Why do the wealthy escalate disputes beyond comprehension?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

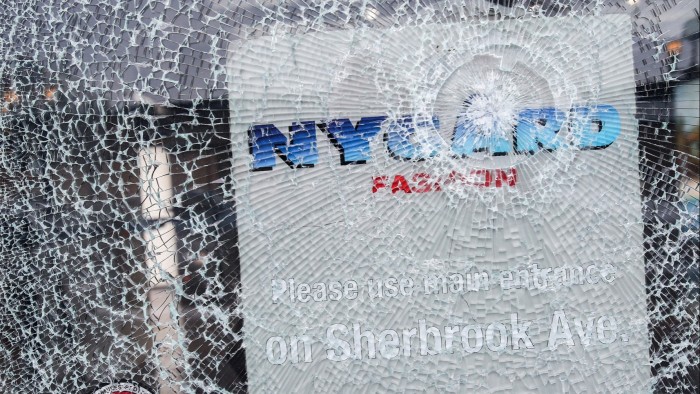

For connoisseurs of high-net-worth spats, May was a vintage month. The feud between Peter Nygård, the clothing mogul, and Louis Bacon, the hedge fund manager, finally ended with a $203mn defamation award against Nygård. This was the largest damages payment ever seen in a New York state court.

The argument, over a shared driveway in a gated community in the Bahamas, has been rumbling on for more than a decade. It began when Nygård alleged that Bacon’s repaving of the road had created foul-smelling puddles on his Lyford Cay property. It escalated over the years, with some truly eye-popping revelations. These include Nygård claiming that Bacon was an arsonist, and allegedly paying protesters at a rally to wear T-shirts and carry signs saying Bacon was a Ku Klux Klan member. All in all, the judge ruled, Nygård had spent $15mn on a smear campaign to destroy Bacon, personally and professionally.

This is an extreme case, but you don’t have to look far to find examples of wealthy people escalating disagreements beyond all comprehension — and spending a fortune in doing so. Nicholas van Hoogstraten, the infamous British businessman, fought a long-running dispute against the Ramblers’ Association over a centuries-old right of way across his estate in the south-east of England. He eventually lost but the battle dragged on to the point where it became the thing he was best known for (which may have been a good thing, as he has had numerous brushes with the law).

The billionaire Barclay brothers, who made their fortune in property and hotels before moving into shipping, retail and media, were involved in a series of legal challenges over the governance of the tiny Channel Island of Sark, which ended following an appeal in part by the UK government.

Why do rich people dig their heels in like this? It can be ruinously expensive and often makes them look like arrogant fools. It’s tempting to say they are so used to winning that they don’t know when to quit. But is this unique to the rich?

Ashleigh Tennent, the founder of the coaching company More Happi, says these are just extreme examples of escalation. “The escalation cycle typically starts with one person doing something the other perceives as a threat. The important thing to note is this perception doesn’t have to be real.” Once the threat has been perceived, “the next stage is moving into anger and the immediate behaviour is to protect yourself. But then, of course, as you protect yourself, the other person takes that as a threat. So it goes from perception to anger to behaviour, and then it’s just a pattern — and it builds. Obviously, with the egos in the way, it can get out of control as the stakes get higher”.

She adds that problems really occur when the outcome of the argument becomes tied up with your identity. This is where the rich may differ (in degree if not in kind) from the rest of us. “If success or always winning is one of your values, you may not be able to let it go.” Clearly, if you have unlimited funds, you do not have to let it go (at least until you get to the nearest supreme court). James Pirrie, a specialist in high-net-worth divorce and mediation at Family Law in Partnership, says the escalatory issues often continue if you take a legal route. “The problem with law is that it doesn’t really deal with emotions, or the motivations. It just trumpets what your conclusions are.”

This means the parties fail to understand what would solve the problem, he says. “You completely fail to understand what’s motivating you to have this passionate sense of what you should be doing, or that someone’s invaded your three inches of turf. All that the law does is convert your motivation into a completely different language, that of law — rights and entitlements and obligations.”

The High Court judge Nicholas Mostyn once noted: “It seems to be an iron law of ancillary relief proceedings that the final difference between the parties is approximately equal to the costs they have spent.” He was referring to a case where the difference between what the parties wanted was £687,000 and the combined costs amounted to £652,000.

So, is there a solution? Yes, it is to try to see the other person’s point of view and find common ground, where you can work towards a solution. This is easier said than done, though, not least if you’ve spent years digging in to your position and convincing yourself the other party is the devil.

Such escalation is not unique to the wealthy. Indeed, Britain is well known for disputes of this sort, many of which seem to involve oversized hedges. One such spat dragged on for 20 years before one party admitted defeat. These often result in significant costs — which, proportionately, may be far harder for those on ordinary incomes to bear — but are less headline-grabbing.

Pirrie says: “I don’t think it is just a high-net-worth disease — it’s just that they’re visible because they can afford to play it out in law.”

Rhymer is reading . ..

Termush, a 1967 novel by Jeff VanderMeer about an isolated luxury hotel full of wealthy survivors after a nuclear war. Atmospheric and surreal, it’s less than 150 pages, which is great.

Follow Rhymer on Twitter @rhymerrigby

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments