What we know about markets in 2022

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning, welcome back, and happy new year. We have managed to avoid the year-ahead predictions game, because we are at least as bad at predictions as everyone else. But it’s the start of a new year, so we thought we could at least lay out what we think are the most important knowns and unknowns in the market now — that is to say where we think we are, if not where we are going.

Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com

Where we’re at as 2022 begins

The knowns:

Monetary conditions are set to tighten, at least until the market or the economy hits an iceberg; this will put pressure on asset prices. The Federal Reserve is tapering its bond purchases at a faster pace. It looks set to raise rates mid-year (though its fundamental bet is still that inflation will prove transitory).

There are other key determinants of the amount of dollars sloshing about, as Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital (our favourite liquidity analyst) points out. There is the Treasury general account — the government’s checking account at the Fed — which is being built up again after being drawn down to almost nothing last month. This means that the government is pulling liquidity out of the system (by issuing debt) and not putting it back (by spending). Another variable: the Fed’s big reverse repo programme, under which it sells short-term debt securities to pull cash out of the banking system, in an effort to keep overnight rates from going negative. If this is wound down, it could offset the taper and the TGA build-up. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank and China’s central bank are tightening and stuck in neutral, respectively.

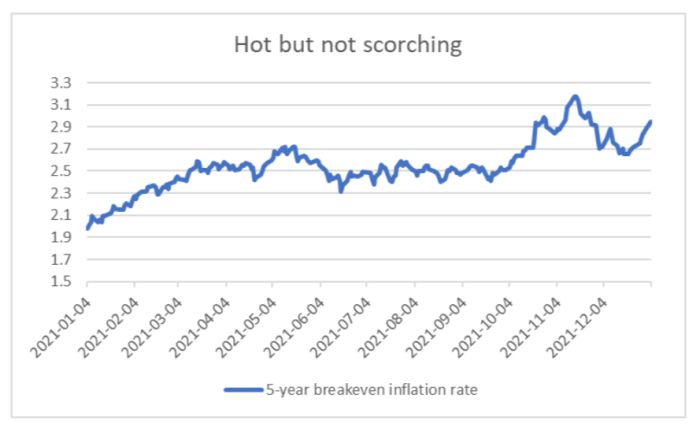

All else being equal, when there is less money around or it is more expensive, asset prices face a headwind. People who feel they have too much cash try to get rid of it, bidding up the price of other stuff.Market prices signal investor confidence that inflation will subside soonish. If you’re betting on inflation or growth boiling over, fine. But the market thinks you’re wrong. Break-evens — measuring the spread between inflation-linked and vanilla five-year bonds — show the market’s thinking. Five-year expected inflation is under 3 per cent:

This could change, of course. Maybe it’s changing right now; yields have been rising across the yield curve in the past few days, and there seems to be a rotation towards cyclicals and banks going on, also somewhat suggestive of more inflation. And:

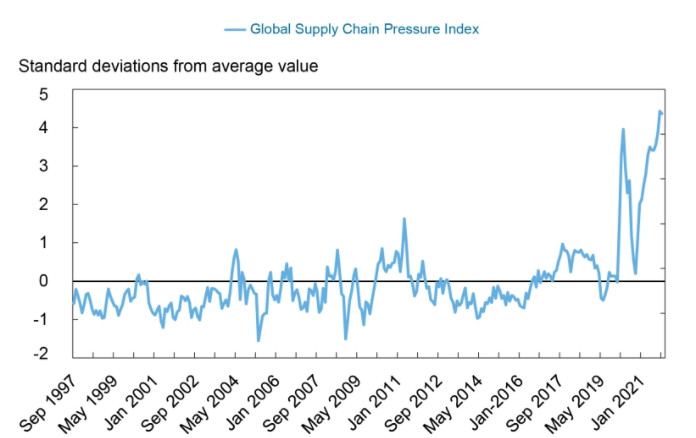

Supply chains remain knotted up, and we still don’t know when that will normalise. The New York Fed’s new gauge of global supply chain pressure tells the story clearly:

Some supply constraints are easing, but most are not. Analyst forecasts are wishy-washy. Some expect a brutal 2022 while others think the second half of the year could bring relief. Notably, even optimists aren’t expecting a full return-to-normal in 2022, but rather a normalisation in certain sectors. Don’t be lulled by headlines later this year saying supply conditions are getting better. The magnitude of supply problems matter as much as their trajectory.

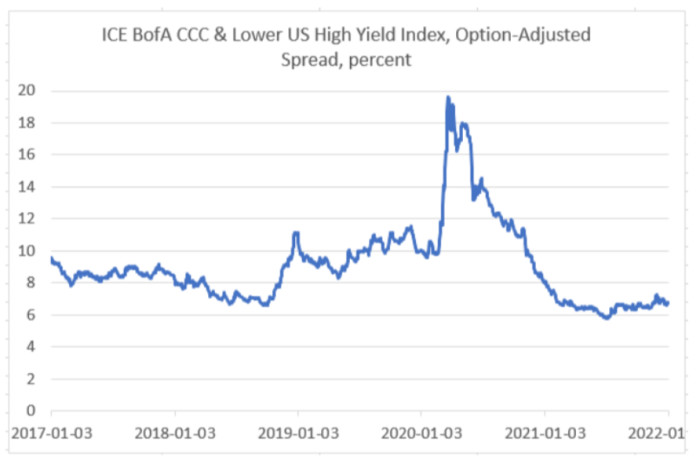

The riskiest equity assets are already in bear-market territory. But junk credit spreads remain super tight. The tech-long-shot ARK Innovation ETF is as good a gauge of this as any. It has plunged 27 per cent since November. But low-quality credit has not skipped a beat. Spreads over Treasuries for CCC rated bonds (data from the Fed) have been stuck below 7 per cent (the very low end of the historical range) for almost a year:

The equity/debt contrast is not all that weird. Creditors are ahead of shareholders in a recovery from bankruptcy. And there are basically no bankruptcies right now, anyway. Still, credit spreads are the fear gauge to follow in the year ahead.

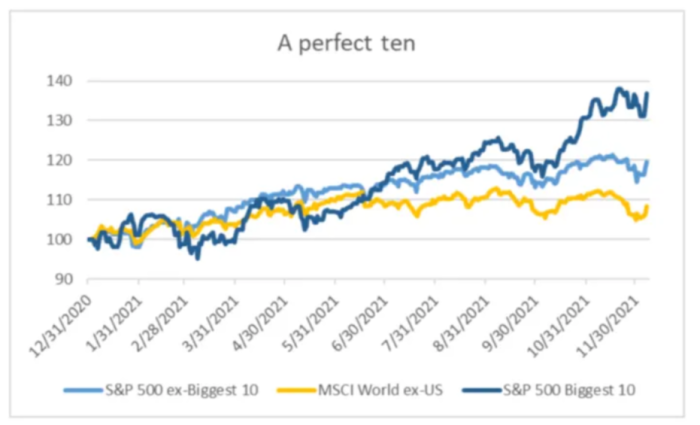

The market is mighty thin. US stocks, as we have pointed out, have been exceptional in both performance and top-heaviness. So much so that holding the S&P 500 last year would have nearly trebled the average hedge fund return. Better yet if you held just the top stocks — what we call the S&P 10:

Globally, the US accounts for the lion’s share of equity gains. And just a few stocks account for the lion’s share of US gains. Market thinness does not — as many market commentators have implied — consistently presage a correction. But it’s still spooky, if you ask us.

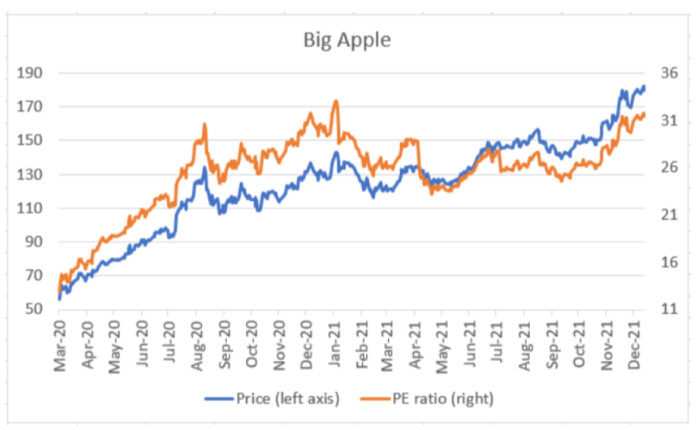

Especially so because the main reason the super-duper stocks have gone up is not profit growth but multiple expansion. There has been some excitement in recent days about Apple tripling in value from its lows during the pandemic to become a $3tn company. But most of the increase is due to a higher price/earnings ratio. Data from Bloomberg:

The relationship between individual stocks’ valuation and their future performance is not determinate, either. All the same — spooky.

The unknowns:

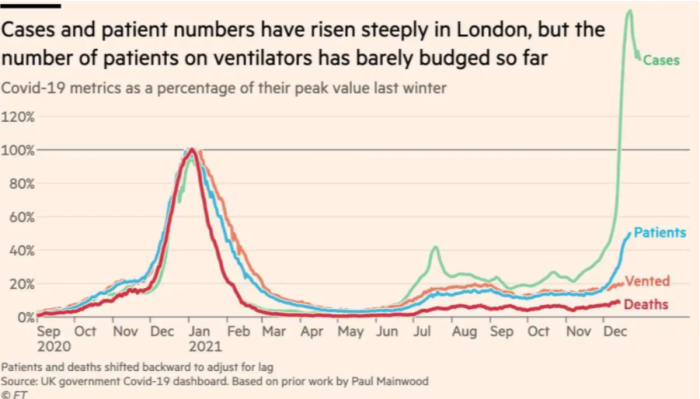

How big a deal will Omicron be, economically? We like the optimistic take on Omicron. As presented, for example, here, it goes as follows. Cases are way up, but hospitalisations are not. The great majority of the vaccinated, and a lot of the unvaccinated, suffer mild symptoms. The new pill (Paxlovid) should improve the odds for those who do get very sick. So, in the case of the US, we could come out the other side of this in (say) a few months without widespread calamity and with a big majority of the country either triple-vaxxed or with resistance from having been infected, or both. That could take the handcuffs off the service economy and the job market at last — and give asset prices a leg up.

We can think of a million ways of this not happening. But charts like this, from the FT using UK data, mixes hope with our uncertainty:

Can China contain its real estate crisis? Economic growth in China is slowing as it shifts, hesitantly, away from its investment-driven growth model. But the massive debt and overbuilding that are the result of that model remain. Can the authorities let the air out of the property bubble without a financial crisis? So far it looks like they have. But the game is still on, and the final score is anyone’s guess. It could be the biggest story of ’22, or nothing at all.

Will Democrats enact more stimulus? Some are clutching on to hopes that Joe Biden’s marquee social-policy bill, Build Back Better, can eventually pass, despite pivotal senator Joe Manchin’s protestations to the contrary. 2022 will be their last chance to pass big legislation before an expected midterm rout.

If Build Back Better fails, pressure could build for Democrats to enact policy by executive decree, such as mass student-debt forgiveness — giving household balance sheets a boost on the liability side. Forgiveness by decree would surely be challenged in court, but the many question marks around US policy could spill into markets.Is Tina enough? This is the big one. Why shouldn’t stocks at all-time highs, in price and valuation, worry us? Because There Is No Alternative: the earnings yields on stocks are still well higher than fixed income yields. There are serious theoretical questions about this argument (shouldn’t low yields indicate lower economic growth, thus lower future profits and lower stock prices today?) but its psychological power and popularity are indisputable. Even if inflation doesn’t drive interest rates up, something else could upend the cult of Tina. A correction would follow. (Armstrong and Wu)

One good read

2022 is an election year. This will matter to markets. Here, from Split Ticket, is a good analysis on the sharpest edge of the Democratic/Republican divide — the diverging voting habits of white Americans with and without college degrees.

Comments