‘Quiet diplomacy’ the weapon of choice for passive funds

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Archbishop Justin Welby’s attack on Amazon’s tax affairs in September prompted a torrent of criticism after it emerged the Church of England’s pension fund holds shares in the online retailer.

Critics argue the Church should simply sell its stake in Amazon — bought as an active investment choice — to signal clear disapproval of its aggressive tax policies.

Selling out, however, is not an option available to asset managers running passive funds tracking an index, even if they disagree on matters such as pay awards to company executives.

This raises questions about their effectiveness as corporate stewards — which have become more acute with passive funds attracting record inflows and accounting for a growing share of managed capital worldwide.

About a fifth of the freely traded shares of the US equity market are now owned by index-tracking funds and passive institutional mandates, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. This underlines the vital role played by the three largest managers in this space — BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street — in policing corporate standards.

Larry Fink, chief executive of BlackRock, recognised this role when he called for “a new model of shareholder engagement” in his annual letter sent to fellow chief executives in January. “Our responsibility to engage and vote is more important than ever,” said Mr Fink, who urged chief executives to redouble their efforts.

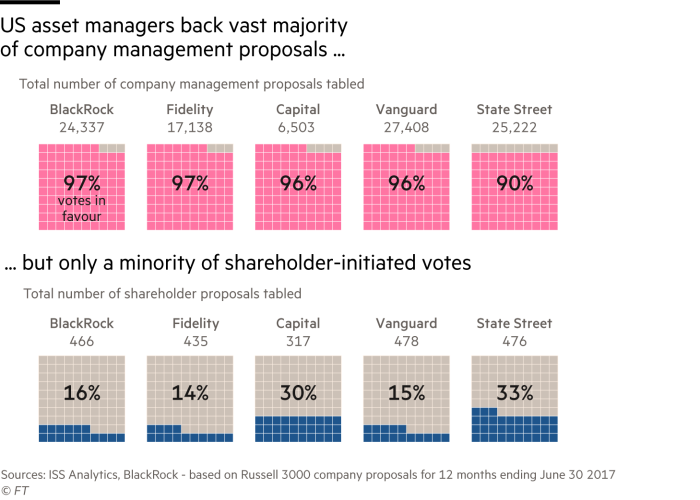

BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street have historically supported management-backed proposals in about 90 per cent of US company votes, the vast majority of which are routine or uncontroversial.

In contrast, the big three gave support to only a small minority of the more potentially contentious proposals tabled by shareholders — though the number of dissenting votes by passive fund managers has been rising modestly.

Passive managers insist these public voting records fail to recognise their successes in influencing companies via private meetings. Measuring the effectiveness of this so-called “quiet diplomacy” is virtually impossible, particularly as many managers are reluctant to disclose exactly how they have exercised their influence.

They prefer instead to report anonymised examples in annual stewardship reports. This has led a number of academics to question the stewardship claims made by passive managers.

In a paper published this year, researchers Nan Qin and Di Wang from the universities of Northern Illinois and Maryland, respectively, found increases in US stock ownership by passive funds were followed by declines in returns on assets and company valuations, measured by the market value of assets as a ratio to book value. They also found that executive pay is more likely to become decoupled from share price performance.

Giovanni Strampelli, an associate professor of business law at Bocconi University in Milan, has pointed to the “acute free rider problem” facing passive managers: any improvements in corporate governance they help achieve create a benefit for all competitors tracking the same index.

The “costs of engagement” are the biggest obstacle to pursuing governance improvements — especially in light of the escalating price war on fund fees. “It is still doubtful whether passive investors are indeed active owners as they have limited incentives to engage in stewardship,” says Mr Strampelli.

Even so, staff numbers employed in stewardship teams have increased across almost all of the world’s largest passive managers, according to data provider Morningstar.

Hortense Bioy, the company’s director of passive strategies research in Europe, says managers have a fiduciary duty to push for changes that will increase shareholder value. “The shift to index investing has not led to an abdication of stewardship responsibilities,” says Ms Bioy.

Efforts to raise governance standards can be complicated by conflicts of interest. An asset manager might have little incentive to vote against company management if it is also a fee-generating client that uses other money management services, for example.

This has led Dorothy Lund, a law lecturer at the University of Chicago, to suggest that passive funds should be restricted from participating at company votes. Legislators, she says, should consider taking action to reduce the influence of passive funds in governance. She believes there is reason to fear that the rise of index-tracking investing will result in “substantial economic harm”.

Mr Strampelli believes this is “too radical an approach”. Restrictions could interfere with funds’ ability to influence policies such as director independence, board diversity and climate change disclosure that required only low-cost interventions, he says.

A more constructive approach from policymakers, suggests Mr Strampelli, would be to consider allowing passive managers to share some of their stewardship costs by jointly establishing a dedicated not-for-profit organisation to undertake engagement activities.

Ms Bioy says disclosure standards concerning company engagements were also “an area for improvement”, given the wide variations in reporting practices among managers.

If clearer disclosures encouraged more passive managers to follow the example of the archbishop, Mr Welby, perhaps improvements in stewardship standards and returns to investors might follow more rapidly.

Comments