The Cause: Gavin Turk, Tracey Emin and co auction art for climate crisis

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On an industrial estate in east London – surrounded by rattling vans, beeping horns and screaming sirens – a mountain of scrap metal taller than an electricity pylon is piled high with old washing machines, bent bicycles and rusty cars. Opposite, a cotton flag billows above a silver metal corrugated door. “Climate & Ecological Emergency” it reads, in capital letters. “#CultureTakesAction.” Gavin Turk, the British artist known for his provocative take on waste, flings open the hatch; this garage-like entrance leads to his studio. “We’re in the business of recycling here,” jokes the artist, who has previously turned six overflowing bin bags into an avant-garde sculpture, Pile, and transformed a rotten apple core into a bronze work of art. “A lot of my work is about what we throw away.”

Hung on the wall inside his studio is a black square on canvas, painted using engine fluid salvaged from a white transit van. Titled Motor Oil, 2015-2021, it will be sold at Sotheby’s this month in aid of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), part of a stellar auction running from 8 to 15 October that sees artists including Tracey Emin, Anish Kapoor, Jadé Fadojutimi and Turk come together to raise funds for the non-profit’s 60th anniversary, and ahead of the Cop 26 climate summit in Glasgow this November.

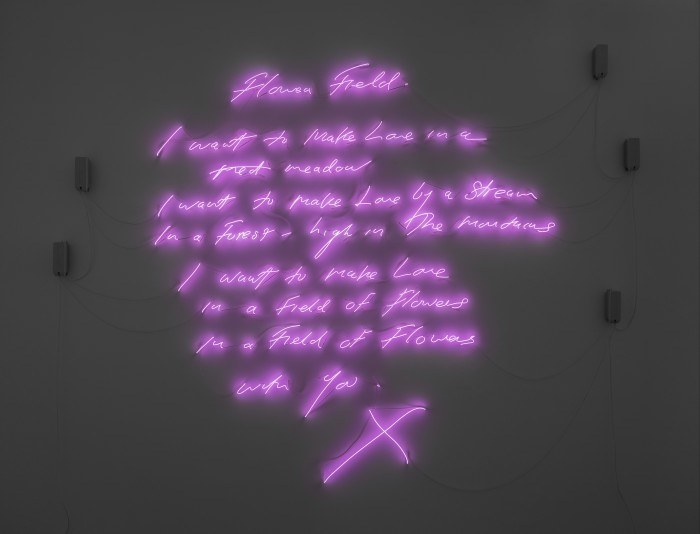

Turk’s concerns about climate change are matched by those of Tracey Emin: “‘There is a giant tidal wave coming down the Thames and it’s going to smash London into matchsticks.” She has donated a neon sign titled Flower Field, 2017 to the fundraising event.

The funds will be used to support WWF’s key international projects, from replanting seagrass – which provides a nursery for fish and sequesters carbon but which is 92 per cent depleted in the UK due to pollution and overfishing – to combating Amazonian deforestation, and implementing tiger conservation programmes. Antonia Gardner, contemporary specialist and deputy director at Sotheby’s, says the auction will “help amplify the mission… For 60 years, WWF has played a major global role on the frontline of the climate emergency. We need to join hands to continue this fight.”

The organisation is known for its work protecting endangered species, but in recent years its focus has been on expanding restoration initiatives – to “put back what’s been lost”, says WWF chief executive Tanya Steele. “Nature is our life support system, but we’re losing a football pitch-sized piece of the Amazon every 12 seconds. The rainforest is our planet’s lungs,” she says. “We need to restore and replant to ensure that species – and we as humans – survive.”

The Sotheby’s auction is part of a broader initiative, Art For Your World, which culminates this November, and includes an online sale of exclusive prints from artists such as Chila Kumari Singh Burman, Heather Phillipson and Bob and Roberta Smith. Burman, the Punjabi-Liverpudlian artist who lit up Tate Britain’s facade with her poignant Remembering a Brave New World neon work last winter, has created prints featuring images of tigers – “a Bangladeshi motif that runs through my work,” she says. Art For Your World will also see a global array of galleries such as Victoria Miro and Hauser & Wirth galvanise their efforts to tackle the climate crisis and address their own carbon footprint. “It creates a ripple effect,” says Ewan Venters, the gallery’s chief executive. “One of our key obligations is to preserve and protect the legacy of our artists and estates… We can’t do that if we’re not taking our responsibility to the environment seriously.”

The art world is notoriously carbon-polluting – works are transported all around the world for fairs, sales and exhibitions. Brett Rogers, director of the Photographer’s Gallery in London, thinks it’s “urgent” that the industry evolves. She also cites the “toxic effects of chemical compounds” used in analogue photography, and the mining of metals for digital photographs (as well as iPhones) that “exploit rare earth materials”, as concerns: “We need to get our house in order.” The gallery is currently commissioning pieces that examine these environmental effects, and encouraging its participants to explore sustainable alternatives, for example to high-resolution image files, which are widely shared via email but come with an oft-overlooked high carbon footprint.

Whether digital or IRL, “the distance between people and things is filled with carbon,” says Turk. He has an “obsession” with unmarked transit vans – and their impact – stemming from seeing continuous pick-ups and deliveries from an Amazon hub nearby; he has even squashed some vehicles into cuboid artworks. “They just go backwards and forwards carrying all this stuff,” he says. He now tries to calculate emission budgets for creating new works, and is looking into hydrogen vehicles to transport them.

Back in his studio, my eye is drawn again to that framed splatter of black engine oil on paper – pollution made visible to the naked eye. Is it oil or an oil painting? Turk laughs. “Artists are always philosophising and proposing ‘what if’s. We’re here to make people think.”

WWF Art For Your World auction, 8–15 October, artforyourworld.com; wwf.org.uk

This article has been corrected to reflect that the non-profit in question is the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and to amend Brett Rogers’ pronouns from “he” to “she”

Comments