‘I am here. I’m alive.’ Tracey Emin on health, wealth and finding happiness

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Most interviews start with a cursory “How are you?” – but with Tracey Emin, this has an extra heft. The esteemed British artist, now 58, purveyor of beds, tents, neons and paintings that have graphically recounted her life experiences, might always be relied on to give you an intense answer; but now especially so considering the past two years she’s had. In spring 2020 Emin was diagnosed with squamous cell bladder cancer, a particularly aggressive strand of the disease that led to surgery in which she had her bladder, her urethra, her lymph nodes, her womb and half her vagina removed. At the time, interviews she gave suggested she would struggle to get past Christmas. So – how is she?

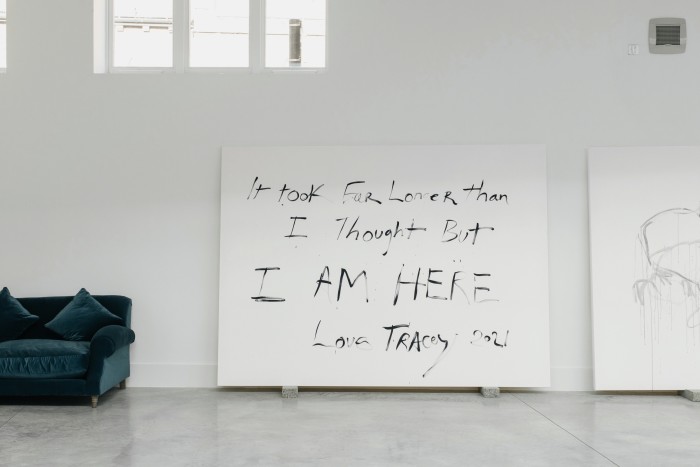

“I wrote a list of things earlier,” she confides in her sing-song voice, her Kent vowels still strong despite first leaving her native Margate more than 40 years ago; she’s calling from her home there now. “My list of really positive things was: ‘I am here. I am alive.’” Emin has been given the all-clear. “I just had my big check-up last week with my surgeon, and it’s amazing – I don’t have to go back now for six months. So I’m moving fast away from cancer, I’m shifting.” But she is still prone to huge waves of fatigue.

Despite this, she is very eager to talk to the FT, specifically How To Spend It. “This is how to spend it!” she says gleefully, and it turns out she has all kinds of personal and political reasons for doing so. She has certainly earned it: against all expectations she made it as one of Britain’s most important living artists, moving from notoriety as one of the YBAs to gaining a teaching position at the Royal Academy, a stint doing the British Pavilion at Venice Biennale and a CBE. Right now, in Oslo, a huge show places her in tandem with her hero, Edvard Munch; Queen Sonja of Norway, a fan, came to the opening dinner. And it’s no push to say that she’s currently in a big phase of regeneration – not just for herself but for Margate, which may come as a surprise. This is the seaside town, after all, where she had such a troubled early life (leaving school at 13, rape, suicide attempts and more), and to which you might never have expected her to return – except that she has, in some style.

Five years ago, Emin bought a huge complex of buildings near the seafront with her close friend (and ex‑partner) the gallerist Carl Freedman; he turned his half into a gallery, she turned hers into an exquisitely turned-out studio and apartment complex, complete with archive spaces, roof garden and stunning baby-blue‑tiled pool. When she dies, all this will become an Emin museum and archive. I had read somewhere it would almost be a mausoleum, but she scratches that: “I don’t think that would be allowed.” She would rather, she says, her ashes were eventually in some “plinth thing”, alongside those of her mother, who died a few years ago, and Docket, her late and equally beloved cat.

“Have you ever been to Moscow, where you walk past Lenin’s body?” she asks suddenly. Umm, no. “You have to walk around it in silence.” She gives a naughty chuckle. “I always thought, that’s pretty cool…”

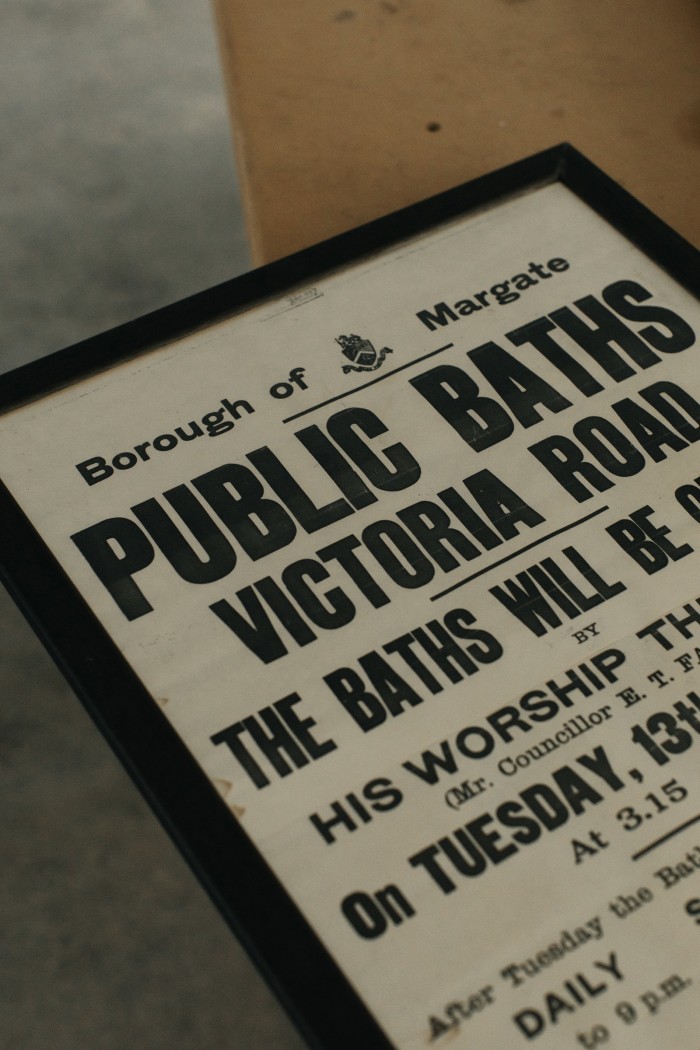

All that was just phase one: she is now itching to reveal that she has bought yet more property in the rapidly gentrifying Margate, a whole compound five minutes down the road that includes former Victorian baths and a small morgue, which will be turned into dozens of artists’ studios and another mini Emin museum. The Tracey Emin Foundation, all run as a non-profit, will also provide a sculpture park, artist residencies, lectures and, crucially, a life-drawing club, so that “any kid in the area who wants to come in and learn to draw, can”. There was none of this for her, growing up. And on top of all that, she’s pledged £100,000 to a bid for Margate to have its own Olympic Skate Park, which she is equally evangelical about. It all seems inspired, engaged and overwhelmingly generous – in other words, deeply Emin.

“It’s almost like I’ve had a sabbatical,” she says of her period of illness. “Time to sit back and think: what is it all about? Why am I an artist? What am I doing? What’s it for? And… I’ve suddenly worked out what it’s for! I know what I’m doing. I want my art to make people’s lives better.”

I spoke to Emin twice: first, for a long time on the phone; second, a week later, when she invited me to Margate. She promises she is calmer, much more still now, and this does seem true. (Although, this being Emin, drama is never far behind: “I nearly burned my house down yesterday,” she sighs; she fell asleep while making chicken stock.) She is alternately defiant and defensive about what she chooses to do with her wealth.

“It’s my money, and it’s what I want to spend it on,” she says firmly. “I’ve worked for it, I’ve worked really hard, and I’ve paid back to society.” She is talking about it now, she says, to encourage others to do the same. She gives to an absolute plethora of charities – Terrence Higgins Trust, Oasis, Centrepoint, the Elton John AIDS Foundation and more – and started doing so even as a student. “I realised, with my friend Maria, that we spent as much money per week on biscuits as it would to be a member of Amnesty International, and I’ve been a member ever since.”

And she has always been good with money. It’s how she manages to not only have all this Margate property but a home in the south of France and, just recently, a gorgeous Georgian townhouse on London’s Fitzroy Square. “As an artist, you’re not supposed to admit that, because being good with money means you’re not creative, you’re not spiritual,” she tuts. But that’s nonsense. “The reason I have been brilliant with money is that, in the 1990s, I never took cocaine. Ever. I think I saved the same amount of money to buy my first house as most people back then were putting up their noses.”

Other things on which Emin likes to spend it: her two pedigree kittens, Teacup and Pancake, now eight months old, who replaced the much-mourned Docket; psychics and tarot readings (she prefers that to therapy); shopping in Margate’s cult antique shop, Scott’s; Vivienne Westwood dresses and Patrick Naggar furniture. Art by young emerging artists. An electric car to scoot around town, and a hired BMW and chauffeur for other things – as she points out, public transport is a nightmare now that she has a urostomy bag. A holiday she’s about to take in Thailand, her first in 10 years because she’s a “workaholic”, although she has, over the years, checked in regularly to Austria’s VivaMeyr clinic for its treatments. Antique rings – she’ll buy herself one every time she does a show – “but I have to have done a good show, and I have to have worked hard, and I have to have sold work.” She also very nearly bought a 20-inch antique Egyptian cat at Frieze Masters last October, but finally met her limit. “I was like, it’s amazing, it’s brilliant, I’m gonna get it,” she recalls. “My nose was almost touching it. I asked, how much is it?’’ £2.7 million. “I said, riiiiight, I can’t afford that.” A tiny pause. “Well, actually, I can!”

The gifts to Margate, though, have a whole other depth. Emin admits that even 10 years ago she would never have imagined she’d be back there. Mind you, she is quite down on middle-aged Tracey in general, who “got distracted by crap”, she sighs sadly. “Drinking… poncing around.” (She doesn’t drink now: “I think a bottle of wine would kill me.”) But all this change was afoot well before her diagnosis. It was a few years ago that she decided to sell her home and studio in Spitalfields, where she’d been for decades, in order to buy in Fitzroy Square. Selling up was “amazing – life-releasing”, she promises. “Like an epiphany.” She thinks it’s that mindset that helped her when the cancer then kicked in. “I had the confidence to change my life. Because you just accept the status quo – you just go, ‘This is my life, I’ve got to get on with it.’ Well, actually, if you’re in a position to change it, you should. Because there’s a hell of a lot of people out there that can’t!”

In Margate, I’m met first by her friend Robert Diament, director of the neighbouring Carl Freedman outpost. He shows me her beautiful airy white studios, with its large canvases propped against the wall; in one sombre female silhouette, you can make out an attached urostomy bag. Upstairs in a mezzanine is a gigantic archive of prints, posters and photos from Emin’s wilder days. Diament only moved to Margate recently but is a rabid convert. He thinks Emin’s project is just what the town needs. “It’s probably going to attract artists from other cities where maybe it’s too expensive to live now, and getting studio space is so hard,” he says.

Emin has ended up here far more than even she expected, he confirms. “I think she’s really, really happy to see Margate coming alive. She already had a kind of fire for it in her heart. It’s a very romantic love in a way, because I think it was a very special place for her to grow up, in spite of the challenges and hardship that she experienced. I think there was always a sense of hope here.” Jay Jopling, White Cube founder and Emin’s gallerist of decades, confirms that this is an exciting time. “She has never flinched from looking at the world with absolute honesty,” he says. “We look forward with great anticipation to seeing how her recent brush with mortality might have affected what she chooses to share with the world.”

Next door to Emin’s studio in her adjoining flat, all whites and greys and perfectly placed small artworks, I encounter Teacup and Pancake making havoc in Emin’s bedroom. Eventually Emin herself emerges, wrapped in a towel, from a few laps in that blue pool. If a lot of Emin’s work seems to deal with excess, everything in her home is just-so. She quickly gets dressed, puts on a black skirt and jumper, small bits of delicate gold jewellery and some sturdy black Chanel Coco Neige boots, and we all traipse to her favourite fish restaurant, Dory’s, before they show me the baths and the morgue. Emin wants the renovations to be completed “as soon as possible. Hopefully everything” – the studios, the mini museum, the Foundation – “will be up and running [in the] next year.” On one hand, she keeps saying she is luxuriating in all this extra time she’s been given; on the other, there is an urgency to enjoy.

“It’s like I’ve got some enthusiasm for living,” she admits. “Because before I was ill, I didn’t. Honestly, I just felt like I was dying all the time. So now I don’t have that thing in me – that darkness. It’s gone.” She still has moments of despair or fury, but she knows how to channel her energy better. “How to spend it? Don’t spend it on getting angry!”

As Emin’s mother lay dying, she said something heart-breaking to her: “‘I don’t want to leave you on your own.’” But Emin doesn’t mind being alone now – or she is as alone as she wants to be. “Art is my driving force,” she announces. “I am singular; I live singularly. I don’t have a family, I don’t have a partner, I don’t deal with the world how most people do… I am just my own entity.” Is that her more natural state? “Yeah, I think so. Because I need time – I need to be alone and to think a lot, to make my work and to understand what I’m doing.” She says that she became broody recently; not to become a mother, but a grandmother. “Much more interesting,” she laughs. But then, serious again: “I’m not a mother. I’ve never been a mother and never will be a mother. But I am, with my art.”

The gifts to Margate are, quite simply, her descendants. Later on, I’m reminded of how she vividly described the town while raving about its possibilities – a place, she said happily, stuck between this “hardcore roughness and these huge 30-foot waves”. It’s hard to think of her anywhere else.

Comments