Luxuries should be more about the pleasure than the value

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

If you have given yourself the pleasure of acquiring a few luxuries in recent years, then you will have done very well.

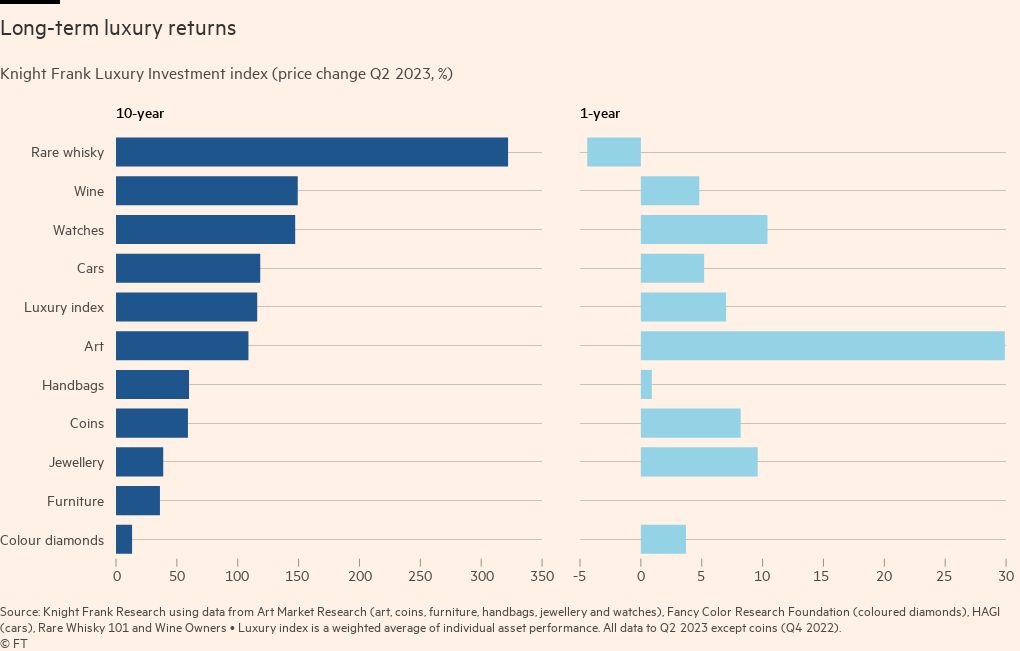

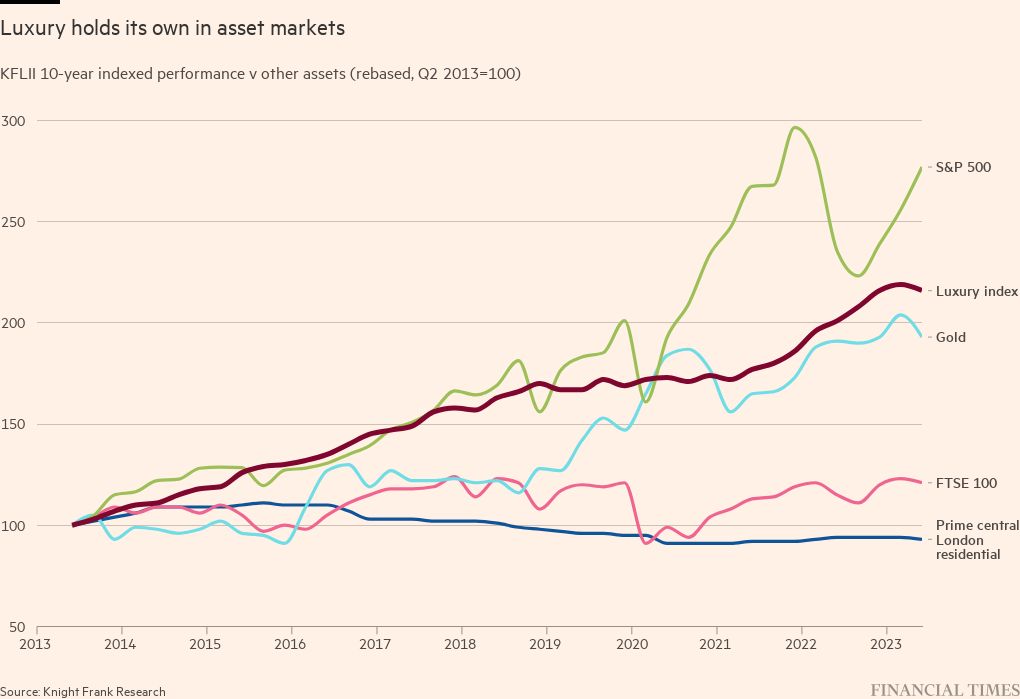

Not only will your gifts to yourself have presumably made you happy, you will probably be sitting on a nice profit. A basket of luxuries, compiled by property agent Knight Frank, rose by 116 per cent over the 10 years to mid-2023.

Admittedly, you would have done even better in US stocks, given the 170 per cent rise in the S&P 500 over the decade. But you would have easily beaten the FTSE 100, the gold price and prime central London property.

Indeed, if you had picked the best performing asset in Knight Frank’s KFLI index — top-class whisky — you would have recorded a spectacular 322 per cent gain. But that’s cherry-picking — you could have made 1,200 per cent on Apple stock.

But the good times may be ending for luxury investor-buyers. The index is up just 7 per cent in the 12 months to June; that’s ahead of the annual US inflation rate for the same month (3 per cent) but behind the UK’s 7.9 per cent.

As the charts below show, without a 30 per cent gain in the art market, the luxury index would have been almost flat for the year. Those mature whiskies actually fell in value, by 4 per cent. As Knight Frank says in its annual luxury report, “growth is starting to slow or even reverse” for some luxury asset classes, excluding art.

And even in art there is a note of caution. It is a market in “the post-pandemic recovery period” rather than “in robust health”, says the report, citing Sebastian Duthy, of the art research company. “ Recent [auction] results suggest growth is already starting to slow.”

All this echoes the slowdown in the luxury fashion and goods industry with leader LVMH, controlled by French billionaire Bernard Arnault, reporting a drop in sales growth in the three months to September to 9 per cent, well down from the 17 per cent increase recorded the previous quarter.

Clearly, concerns about economic slowdown are weighing more heavily on wealthy luxury buyers than a year ago. While many rich families can manage rising consumer prices without much of a break in spending patterns, few can ignore the impact of higher interest rates on the financial outlook. Even if it doesn’t hit them in the wallet, it gives many wealthy people cause for concern.

After all, last year was the first time since the 2008 global financial crisis in which the rich saw their asset portfolios decline, at least in real terms. As the annual Global Wealth Report from Credit Suisse/UBS recently calculated, inflation reduced wealth growth in US dollar terms by 6 percentage points last year — turning a nominal wealth gain of 3.4 per cent into a real wealth loss of 2.6 per cent.

Inflation is now falling, but it is taking its time in the face of geopolitical turmoil that tends to push up energy prices and various supply bottlenecks, not least in labour including in the US, the UK and Japan. Also, many financial experts remain concerned about the huge levels of liquidity pumped into markets in the past 10 years.

All good reasons perhaps to hold back from buying another Birkin handbag, a case of Romanée-Conti wine or perhaps a reassuringly expensive print from Damien Hirst’s recent Cherry Blossoms series.

The wealthy have long been buyers of the rare and the beautiful. They desire what economists call positional goods — stuff that cannot be easily replicated, if at all. Picasso clearly can’t produce another painting. With living artists, supply can be a bit more flexible. But demand for such luxuries has gone global. Never before have there been so many rich collectors in so many countries. They may hold on to their money for a while, but they will be back.

Stefan Wagstyl is editor of FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow Stefan on X @stefanwagstyl

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments