Review: ‘Painters’ Paintings’ at the National Gallery, London

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The paintings that painters own are not always masterpieces, but they are rich with double meanings: we respond both to the expression of the artist, and to another painter’s reading of that utterance.

Consider, for instance, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s “Italian Woman”, a hieratic fleshy head carved from a dark background, in the company of Lucian Freud’s visceral grainy old-age “Self-portrait” and a granular, curving nude on crumpled sheets, “After Breakfast”. See these together for a few minutes, and the abrupt, rough-hewn brushwork of the French painting, as well as the model’s formidable yet enigmatic presence, start to exhibit intense kinship with the 21st-century compositions Freud made soon after acquiring the Corot in 2001.

Add an awkward Cézanne brothel scene of two lovers and a maid, “Afternoon in Naples”, still privately owned, which Freud thought “erotic and funny” and paraphrased in his clumsy disaffected nudes “After Cézanne”, plus Constable’s distillation of innocence “Portrait of Laura Mowbray” — pale English winter light on diaphanous young skin — and you understand how a painter’s art collection is a self-portrait, reflecting his ambitions and tensions in answer to homage and influence.

Freud hung “Italian Woman” in his bedroom and bequeathed it to the National Gallery, where its arrival sparked curatorial interest in other works once owned by artists. Painters’ Paintings, an intriguing, uneven show, is the result: it displays pieces owned by Freud, Matisse, Degas, Leighton, Watts, Thomas Lawrence, Reynolds and Van Dyck in a succession of artist rooms arranged — for reasons that emerge all too clearly — in reverse chronological order.

The first three galleries are the weightiest, both by size and content, for it is only from the dawn of modernism that dynamic issues of emulation versus rejection, appropriation, distortion, parody, competition in pushing avant-garde experiment, come dominantly into play. That is why the heart of the show lies in the story of how successive generations of modern art’s gravest traditionalists became radicals: first Degas, most conservative of the Impressionists, then Matisse, who more than any of his École de Paris peers looked to art of the recent past to forge the future.

The painting that links them is Degas’ “Combing the Hair”, an everyday scene with a violent undertow where, in livid saturated oranges and reds, framed by a heavy velvet curtain, one woman tugs the abundant auburn tresses of another. The National Gallery acquired this proto-Fauvist work from Matisse, who bought it at the studio sale following Degas’ death, in 1917. Not only its flamboyant colour but the mood of casual intimacy and concentration on self-absorbed female figures are furthered in his series of women in interiors, begun in Nice in 1919, such as “The Inattentive Reader” here.

Matisse was an impassioned collector for whom every acquisition had creative purpose. At the end of his life he hung at home a Picasso portrait of Dora Maar, majestic but broken against a grey ground, for “the anguish of the figure, the terrible expression of the face” helped him achieve the pathos he sought in his last decorative scheme for the chapel at Vence.

“Picasso shatters forms,” he said. “I am their servant.”

The pictures Picasso and Matisse kept or sold, including each other’s works, keenly demonstrate their own evolving formal concerns. When young and penniless, Matisse pawned his wife Amélie’s wedding ring to acquire Gauguin’s primitivist, flattened “Young Man with a Flower behind his Ear”, an exceptional private loan here. And he spent Amélie’s dowry on Cézanne’s ungainly “Three Bathers”, whose pyramidal composition and rigorous assembly of forms heralded a pictorial revolution.

“It has sustained me morally in the critical moments of my venture as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and my perseverance,” Matisse wrote. “In moments of doubt . . . I thought, ‘if Cézanne is right, I am right’.”

Freud, Matisse and Degas all collected Cézanne, who towers over this exhibition. For Degas, Cézanne was a younger creator of awkward, questioning work — especially, here, an angular, unsteady, psychologically ambiguous “Bather with Outstretched Arms” now owned by Jasper Johns — to be explored alongside innovations by Manet (“Woman with a Cat”, “The Execution of Maximilian”) and those bought to support the struggling Gauguin, such as the Tahitian “A Vase of Flowers”.

Against these, Degas balanced a distinguished collection of solid neoclassical and romantic paintings, cornerstones of his own values of academic draughtsmanship. This show pairs his austere, assertive “Self-portrait” aged 20 with Ingres’ queasily realistic depiction of arrogant, darkly watchful “Monsieur de Norvins” and unites pastels by Degas and Delacroix sharing mastery of texture and colour.

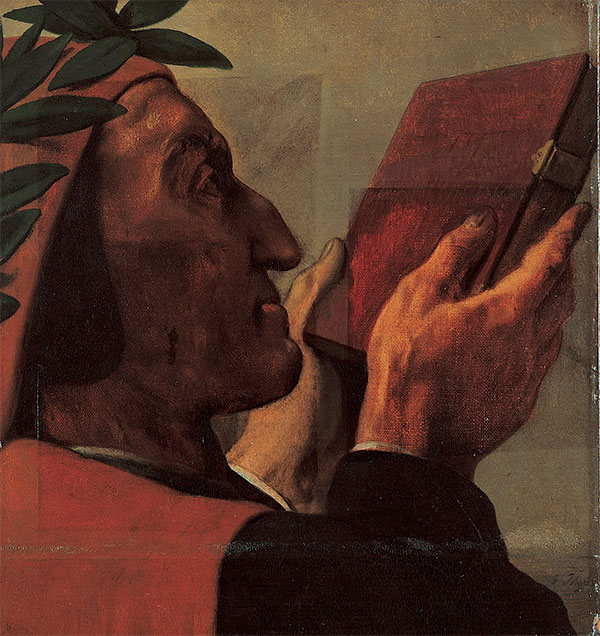

Sketches of Dante and Pindar for Ingres’ allegorical project for the Louvre’s Musée Charles X, “The Apotheosis of Homer”, look dry today, but Degas scooped them up eagerly: they supplied him with a whole repertory of poses, and their fragmentary nature may even have encouraged his daringly cropped, asymmetrical compositions. Also here is a lovely still early Corot, “The Roman Campagna, with the Claudian Aqueduct”, acquired by the National Gallery at the post-1917 sale of Degas’s collection. “A feeling of antiquity survives in the countryside that is wild, empty, cursed like the desert,” Degas wrote of it, yet he also prized this fresh oil on paper landscape painted en plein air in 1826, half a century before Impressionism, for its fluidity and freedom of handling. Degas’ entire collection is a wonderful mirror of the man summed up by his friend Paul Valery as “an uneasy participant in the tragicomedy of modern art, mad about drawing”.

Degas and Matisse transformed art, and as they did so, changed our view of history, making painters of the past seem oddly complicit in the modern endeavour. The 17th- and 18th-century artists here, on the other hand, and the regressive Victorians selected, were not pioneers, and had entirely predictable, reverent tastes in Old Masters. Van Dyck collected Titian. Reynolds acquired Poussin, Rembrandt, Bellini. Lawrence owned a Raphael, a Guido Reni and Agostino Carracci’s 4m charcoal-and-white chalk cartoon “A Woman Borne Off by a Sea God”.

In contrast to the pitch-perfect loans that illuminate the modern galleries, all the examples in these sections are familiar works from the National Gallery’s own collection. As too often in the group shows here, they read like a dispiriting round-up of the usual suspects.

This is, in part, a very good show that declines into a dull one. With more ambition and a modern focus — Picasso and Monet, for example, both of whom had stunning collections — it could have been a great one.

To September 4, nationalgallery.org.uk

Photographs: National Gallery, London; Succession Picasso; Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen

Comments