idea of speaking to Joo Kyung again. Yet he knew North Korean state security agents didn’t take contact with the south lightly. It wasn’t only himself he’d be putting in danger, but his mother and younger sister too. He bristled at the idea of being so subservient to the regime but knew he could be framed as a spy just for taking the call.

At university, Hyeok had once watched an Indian film in which a character travels to the US. Like all North Koreans, Hyeok had been subjected to anti-American propaganda over the years, and the film’s depiction of Manhattan’s skyscrapers had intrigued him. Now, similar questions came back to him. Was it possible that capitalist countries were, in fact, superior to the socialist paradise wonderland of the Kims? Had Joo Kyung settled in the south and could she, a North Korean, be happy there?

In the end, his curiosity won out. Hyeok travelled to Hyesan to meet the broker, who gave him a handset. As he held it to his ear, a voice he hadn’t heard for years came over the line.

“Jang Hyeok, oppa?” Joo Kyung asked hesitantly, using the Korean for older brother, which is also a term of endearment.

Hyeok found he couldn’t speak.

“Are you Jang Hyeok, oppa?” she repeated, her voice breaking.

Hyeok opened his mouth but nothing came out. He was frozen. In the silence, Joo Kyung began sobbing. And then — click. The line went dead. The broker told him to come back the next day to try again.

Hyeok hardly slept that night. The following day, the broker showed him photo after photo of lined paper filled with Joo Kyung’s handwriting. There was also a picture of a small motorcycle pendant he had once given her.

This time, when the call came through, Hyeok found his voice. It was his turn to burst into tears.

I want you to defect, to come and join me in the south, Joo Kyung told him. Her mother had offered to help fund the escape.

Hyeok felt confused, his natural cautiousness taking over. Weren’t they just re-establishing contact? Seeing how each other was doing? He was comfortable in North Korea, affluent even, by local standards. Defection felt like a dangerous fantasy.

If you’re worried about leaving your family behind, we can help pay for their travel too, Joo Kyung offered.

We’re older now. We’re not just young kids dating, Hyeok replied. We can’t just live whatever lives we want. We have responsibilities.

The call was bittersweet and inconclusive. Each felt sure they were right, neither could persuade the other. It was as though they could no longer recognise each other or the reality of their different lives.

Not long after, Hyeok had a strange dream. He was in America, travelling and excited. He awoke startled but with a clear realisation: being happy in North Korea was like being a frog in a well. “I realised what was preventing me from going to South Korea was a fear, buried deep,” he said. “[But] I was turning my back on the real world. After that dream, I became more honest with myself.”

By late 2019, he was ready to go. With the fee paid by Joo Kyung and her family, Hyeok met a broker near Hyesan, who guided him to the banks of the Yalu. Assured it was safe to cross, Hyeok looked ahead. Bright lights illuminated the river. Even an ant would be visible, he thought. The broker said there was no time to hesitate. So Hyeok went.

From that moment and for weeks to come, Hyeok was a fugitive. He felt as though a gun was trained on the back of his head, that he could be shot at any moment. For 15 days he made his way through China, heading towards the southern city of Chengdu. He was handed from broker to broker, taking slow, tedious routes through swamps and forests to sidestep checkpoints and inspections.

Often, the brokers would only take him a certain distance before sending him ahead to the next rendezvous point alone. He had little choice but to act on blind faith. He knew that, without notice, a Chinese agent could stop him and send him back, to hard labour or even, if Pyongyang’s propagandists wanted to make an example of him, the firing squad. Still, he followed Joo Kyung’s footsteps, crossing from China into Laos, cutting through mountainous jungle before finally reaching Thailand.

The overland journey from North Korea to Thailand is more than 4,000km long. The distance is about the same width as the US, or, as the crow flies, from the UK to Mali. After risking everything to make it to safety, defectors have to spend six months in the custody of South Korean authorities — three months for interrogation by Korean and American intelligence officials, followed by three months of assimilation lessons.

For spy agencies, recent arrivals offer one of the most valuable glimpses into the hermit kingdom. Given the threat posed by Kim Jong Un’s nuclear weapons, every scrap of data, even from ordinary people far removed from the halls of power in Pyongyang, is of interest. The latest products and prices at local markets, for example, can inform their understanding of the state of the economy and the pace of trade with China. Such information feeds into calculations of the regime’s strength and, ultimately, the threat of nuclear war. Authorities must also ensure they are not welcoming an enemy spy.

Hyeok — a government insider with some knowledge of the regime’s cyber and technology programmes — was a particularly interesting case. South Korea’s National Intelligence Service forbids defectors from speaking about their questioning. Three years after his interrogation, he does not talk about what he was asked or what he said.

Once the interrogations are over, defectors are held in the Settlement Support Center for North Korean Refugees, a purgatory commonly known as Hanawon. Set up in the late 1990s, the facility helps defectors adapt to Korean society through education and vocational programmes, including lessons on how to use an ATM and the principles of democracy.

The pandemic hit a few months after Hyeok arrived. South Korea, which had learnt from earlier Sars and Mers outbreaks, introduced universal mask mandates, mass testing and contact tracing. During his Hanawon stay, Hyeok and Joo Kyung conducted their relationship via text and Google Meet video calls. They talked for hours every day. The video calls seemed strange, even with the surgical masks removed. It had been five years since they had seen each other. They were both more cautious, less naive. But each hoped the flame had not died. Just before leaving North Korea, Hyeok had written to Joo Kyung, asking politely, “When we meet, will it be OK if I hug you?”

The day he was allowed to leave, they arranged a time to meet at the rental apartment that Hyeok, like all North Korean defectors, had been assigned. Joo Kyung entered the ground-floor elevator just as he stepped out. They almost bumped into each other. It was a strangely awkward moment. “It was like our souls were very close but our faces seemed unfamiliar,” Hyeok recalled. They went back to his apartment and talked, slowly relaxing and becoming more comfortable with each other. After a few hours, Hyeok repeated his question: “Is it OK if I hug you?” It was.

In early 2022, Joo Kyung and Hyeok were married in Seoul. She was 27; he was 34. When we interviewed them, they were almost like an old married couple: at ease, fond and caring. Determined to create the economic security that eluded her family in North Korea, Joo Kyung has set up an online shopping business while teaching. Hyeok is studying data science, and the couple have created a YouTube channel sharing experiences from their new lives, as well as snippets from the past.

Joo Kyung had always dreamt of a beautiful wedding ceremony. She found excitement about the day came easily to her. Hyeok struggled to enjoy the lead up. He was anxious and unable to properly explain his mood. He resisted making decisions or helping with preparations. Weren’t the vows more important than the ceremony anyway? They had their first fight as a couple. But on the day, the tension melted away. They looked out at a room of people beaming back at them: the small number of family members who had escaped with them and the scores of friends they had made in Seoul, many of whom were also defectors or people who worked in the field, providing support to escapees. Everyone knew the unlikeliness of the love story they were witnessing. None of them had heard of a defection for love before.

After the coronavirus pandemic began, China closed itself off to the outside world. North Korea, even more fearful that an uncontrolled outbreak would overwhelm its healthcare system, sealed its border with China, cutting off almost all trade between the two countries. Kim Jong Un was so worried about infections — and too proud to accept foreign vaccines — that he issued a shoot-to-kill order for unauthorised movements near the border.

Three years later, the tools introduced in an attempt to stop the virus from reaching North Korea are being used for repression. Shoot-to-kill orders, strict curfews and a larger military presence in the borderlands remain in place. Commercial satellite imagery revealed by Reuters last month showed hundreds of kilometres of new security infrastructure along the border, including long stretches of walls and guard posts.

While a small number of defectors have made it to South Korea from China since 2020, the flow of escapees leaving North Korea is thought to have almost completely dried up, according to people working in the field. Hyeok was certainly one of the last. At their wedding, he thought back to those he’d left behind. When Joo Kyung stood up to bow to her mother, she too thought of family and friends in North Korea. “We defectors all have scars,” Hyeok said. “We tried not to show it.”

Edward White is an FT China correspondent. Kang Buseong is an FT reporter in Seoul

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Comments