Your most pressing sleep questions, answered

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

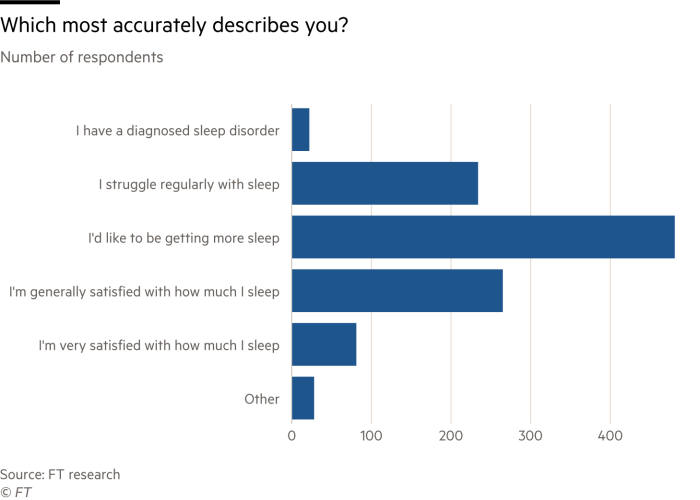

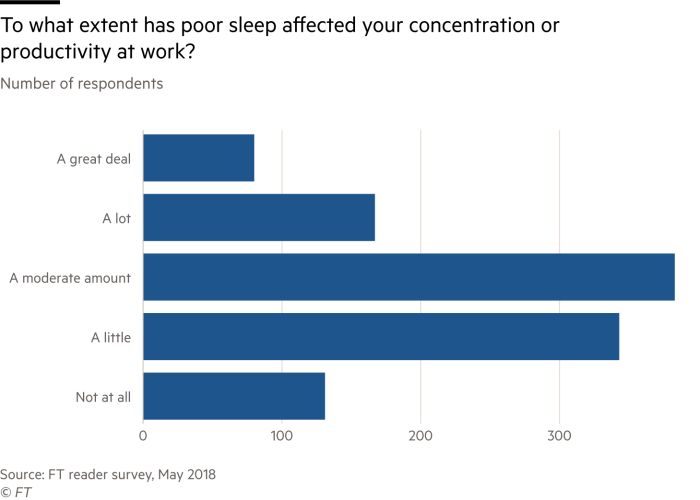

Ahead of this special issue, we put out a call to readers to tell us how well you sleep at night. More than 1,000 of you responded, with stories, questions and ideas for what we should cover. “I have had difficulty sleeping for as long as I can remember,” wrote a reader named Heather, from Cheshire. “I’ve learned to live with it, but I don’t think it has been good for me. I think I could have achieved more in my life and work had I been able to sleep better.”

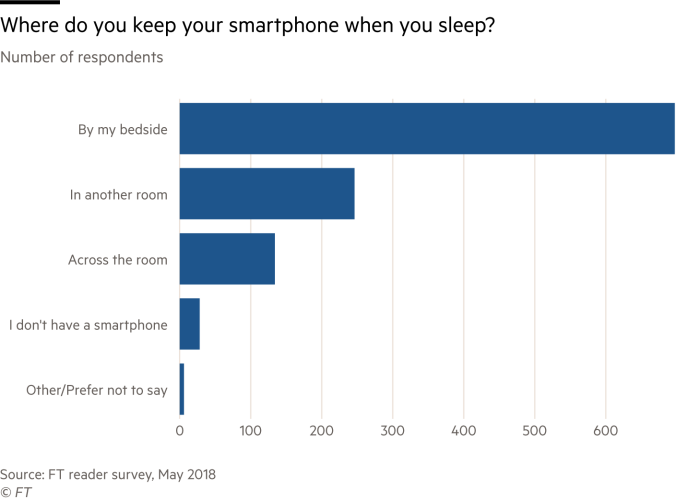

We’ve collated some of the survey results here (see charts below), and we also took a selection of your most pressing and common questions to two doctors dedicated to helping patients get a good night’s sleep. Dr Jason Ong, PhD, is a psychologist and associate professor of neurology at Northwestern University. He specialises in using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to treat insomnia.

Dr Sara Benjamin, MD, is a clinical associate who evaluates patients for sleep disorders at the Sleep Center at Johns Hopkins University. Their answers have been edited for clarity and length.

Q: “Does the light from a tablet or smartphone really stop you from sleeping effectively?” — Gordon Rorrison, Aberdeen, Scotland

Dr Ong: In general, the light from your screen can affect your circadian rhythms. Using light later at night suppresses the release of melatonin. Once melatonin gets released, your brain starts preparing for sleep. Is it better to put your phone aside or in another room? Yes, under that principle. Any temptation to keep your brain stimulated is just going to make your brain think it should be awake.

Beyond that, it depends on what you’re doing. If you’re checking the global markets on your iPad, you’re engaged. Your brain will think you should be awake. If you do something that makes your brain think you should be awake, your chances of sleeping aren’t great.

Q: “Even when I go to bed early, I still can’t fall asleep until around midnight. What is the best way for someone to find out how much hours of sleep they need?” — Maria Sotiriadou, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Dr Benjamin: If you have a week off, try sleeping without an alarm — after you make up your initial sleep, see how much sleep you get. That will give you some idea of what you need to feel your best. You can also use that time off to chart your natural sleep and wake time.

Q: “What methods can you recommend to make the overactive mind fall asleep? I’d like more ideas than the usual suggestions for low light and calm activities in the hours before sleep.” — Jesse Sloane, Seoul, South Korea

Dr Ong: For insomnia, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the gold standard treatment. The first thing I tell patients to do is set aside some structured worry time. It sounds counterintuitive if you’re already worrying, but worry tends to find us. This technique is based on principles of exposure: rather than trying to get rid of your worries, let it out.

It makes it less likely to come out at other times, such as when you’re lying in bed. You can use a disclosure method like writing your worries down to help you get them off your chest. We usually tell people to do this at least an hour before your bedtime. I tend to do it right before I leave work, so I can come home in a different mindset.

The other option comes from the Buddhist concept of mindfulness. The approach there is a little different: it’s not to get rid of your thoughts, but have a different relationship with them. The analogy I like to use is trainspotting: trainspotters don’t use trains for transportation, they just stand on a platform and watch them go by. They observe.

If our thoughts are like trains, mindfulness is to be a trainspotter of the mind. It’s a metacognitive technique: sit on the platform and watch your thoughts and concerns go by, without feeling like you have to do something about them. As you practice this, usually you’ll see that thoughts that were once so important begin to feel less intense.

Q: “How can I not be stressed as I watch the clock tick away and eat into my precious hours of sleep?” — Anonymous, London

Dr Ong: Take the clock away, so you’re not tempted to look at it. The more you look at it, the more you’ll feel pressure. Think of your time in bed as a window of opportunity for sleep, versus a schedule. You want to protect that window by trying to avoid things that aren’t sleep promoting, like looking at a clock. That clock is just going to make you more anxious.

Many people think, ‘I need to go to bed at this time, and wake up at this time.’ But going to bed at the same time every single night isn’t necessarily helpful. It puts too much pressure on you. Sometimes you’re not sleepy. Thinking of that time as a window of opportunity for sleep gives people some flexibility.

Q: “As a relatively new parent (one three year old and one six months old, neither of whom sleep well!) I’m interested in how people balance the sleep deprivation that comes with young children and managing a demanding profession.” — Elliott Scott, Chester, England

Dr Ong: I have an 11 month old. It’s tough. That’s part of parenting. My advice is just to change your expectations. The effects of acute sleep deprivation are recoverable. It’s chronic sleep deprivation that can have longer term consequences. Where that threshold is drawn can’t be answered very definitively. But for generations, humans have lived through sleep deprivation from parenting and we’re still around. So I wouldn’t worry too much.

Q: “I used to be chronically sleep deprived. I’d get up at 5am to catch the 6am train to NYC. I’d work like a dog as president of a Madison Avenue communications company and get home by about 8pm. We’d have dinner at 9pm and go to sleep by 11:30pm. That meant I was only getting five and a half hours of sleep a night when I know I function best with eight. What health implications did all those years of sleep deprivation have?” — Daria Blackwell, Westport, Ireland

Dr Ong: There’s more and more evidence that suggests that long term sleep deprivation can have some health consequences. But we just don’t know what causes it and whether it’s reversible yet. As a field, we are doing those studies now. Hopefully in the next five years or so we can provide a more compelling answer to that question.

Dr Benjamin: If that period of sleep deprivation is over now and you’ve already recovered your sleep, it won’t help you to worry about it. I would just move forward and try to get the best quality of sleep that you can.

Q: “I’m curious about the difference between owls and larks: is there really a health problem with being an owl? Why?” — Stephen Wright, Ingleton, UK

Dr Ong: This is about our natural circadian rhythms. I try to set a sleep window for patients that is as conductive as possible to the person’s circadian rhythms while also considering their schedule. You can adjust your circadian rhythm, as you can adjust for time zones when you travel. But since you’re going against your natural tendency, it takes a little more discipline and consistency to stay at that place.

For night owls, it’s best to regulate your wake up time and your exposure to light at night. Morning types can get sleepy too early, then wake up at 3am. So for them, we encourage more exposure to light at night to delay their bedtime.

Dr Benjamin: If you can, it’s best to try to find work that matches your tendencies. For people who really have true “delayed sleep phase”, if they’re in a job that starts early in the morning, it will be a constant struggle. I think some of my patients who are successful and naturally night owls have found careers which allow them to work the later shifts.

For people who have delayed sleep phase, the idea would be to turn off your computer earlier or change the settings, and have more light in the morning — opening the blinds and letting light in when you need to get up.

Q: “Why does it seem that as we age, we find it harder to get enough quality sleep?” — S Hobley, Birmingham, UK

Dr Benjamin: Many of my patients worry about this. But less deep sleep is a normal part of aging. It is more profound for men than for women, although women can be disrupted by the effects of menopause. Keep in mind that sleep disorders like sleep apnea and restless leg syndrome also become much more prevalent as you get older. So it’s worth seeing a doctor and getting screened if you’re struggling.

Just do your best: make sure you’re in an environment conducive to sleep, and keep yourself physically active. If you exercise to the point that you’re hot, the rise and fall of your body temperature during the day will help you sleep better at night.

Q: “Can some of the most successful people really live off just four to six hours of sleep?” — Patrick, Frankfurt

Dr Benjamin: There are some people who do very well with very little sleep. Most people aren’t like that. A lot of people are used to being chronically sleep deprived, and compensate with caffeine or short involuntary naps. So not everyone who gets that little sleep is really at their best. If they did performance tests, they might realise that they’re not performing as well as they could.

Dr Ong: There are successful people and there are people who live off of four to six hours of sleep. They’re usually not the same people. Think about it as a bell shaped curve. The average is between seven and eight. It’s possible to be in the tails of that curve and be fine. But once you get below six, you run a greater risk of having issues. The best way to know is whether you’re sleepy during the day. Are you falling asleep unintentionally? Are you having trouble concentrating? That’s a pretty clear sign that you’re not getting sufficient sleep.

Lilah Raptopoulos is the FT’s community editor

Illustrations by Lucas Varela

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments