The world has the capacity but lacks the political will to manage migration

Simply sign up to the Global migration myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

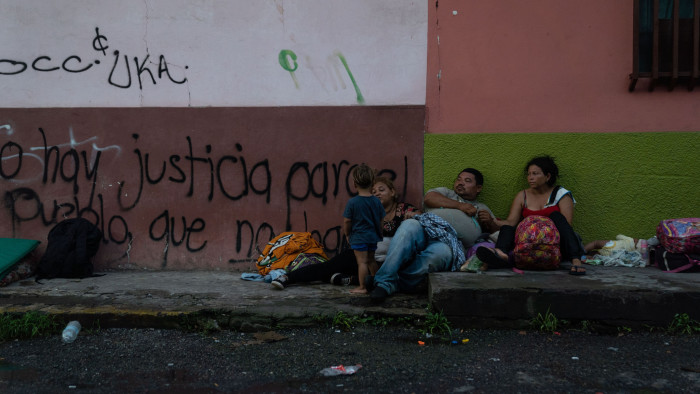

“We don’t have money for food. We don’t have money to call home. We’re nobodies.” Newly released from an immigration detention centre in southern Mexico, Maribel Hernández chokes back tears.

It is no surprise she is migrating. In Honduras, her home, virtually every second adult wants to leave the country, according to pollster Gallup. Most head for the US and many seek asylum — not because they necessarily qualify but because turning yourself in at the border is safer and cheaper than paying a smuggler to get across.

But then President Donald Trump slashed their legal avenues and laid down a challenge over whether the concept of asylum, enshrined in the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, needed to be rethought for the 21st century.

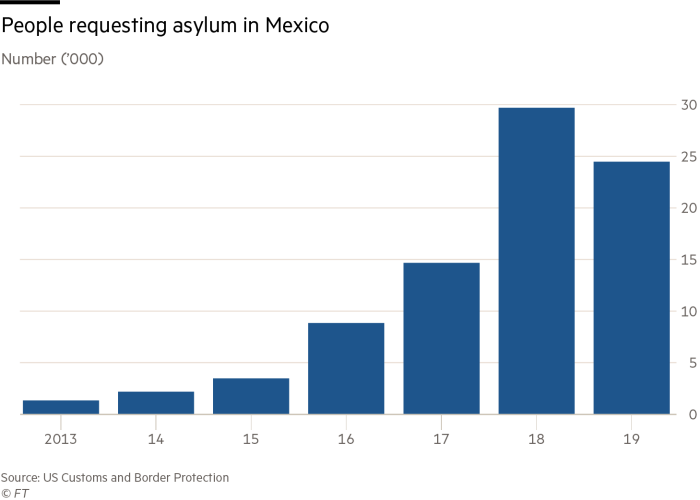

Mexico has become the front-line of deterrence after Washington threatened export tariffs unless it slashed migrant flows across its territory. As a result, seeking asylum in Mexico has become a strategy for some.

After being detained in Palenque, near the Guatemalan border, Ms Hernández, a 25-year-old single mother, has weighed her options. “We decided to ask for asylum in Mexico so they wouldn’t deport us,” she said.

Her reasoning goes like this: if she can get asylum, she will be able to travel through Mexico without fear of deportation. If she can make it to the US, she will. If not, her Plan B is to head for Mexico’s industrial capital of Monterrey, where she thinks there are more — and better paid — jobs for migrants.

Asylum is a growing worldwide phenomenon and, in the US, a white-hot political issue. Around the world, from 1.3m Rohingya who fled Myanmar to more than 4m Venezuelans flooding abroad, the UN estimates that one person is forcibly displaced every two seconds. With the highest displacement of people on record, there are 26m refugees globally, as well as 3.5m asylum seekers, the UN’s refugee agency says.

But a lot of migrants from the so-called Northern Triangle of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, where more than two-thirds of people live in poverty, do not qualify according to the UN declaration, which enshrines the right to refuge from persecution.

Many are fleeing gang violence or extortion. But hundreds of thousands of others, such as Ms Hernández, are forced out by extreme hardship or climate change.

“This distinction between ‘economic migrants’ and refugees . . . is how our laws are structured, but it so does not reflect reality, because you can’t stay [at home] if you are hungry,” said Stephanie Leutert, an immigration expert at the University of Texas.

The concept was updated with last year’s UN global deal on migration that is designed to share responsibility, but the US did not sign. “The tragedy here is the world has the capacity to effectively manage these challenges . . . but not the political will,” said Eric Schwartz, president of Refugees International.

“You need to have a comprehensive approach: protection for refugees, but also other pathways, for example to address migration driven by economic factors or family reunification,” said Mark Manly, head of the UN’s refugee agency in Mexico.

Ms Hernández is from a remote island that relies on fishing, but fish stocks are dwindling so “there’s no income, no work”. She has two children and is pregnant, after being raped, and needs to support her family in a country that offers no social safety net.

Maureen Meyer at the Washington Office on Latin America think-tank said: “In Central America, [asylum] is not always directly linked to state repression, it’s more about the inability of states to protect people.”

With many enforced migrants trying to cram into the narrowly defined asylum category, Mr Trump has tried to shift the burden to his southern neighbours.

A migrant clampdown in Mexico has reduced the number apprehended at the US border by more than half since May. Washington is also pushing Guatemala and Honduras to become so-called safe third countries, where asylum-seekers would be obliged to seek refuge instead of pressing on to the US.

“This administration wants to narrow access to those who can already fly in on a visa,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick at the American Immigration Council. Last year, Mexico’s president Andrés Manuel López Obrador welcomed migrants with the offer of humanitarian visas but was overwhelmed and had to backtrack.

Mexico is now championing development plans for the Northern Triangle to address the root causes of migration, including offering stipends for apprenticeships and rolling out a tree-planting programme. But experts say the poorest are not always those who leave and that having an income can perversely make some more able to migrate.

But with Mexico on the front line as asylum avenues close in the US, the UN’s refugee agency is trying a different tack: moving migrants to Mexican cities where there are labour shortages so that they contribute to the economy and are not stuck in limbo.

“We need to focus on finding other solutions and until people can go home safely. That means supporting labour market integration and access to national services,” said Mr Manly. “It’s in countries’ self-interest to take a different approach.”

Comments