JPMorgan warns of need for ‘reality check’ on phasing out fossil fuels

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The world needs a “reality check” on its move from fossil fuels to renewable energy, JPMorgan has warned, saying it may take “generations” to hit net-zero targets.

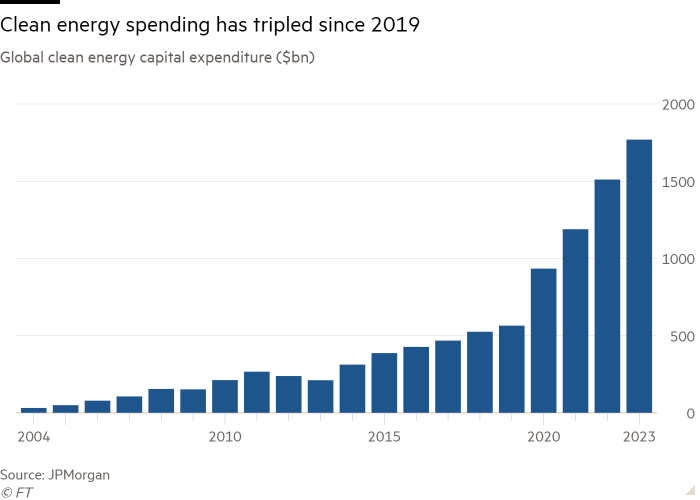

In a global energy strategy report sent to clients this week, the US investment bank said efforts to reduce the use of coal, oil and gas had been set back by higher interest rates, inflation and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

“While the target to net zero is still some time away, we have to face up to the reality that the variables have changed,” Christyan Malek, JPMorgan’s head of global energy strategy and lead author of the report, told the Financial Times. “Interest rates are much higher. Government debt is significantly greater and the geopolitical landscape is structurally different. The $3tn to $4tn it will cost each year come in a different macro environment.”

Malek predicted that the levels of investment required would put pressure on governments to step back from more aggressive energy policies. The Scottish government on Thursday scrapped its ambitious plan to cut carbon emissions by 75 per cent by 2030, conceding that the target was unachievable.

In its report, JPMorgan said changing the world’s energy system “is a process that should be measured in decades, or generations, not years”.

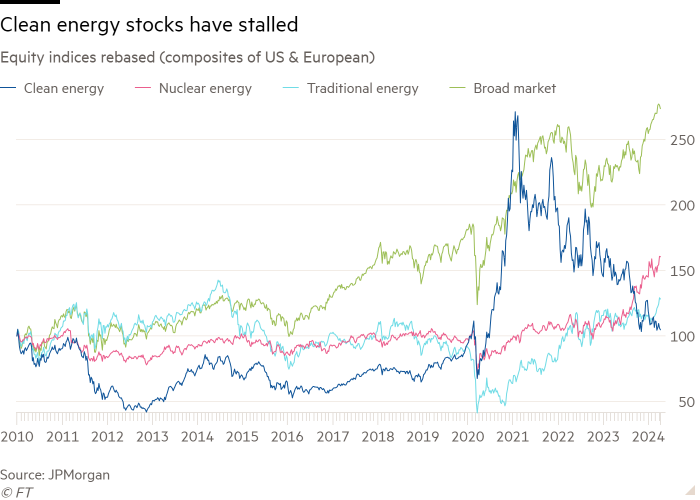

It added that investment in renewable energy “currently offers subpar returns” and that if energy prices rose strongly, there was even a risk of social unrest.

The report came after oil companies including Shell and BP trimmed back their climate targets this year and hundreds of other companies, including Microsoft, Unilever and JBS, failed to set goals that were ambitious enough to be approved by the Science Based Targets initiative, a validation body set up after the UN COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

Malek noted that it was not guaranteed that demand for oil and gas would peak in 2030, as predicted by the International Energy Agency, as the populations of developing countries begin to buy more cars and take more flights.

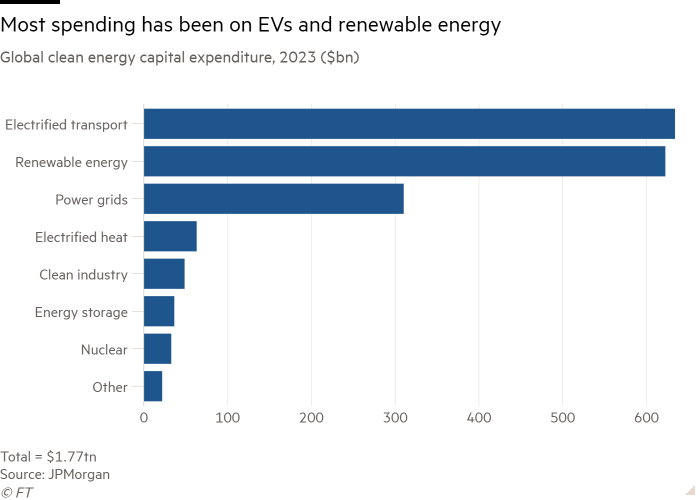

JPMorgan forecasts that the world will need 108mn barrels of oil a day in 2030, and that building more wind, solar and electric vehicle capacity could add a further 2mn daily barrels to this total.

“We are at a tipping point in terms of demand,” Malek said. “More and more of the world is getting access to energy and a greater proportion want to use that energy to upgrade their living standards. If that growth continues it puts huge pressure on energy systems and on governments.”

JPMorgan is a leading financier of fossil fuel projects and low-carbon energy projects. The bank underwrote $101bn of fossil fuel deals in 2021 and 2022, and $71bn of low-carbon deals, according to data from BloombergNEF.

Chief executive Jamie Dimon told a congressional hearing In 2022 that the bank would continue to invest in big oil and gas projects, saying that pulling out of such deals “would be the road to hell for America”, and that the world was not getting the energy transition right.

Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at the Rocky Mountain Institute, disputed JPMorgan’s assertion that the cost of building renewables capacity was becoming unaffordable, saying the annual growth of energy infrastructure spending will only be 2 per cent, as money is increasingly diverted from oil and gas projects into renewables.

“Renewable energy is much cheaper and more efficient than fossil fuel energy, which is why almost all electricity generation capacity now being built is solar or wind,” he said.

Separately, energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie said on Thursday that higher interest rates would make the transition to a net zero global economy “even harder and more costly”.

Peter Martin, Wood Mackenzie’s chief economist, said “the increased cost of capital has profound implications for the energy and natural resource industries”, and that higher rates disproportionately affect renewables and nuclear power because of their high capital intensity and low returns.

Wood Mackenzie added that many companies in the oil and gas industry had low levels of borrowing and would be relatively unaffected by higher rates.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments