Why ‘buy, borrow, die’ tax strategy could become ‘buy, borrow, pray’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Nominated twice in the Quotes of 2022 Awards, for Understatement of the Year and Stock Market Quote of the Year, here is how Peloton founder John Foley described the collapse of his fortune and the scramble to deal with loans he took out against his stake in the fitness group: “This was not a fun personal balance sheet reset.”

As Peloton’s share price has slumped, Foley’s ugly personal finances have become a preoccupation of the media here in the US. In March, the New York Post noted he had put his $55mn Hamptons home up for sale at a loss, weeks after buying it. Later that month, Business Insider reported he was in talks with Goldman Sachs to restructure his loans, after Peloton stock had lost three-quarters of its value. It has lost another three-quarters since then and Forbes magazine, which counts up rich people, has booted Foley off its billionaires list.

And it was in October, just after Foley quit the board of Peloton, that The Wall Street Journal elicited the “balance sheet reset” remark, for a report that Foley had faced repeated margin calls from Goldman. His resignation means he is free to pledge more shares as collateral, or to sell them. He didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article.

My interest in his story stems not from our sharing a last name (he is no relation) but from it being a timely cautionary tale. Global stock markets lost about a quarter of their value in the first three quarters of 2022. But once-hot pandemic-era stocks, like Peloton, as well as recently floated tech shares and fads such as Spacs (special purpose acquisition companies), have suffered much larger declines.

For the wealthy living off loans against their stock instead of selling it for income — something that appears to have been a popular capital gains tax avoidance strategy — these are frightening times.

A huge leak of tax filings in the US last year, obtained by the non-profit media outlet ProPublica, threw a spotlight on many different strategies used by billionaires to avoid paying taxes, but none caught the imagination so much as “buy, borrow, die”. It sparked new calls for a wealth tax to complement taxes on income that the wealthy turn out to be adept at avoiding.

Under the “buy, borrow, die” strategy, a government may never get to tax the capital gains on an asset. Wealthy individuals, during their lifetimes, borrow against their stock holdings instead of selling them, and then bequeath them to children, for whom the capital gains basis is revised up to market value at the point of inheritance.

Of course, that only works if you can meet margin calls — the demand for extra collateral that comes when the stock price goes down. If you have to sell the stock, you can quickly enter a downward spiral, especially if you have such a significant stake that your selling puts further price pressure on the stock.

This is the reason Peloton’s securities filings this year included a warning that several early executives had pledged their shares for loans (and presumably why the company has now banned executives from borrowing against their stock entirely).

It is also why, at tech group Oracle, where founder Larry Ellison has pledged 307mn of his shares to fund his outside business interests, a board committee regularly checks to see if he has other means to fund margin calls.

And it is why lenders are not going to let anyone borrow as much against a single, volatile stock as they will against a diversified portfolio.

When Elon Musk originally proposed using a margin loan against his Tesla stock to fund his bid for Twitter, the loan-to-value was 20 per cent — that is, he had to put up $62.5bn of Tesla shares to secure $12.5bn in financing. It was the first part of the financing package he replaced when other backers came in.

I wrote here, last year, how the ProPublica articles were effectively a “how to” guide for wealth managers and, sure enough, financial advisers threw up blog posts offering to help clients emulate the very rich.

Arguably, given this year’s stock market plunge and the discovery that some people are overextended, it may be more appropriate to rename the strategy “buy, borrow, pray”.

Regulators have, on occasion, expressed alarm as securities-backed lending has spread in recent years. In the US, Finra highlighted the risks of securities-backed lines of credit (SBLOCs), which can allow clients to borrow up to 75 per cent of the value of a diversified equity portfolio.

Tom Anderson, a wealth management consultant in Chicago, likes to point to the great bear market of 2008 for a simplified example showing the danger of leverage. His recommendation is that people don’t borrow more than 25 per cent of the value of the portfolio they are using as collateral. “If you had a $1mn portfolio and borrowed at a 25 per cent loan-to-value, when the market fell by 50 per cent, nothing happened to you,” he says. “If you borrowed at a 50 per cent LTV and the market went down 50 per cent, you were wiped out.”

But banks are not always highly incentivised to protect borrowers from themselves. Because SBLOCs are collateralised by securities that can be easily seized and sold, they are treated as low-risk by regulators, making them an attractive form of lending.

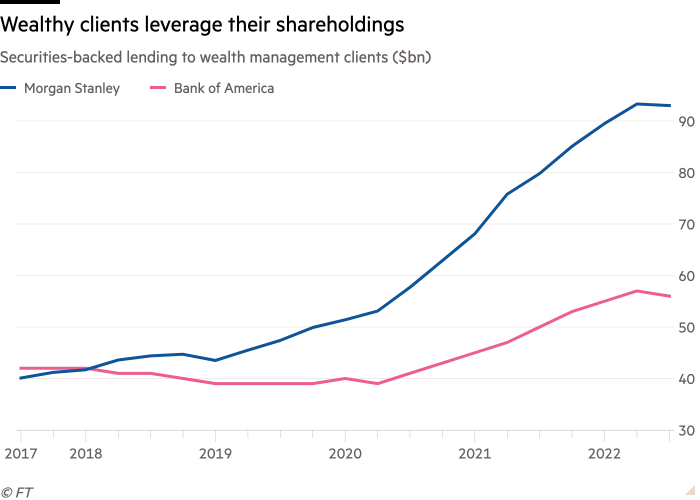

Analysts have, therefore, been unsurprised at the significant growth of securities-backed lending. At Bank of America’s wealth and investment management arm, which includes the brokerage Merrill Lynch, it rose 50 per cent in the three years to June 2022. At Morgan Stanley, it doubled over the same period.

It is only in the most recent quarter that is has plateaued, at $56bn at BofA and $93bn at Morgan Stanley. It is an open question whether this means clients and their advisers have pulled in their horns because of the market volatility. It may be that rising interest rates have simply encouraged clients to shop around. Lower rates are often available on securities-backed lending products offered through smaller brokers. And those rates remain highly attractive versus other forms of borrowing.

“The ‘buy, borrow, die’ strategy still works,” says Sharon Winsmith, a New York-based tax adviser, “if you know what you’re doing.” She describes borrowing against publicly traded securities as an opportunity to “double dip” — to cash in an investment and put the money to use elsewhere, while keeping the dividends and capital appreciation of the original investment.

“To the extent that I took on debt through Goldman, it was because I am bullish on Peloton and still am,” Foley explained last month.

Of course, the market sharply disagrees with him and Peloton shares still languish, at least for the time being. And therein lies the lesson: if your tax planning hinges on a bull market in equities, you can quickly find yourself in a world of pain.

As Foley went on to say: “Everyone can see I had a rocky year.”

Follow Stephen on Twitter @StephenFoley

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments