How the UK got coronavirus testing wrong | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the second week of February, as Britons awoke to news that the number of people infected with coronavirus in the UK had risen to nine, their health department offered some words of reassurance.

“The NHS and wider health system is extremely well prepared for coronavirus and follows tried and tested procedures of the highest standards to protect staff, patients and the public,” it said.

Six weeks later, that certainty has been shattered.

Ministers are struggling to convince a locked-down country with more than 14,550 confirmed cases and at least 759 deaths that they can ramp up the numbers of ventilators, hospital beds and the one measure many experts say could have helped to thwart the crisis in the first place: tests.

“Testing is the basis of public health detective work to shut down an epidemic,” said Professor Anthony Costello of University College London, a former director at the World Health Organisation.

He added that tests were vital for tracking down people with symptoms, identifying their contacts and quarantining them all until they were no longer infectious.

Other experts said that knowing how and where cases were spreading also helped to guide authorities on what sorts of measures to use in response.

At first, it seemed that the UK was going to follow this approach. But the steps it took next have become a source of concern for an anxious public and National Health Service workers on the front lines of the outbreak.

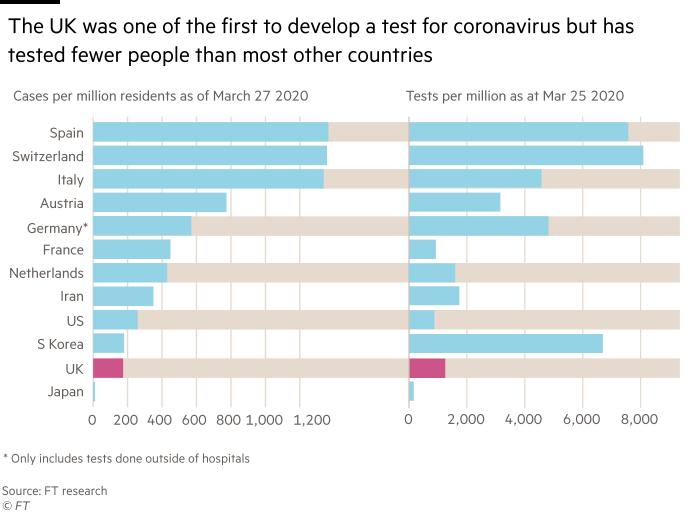

When China released the coronavirus genetic code on January 12 — a blueprint for producing tests — the UK became one of the first countries to develop an accurate test for the presence of the virus in patients.

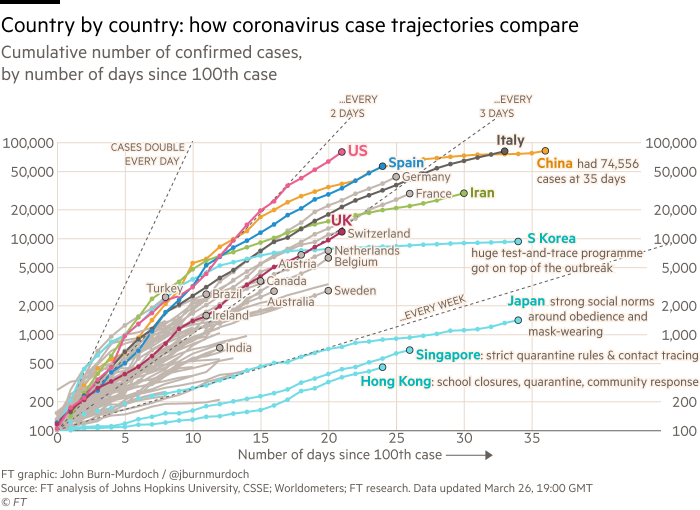

Britain quickly began to track down and trace potential carriers, but it did not follow the much-praised path of mass testing in South Korea, which was soon testing more than 10,000 people a day.

Britain also processed its tests in a different way to South Korea and other countries. Instead of using a network of public and private laboratories, the UK initially used just one lab — Public Health England’s Colindale facility in north London, which was processing about 500 tests a day this week.

As coronavirus began to spread around the world, the UK gradually enlisted more labs across the country, announcing on March 11 that it had carried out 25,000 tests in total and was aiming for 10,000 a day — a target it has yet to reach.

That sequential approach was “very unsatisfactory”, said Greg Clark, the former Conservative business secretary who chairs the House of Commons science select committee, which is investigating the government’s response to Covid-19.

“First there was one PHE lab [Colindale] testing, then 11 others joined in and eventually more labs in the NHS and universities were involved,” he said, adding: “Why were they not all started in parallel?”

Some experts believe bureaucratic fiefdoms might explain why the Colindale lab was only gradually joined by others. “If I’m running a lab where every sample of a really interesting new disease has to come to me for testing, then I am in control of the data,” said one senior academic who has worked in many UK laboratories.

“In that situation, it’s a bit difficult to think ‘We need a network of places and it doesn’t matter where the tests are done as long as all the data come together’.”

PHE said: “The rollout to other parts of the UK is the fastest deployment of a novel test to PHE and NHS labs in recent history, including in the swine flu pandemic in 2009.”

The agency added: “The rollout of additional capacity requires properly trained staff, equipment and a supply of consumables as well as a thorough validation process for the lab to ensure the results are correct.”

“Accuracy is especially important given the PHE and NHS laboratory capacity is focused on testing the most vulnerable patients in ICUs [intensive care units], for whom the result will influence vital clinical management and infection prevention and control decisions.”

However, Mr Clark criticised the UK for not learning more from the experiences of other countries. Germany, for example, has had a relatively low coronavirus death rate after boosting testing to a reported average of 500,000 a week — about 12 times the number carried out in the UK.

“There has been no public explanation of the rationale for the UK taking a different approach,” said Mr Clark, who added he had been asking Matt Hancock — the health secretary who on Friday said he had tested positive for the virus — to explain the UK’s divergent strategy for nearly a month.

“At every point he has been ambitious for an increase in testing but what we have found is that the rate of increase has been very slow. Even now we’re at 6,000 tests per day, which is scarcely a transformation. It means just 10 tests a day in every parliamentary constituency,” he said.

Some politicians believe there was never much of an appetite for aggressive testing in the UK. “There is a belief here that the things being done in Korea were too intrusive and wouldn’t be acceptable,” said one senior Tory. “No one believed you could be totalitarian about this.”

The Tory added: “But what’s actually happened is China, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore — all countries that have a memory of Sars — did much better than anyone thought. It must be the case that we have paid a far bigger economic price from our strategy.”

Adding to the confusion, as the number of UK infection cases has risen, the government’s testing strategy has repeatedly shifted.

On March 14, officials signalled the contact-and-trace strategy for fighting the spread of the virus was ending, except for those in high-risk places like prisons or care homes. For everyone else, testing would be prioritised for those most ill in hospital.

Within days thousands had rushed to sign a junior doctor’s petition demanding that NHS workers be tested so they would know if they were safe to work or not, and officials said they were aiming for 25,000 tests a day.

Just a day later, the prime minister, Boris Johnson — who on Friday revealed that he had tested positive for the virus — claimed that daily testing would rise to 250,000. This week it has reached about 6,500 a day and officials said it would not reach 25,000 until the middle of April.

On Friday the government also announced that a new alliance of businesses, research institutes and universities would boost tests for frontline health workers, with hundreds to be done by the end of the weekend and numbers rising sharply next week.

So why did the government ease up on what initially seemed to be a concerted contact tracing and quarantining effort?

“There comes a point in a pandemic where that is not an appropriate intervention,” Jenny Harries, the deputy chief medical officer for England, told reporters on Thursday, adding that the testing focus had to shift to patients and then to health workers.

“There has been a plan right the way through this which is entirely consistent with the science,” she said, adding that if there were “infinite testing facilities”, the wider public could be included.

Yet even if the government had those infinite facilities, some people fear it has left it too late to find the chemicals and materials needed to boost its testing capacity.

“We moved to the delay phase; we then realised we wanted to suppress, but by that stage the whole world had woken up to the need for testing and we had to get in the queue,” said the senior Tory.

In the face of rising public concern about the lack of testing, Mr Johnson and his officials have begun to highlight work on a “game-changing” new antibody test that they hope will let people find out if they have had coronavirus and are therefore — hopefully — immune.

But it is still unclear when that test will be widely available.

Meanwhile, those who have worked on past epidemics say there is one clear lesson from the UK’s uneven testing approach.

“Whatever decisions people think they need to make, they need to make them quicker and bolder,” said virologist Professor Paul Kellam of Imperial College London, who has worked on swine flu, Ebola and other outbreaks.

In the UK, that probably meant taking a gamble on massively ramping up testing capacity at the end of January, he said, but he admitted that would have been a difficult decision.

Even so, he said, “it’s better to be big and bold and overshoot, than [be] late and under capacity”.

Letter in response to this article:

Common sense should be up there with the science / From Dr Tony Agathangelou, Brighton, E Sussex, UK

Comments