Exclusive: Andy Goldsworthy’s epic moorland monument

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is a warm and bright autumn morning when my train pulls out of London King’s Cross. When I alight at Northallerton a couple of hours later, it’s decidedly chilly, with heavy, leaden-grey skies. “This is proper North Yorkshire,” the taxi driver chuckles. By the time I reach the starting point to view the land artwork Hanging Stones, I am truly in another world – grappling with the elements in a landscape that’s part primeval, part outdoor cathedral of art.

Hanging Stones began to take shape about a decade ago, when telecoms tycoon and philanthropist David Ross was approaching what he describes as “a significant birthday” (his 50th). After co-founding Carphone Warehouse in 1989 and building a fortune that has been estimated to exceed £1bn, Ross has since devoted much of his attention and funds to art and music. (He is chair of the board of trustees of the National Portrait Gallery and recently donated £4mn to its renovation; this summer he launches the Nevill Holt Festival on his estate in Leicestershire.) He also owns a considerable amount of property – some 12,000 acres – around Rosedale, a breathtaking valley in Yorkshire. What better way to celebrate a milestone birthday than by commissioning a work of land art here, he thought. His estate is situated within the North York Moors National Park, where miles of public rights of way give hikers wide access; the landscape is dotted with curious stone buildings, most of them abandoned long ago and in various stages of decay, if not outright ruin.

Ross drew up a list of eminent artists to consider for his project; atop it was Andy Goldsworthy. A leading member of the earth art movement who earned his reputation from ephemeral constructions of leaves, twigs, reeds and other transitory items, Goldsworthy is at heart a sculptor whose monumental works are composed from stone and other natural elements. Goldsworthy already has deep connections to Yorkshire: he grew up outside Leeds and for many years his parents lived in Pickering, 10 miles from Rosedale. Its agricultural landscape moulded the 67-year-old artist. “Farming is a very sculptural activity,” he says. “The laying of hedges, the building of walls… this is the source of it all.”

Goldsworthy has completed relatively few projects in the UK. More often he works abroad, particularly the US, where institutions including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Stanford University and the Presidio of San Francisco have kept him busy with commissions. “Goldsworthy is revered as a figure of Thoreau-like purity,” wrote The New York Times. Martha Stewart recently expressed elation via Instagram over news that Goldsworthy was constructing an undulating 1,500ft kerbstone in Bar Harbor, Maine, where she keeps a summer home. “We are all very excited about this project!!!” she wrote.

After Ross contacted him, Goldsworthy conceived a plan to rebuild one of those abandoned buildings as an artwork. After the artist’s interventions, a person opens its door to find a dusky room in which a large charred bough spreads across the ceiling, protruding into the rafters. A soot-covered fireplace seems to be awaiting wood to turn into more smoke. It is at once surreal and earthy. Ross was enormously pleased with what he describes as “Andy’s desire to create an artwork that brought together many strands of what he’s done previously in many different parts of the world”.

With the support of the Ross Foundation, the artist then vastly expanded his initial brief. Goldsworthy proposed Hanging Stones, a single work of art comprising 10 buildings connected by a six-mile circular walk. As Goldsworthy conceived it, the walk is an artery by which people will give life to the buildings. “People are the lifeblood of the work,” he says.

“I love hiking and I love art,” says Ross of Goldsworthy’s proposition. “So this was perfect.”

But it’s been a long process. Goldsworthy laboured on one house at a time. The rugged terrain presented him with “some of the most difficult conditions I’ve worked in anywhere in the world”, he says. “You can’t imagine what it’s like when it’s really wet in winter. It becomes so slippery you can barely stand.” Objections from the North York Moors National Park Authority’s planning committee and Covid restrictions slowed things down further.

Now nine houses are complete (though perhaps it’s a misnomer to call them houses, since none has electricity or mains water or provides a home for anyone). They have been given evocative names such as Sugget Spring, Bogs House and Northdale Head House. When Goldsworthy finishes Heygate Thorns in 2025, Hanging Stones will at last be complete.

Already the project is in a soft opening phase. Slots, booked via hangingstones.org, are limited (an adult ticket costs £10; under-18s and students are free). A confirmation email provides an address to collect a map and a key, which opens the padlocks on all the houses. In possession of these, visitors are responsible for opening and closing the buildings. It is also noted that the walk, which takes most people five to six hours, “is suitable for those who are proficient walkers”.

“It’s a hell of a workout!” art dealer Ivor Braka tells me, “a completely immersive experience” where “the workout is part of the artwork”. On the rainy day he visited, he described an atmosphere of “almost prehistoric mists swirling around” and a seamlessness between art and nature. “You’re not consciously aware of it being an artwork in that there is very much respect for the vernacular traditions of Yorkshire,” he adds. “What’s remarkable is the total harmony and integration of natural forces with the local traditions.”

My own visit has come to pass only after a good deal of conversation with artist and patron – both of whom harbour mixed feelings about publicising the project anywhere. They would like visitors to be able to enter each house without preconceived notions or images in their heads. “Anyone can only see something for the first time once,” says Ross. “I don’t want to give the story away. Something has to be held back; there has to be an element of surprise to it.”

I am fortunate enough to walk with the artist himself, along with Ross and his friends. Before we set out, Goldsworthy gives the background on this now-tranquil area. In the 1800s, the valley thrummed with the chug of locomotives, wagons rumbling and iron being mined. Around 3,000 miners and their families lived and worked here; their ore, shipped to the nearby steel mills, helped build the British Empire. Following the depression in the iron trade, and the closure of mines from 1879 onwards, nature largely reclaimed the valley. But not entirely. Those decaying stone structures have the imprint of those who have been there before. Says the artist: “For me, it’s not a pastoral idyll… It’s not just the bucolic place that the National Park wants to sell it as.”

Over the next six hours, we traverse a multitude of landscapes and elevations. Meadows give way to woodland as we ascend the narrow paths, some of them muddy from the rain that fell the night before. I become increasingly out of breath; Goldsworthy sprints ahead.

As we make our way through the rugged expanses, we come upon a house about every 15 or 20 minutes. After each visit, we recalibrate. A rhythm becomes apparent. As Goldsworthy is quick to point out: “It’s the valley itself, not me, that has set the terms of engagement and created my rationale for Hanging Stones. I like the discipline of working within an existing framework.”

The curiosity that builds as each house comes into view turns into astonishment when the door is unlocked. At Hanging Stone House, an 11-tonne sandstone block hangs elegantly from the ceiling of a rough little room. How does it not come crashing down? There is just enough room for a brave soul to crawl under it to contemplate the matter.

Most of the houses appear plain and compact from outside. Yet there’s a world inside each. Walking into the circular space of Southfield is like entering the belly of a giant tree – the walls are mighty stacked boughs that Goldsworthy collected from windfallen oak trees. They seem like living ligaments.

In Ebenezer, the surfaces glint; it feels at once menacing and glamorous. After my eyes adjust to the dimness, I realise that the walls are lined with taut barbed wire. “This is where iron was produced, so one of the works had to have iron in it,” Goldsworthy explains. The barbed wire was formerly used to fence fields in Yorkshire and Scotland; now it rings this room. “The beauty of iron and the horror of iron,” says Goldsworthy.

At Red House, he has chosen to use iron again – applying ochre collected from the site to its surfaces. It’s a work-in-progress because, while the pigment is permanent, the colour is fugitive. “It’s a living, breathing thing, this red,” says Goldsworthy. “It’s red because of the iron content, like our blood.”

As we continue to scramble upward, blood is indeed pumping. In this exhilarated state, we reach the plateau of the moorland. Bleak and barren, it’s a lunar landscape. At this, the highest – and halfway – point of the walk, a long, low building appears ahead, looking like a welcome refuge. This is Job’s Well. “As legend has it – a legend I greatly encourage – this is where the monks stopped to have a rest,” says Ross as he ushers us in. Wicker baskets await us, packed with flasks of piping-hot tomato soup.

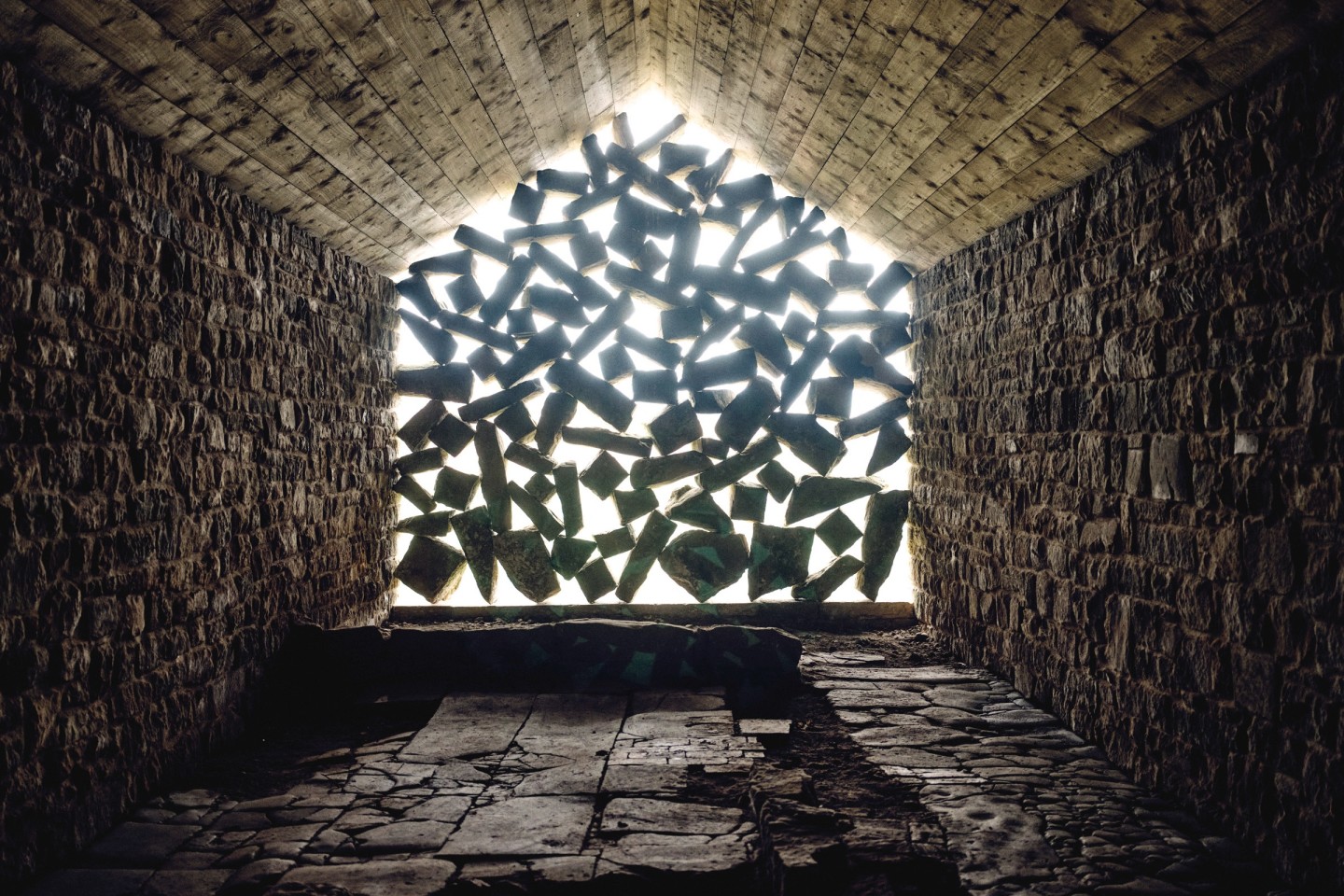

With its oval-shaped, churchlike window cavity, the room inspires a sense of reflection and peace. It also brings a moment for us hikers to pat ourselves on the back for a job well done. The walk downward should be cake, right? In fact, it is challenging in a different way: slippery muddy paths strewn with rocks and branches.

Eventually, after crossing peaty brooks and ground covered with ferns, the environment becomes lush. As the land levels out, there are green pastures with ancient trees, dry stone walls, grazing sheep and wild birds. As if on cue, the sun begins to break through and dispel the clouds. An English Arcadia.

“Walking is a huge gift,” Goldsworthy says. On public rights of way, you meet and chat with people from all walks of life. The US, he notes, would benefit from having more of them. “There’s people who aren’t speaking to each other,” he says. Although Hanging Stones is located on privately owned land, “It’s not at all private,” he says. Still, couldn’t Hanging Stones be seen as a rich man’s trophy? “To some extent. But it’s one that’s open to all.”

As it nears the finishing line, “it continues to grow”, Ross says. “It’s part of an ongoing dialogue that Andy will want to continue in this part of the world.”

“It’s the most important thing I will ever make,” says Goldsworthy. “To have had the opportunity to work in a place that means so much to me has been a gift.”

Comments