There’s nothing dull about the world of natural dyes

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Smashed on sourdough and sprinkled with feta, the avocado has become a millennial symbol of clean living and, some may say, frivolous overspending. But for Brooklyn-based Venezuelan artist María-Elena Pombo, the superfood’s popularity – domestic consumption having soared sixfold from 436m pounds to over 2.6bn pounds between 1985 and 2020 in the US – presents an aesthetic opportunity. “An often overlooked property of the avocado is its dyeing capability,” she says, “which is highly dependable, due to the tannins it contains.” If you boil the stones, they will produce a pretty, pale – and fittingly millennial – pink.

Pombo has been running workshops under the name of Fragmentario on how to extract colour from avocado seeds since 2016. Her Avocado Tour has taken her from Tokyo and Osaka to Berlin and Barcelona, pausing at London’s Somerset House in June where her exhibition La Rentrada explored how the Venezuelan economy, a country heavily reliant on oil exports, could take advantage of avocado seeds to create alternatives to fuels and materials. And it’s not just avocados that have featured in the artist’s explorations of natural dyes – she’s worked with a variety of plants for workshops and client commissions.

Pombo is channelling an age-old practice. Plant-based dyes were used up until the mid-19th century when synthetic alternatives were developed. Indigo and saffron were used in India, for example, and the madder root was cultivated in Europe to dye military uniforms red. Today, as the textile industry’s use of chemical-heavy dyes comes under scrutiny, these methods of applying colour are being explored afresh.

Dublin-based Kathryn Davey started experimenting with indigo dye while making dolls for her three children. She now dyes her own range of products – from wool socks to linen napkins and tablecloths – and collaborates with like-minded brands such as the organic underwear label Pico and childrenswear line Apolina. “I’ve also been teaching natural-dye workshops for the past couple of years and they’re always sold out,” she says. “For me, there’s the environmental aspect of it, but there is also definitely something nourishing and soothing about the colours. I work a lot with cutch [catechu], which comes from the heartwood of the acacia tree and creates really beautiful shades – a whole spectrum of earthy tones.”

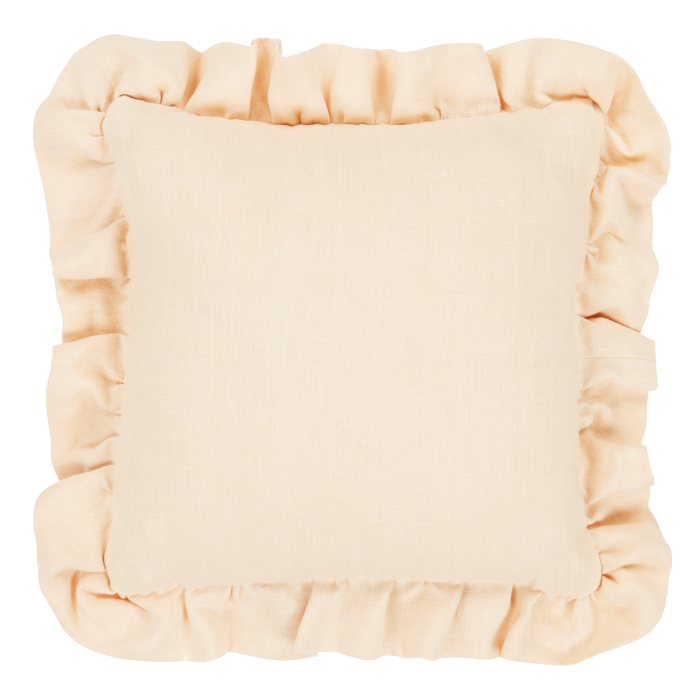

Those exploring the medium do so in many ways, from the painterly to the scientific. Textile designer Ellen Mae Williams reinterprets the Oxfordshire landscape in vibrant abstract spatters and brush marks, using food waste from onions and avocados, as well as plant dyes such as chlorophyll (green), madder (pink) and logwood (purple) to create linen tablecloths, napkins and cushions. In the Hague, Nienke Hoogvliet has set up a design studio that explores natural-dye alternatives to mainstream textile practices. Her projects have involved using herbs to dye and infuse a handstitched linen quilt, creating yarns and dyes from different types of seaweed, and using materials created in wastewater processes. She found that Kaumera, a bio-based byproduct of some water-purification plants in the Netherlands, “makes textiles absorb dyes better, so less water is needed and less is polluted”. She also discovered that two natural dyes – Anammox and Vivianite – could be extracted from wastewater, showcasing her findings as a kimono at Oxfordshire gallery Informality earlier this year.

In Los Angeles, Max Kingery’s approach to natural dyes is also driven by research. “We’re not just making pretty colours,” says the co-founder of fashion label Olderbrother. Each season he experiments with different dye materials and processes, showcasing his clothing alongside immersive shop-scapes at his Venice Beach base. When in 2018 he presented a collection dyed with chaga mushrooms foraged in the Adirondacks, the space became a living fungi terrarium. For AW21 he has focused on fermentation – everything sewn and dyed in California. “We develop all of our processes, our recipes in-house and just experiment, experiment, experiment,” he says.

One of the main criticisms of natural dyes is that they often use chemical mordants to “fix” the colour to the fabric, and while Kingery keeps his formulas close to his chest, he lists plant tannins, oak galls, alum (potassium aluminium sulphate) and iron oxide among Olderbrother’s mordant repertoire. “Our processes are 99.9 per cent natural,” he says. “We don’t use anything that you couldn’t drink.” Another criticism is that natural dyes are much less long-lasting than their synthetic counterparts, but for Kingery this only adds to the appeal. “There is a bit of wabi-sabi to our stuff,” he says.

Other brands are coming round to a similar eco-first way of thinking. When Barcelona-based vegan sneaker brand Saye launched its first clothing collection last year, it opted for all-natural dyes “not to get the perfect colour but to use an eco-friendly solution”, says co-founder Marta Llaquet. In interiors, Ochre has launched Ochre Wild, a collection of handcrafted rugs in hemp, ramie, linen and silk that are coloured with turmeric, marigold, indigo and madder root; Caravane has created a series of table mats and rugs with plant-dyed reeds woven into ikat patterns; Noble Souls uses special dyes that are 100 per cent natural for its upholstery; while Charlotte Lawson Johnston has founded Cloth Collective as a British group of growers, spinners, weavers and dyers, including Katherine Preston, the former head of studio at Fermoie fabrics. Using 100 per cent compostable fabrics and dyes from bio and botanical waste, Cloth Collective’s aim is to scale up this “cottage” industry to create climate-positive interior fabrics, and collaborate with brands such as shoemaker Le Monde Beryl, for whom they developed two plant-dyed natural linens for its SS22 collection.

San Francisco loungewear label Harvest & Mill takes a similar home-grown approach to its WFH-friendly organic cotton range, which incorporates limited-edition T-shirts naturally dyed with California clay by Oakland-based artist Rosa Novak, as well as several entirely un-dyed options, their natural hues created by using heirloom varieties of cotton that grow in subtle brown or green. Its approach is holistic. “Sustainable design has to take into account the origins of the materials, who sewed a garment, does a dye factory pollute local air or water and so on,” says founder Natalie Patricia. “Sustainability is about systems and communities.”

In larger-scale production, calculating the environmental impact of dyeing must also take into account the amount of water and heat used. Llaquet sums up the advantages of natural dyes: “They do not contaminate water, they produce low CO2 emissions thanks to cold dyeing, they save up to 40 per cent in water consumption, and they produce harmless waste and recycling water for future dyes.” Porto-based textile company Tintex, which has been crafting jersey fabrics for over 20 years for the likes of Portuguese designer Maria Gambina, states that its patented plant-dyed Colorau fabric uses up to 60 per cent less water than conventionally dyed textiles.

Could natural dyes become the norm across the textile industry? “The challenge is to get diversity of colours,” says Tintex CEO Ricardo Silva. “Today, we have light yellows with thyme and several browns with other ingredients like chestnut. Greens are on the way. Due to the colour-range expectations of the market, I believe a hybrid production with herb-based and synthetic dyestuffs will be the scenario, at least for the next few years. In parallel, some long-term investigations using biotechnology – with bacteria, for example – could offer alternatives to the synthetic dye stuffs currently used. At that time, we might envision a fully bio-based textile dyeing process – that’s a very real possibility. Stay tuned…”

Comments