Starchitect Daniel Libeskind’s Christmas showstopper

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

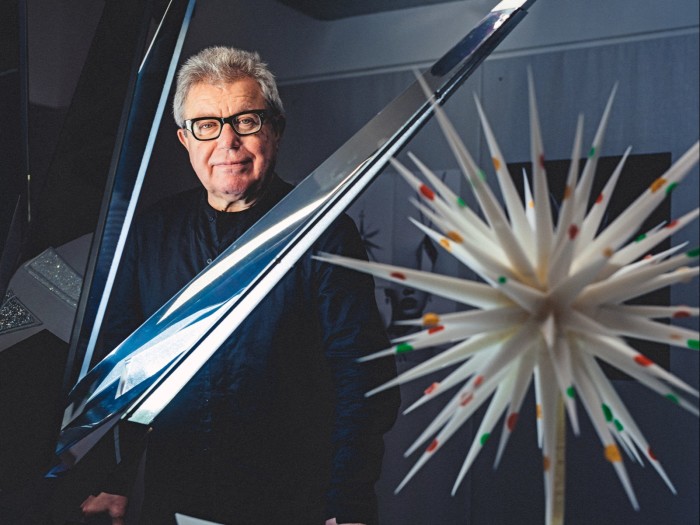

How perfectly fitting that architect, artist and musician Daniel Libeskind has designed the Swarovski Star for this year’s Rockefeller Center tree. The internationally renowned polymath has made a career from creating dazzling, dynamic forms apparently untroubled by the gravitational pull of the earth and edifices that foster contemplation and ultimately optimism. Oh, and he adores crystal.

“I’ve always gravitated to crystalline forms, from the Jewish Museum in Berlin (2001) to my master plan for Ground Zero in New York. Even my curvilinear buildings have a crystal quality, like the Imperial War Museum North (2002) and Reflections at Keppel Bay, Singapore [2012]. I’m not one for computer-generated blobs; I’m for geometry and mathematics, for the beauty of the perfect crystalline form.”

He first worked with Swarovski in 2016, on a sculptural chess set (£13,995 from Atelier Swarovski Home) representing skyscrapers he’d built. “I mixed New York and Milan, places I live and work in, and the pieces were crafted in different materials. It was a beautiful idea,” he says. When Nadja Swarovski invited him to reimagine “a vision of peace, unity and hopefulness” in crystal to serve as New York’s most famous tree topper, he was delighted to renew the collaboration. “I decided it should be a 21st-century star, so it’s kind of an exploding three-dimensional wow!” he explains. “It’s not perfectly symmetrical. It has a core almost like a Leonardo da Vinci core of light, which radiates into the tips of the star and has thousands of crystals that make the light amazing within these transparent rays.” Fans will be able to buy miniature spin-offs for their own trees: laser-etched Atelier Swarovski Home ornaments (£59).

Libeskind finds the symbolism of the star particularly inspiring. “My son is a cosmologist who deals with constellations and the Milky Way. I’ve learnt we are all made from stardust from the Big Bang – the elements in our bodies are made of stars. What a beautiful connection between peace, the holidays, us and the cosmos.” Connections are a Libeskind speciality. As he talks, he can create links between any two topics in the universe: Renaissance inventors and Christmas trimmings; the golden section (or ratio, as it’s better known) and rap music. To listen to him is to be taken on a philosophical joyride. Or, given the season, an intellectual sleigh ride.

The architect arrived in New York aged 13 with his parents, who were Polish Holocaust survivors. “I came straight from the boat into the Bronx – that makes me a New Yorker right away. Even now, you can hardly meet anyone born in New York,” he says. “America is a country of immigrants, whatever the rhetoric coming from politics.” The visionary behind the exhilarating extension to the Denver Art Museum (2006) did not start life intending to be an architect. From early on, he was a musician, whose speciality was the accordion. “It was only in time that I discovered that architecture connects all my interests – music, drawing and mathematics – things I’ve always loved,” he says. “It was a complete surprise. I don’t think I’d ever met an architect in my life before going to Cooper [where he studied architecture and gained his first degree in 1970]. I lived in social housing in the Bronx among working people. My parents worked in factories. I’d never known any so-called professionals. And I really did not know what I was getting myself into. But who doesn’t love to draw…”

Deyan Sudjic, director of London’s Design Museum, knows this side of Libeskind well. “Like Zaha Hadid, he first attracted attention for his brilliant drawings, most of which looked like abstract but dynamic compositions or even sheet music or concrete poetry,” he says. “Daniel Libeskind belongs to a generation of architects that started out in the 1980s, when ideas were seen as more than building for building’s sake.” The architect says that he never consciously adopted his remarkable style. “Good taste is a matter of choice, but style is a reflex. It’s not something you choose, it chooses you,” he states. Perhaps a clue to his visual virtuosity lies in this recollection of the monolithic Eastern Bloc architecture of his childhood: “One building that remains in my mind is a structure that I hated when visiting Warsaw with my parents – The Palace of Culture and Science, the palace that Stalin built to oppress the Polish people and stood as a monument to communism,” he says. “How lucky I was to be able to create a residential tower right across from that building. Złota 44 [a curvilinear skyscraper, completed in 2017] is a building that says the city does not belong to communism. It belongs to people.”

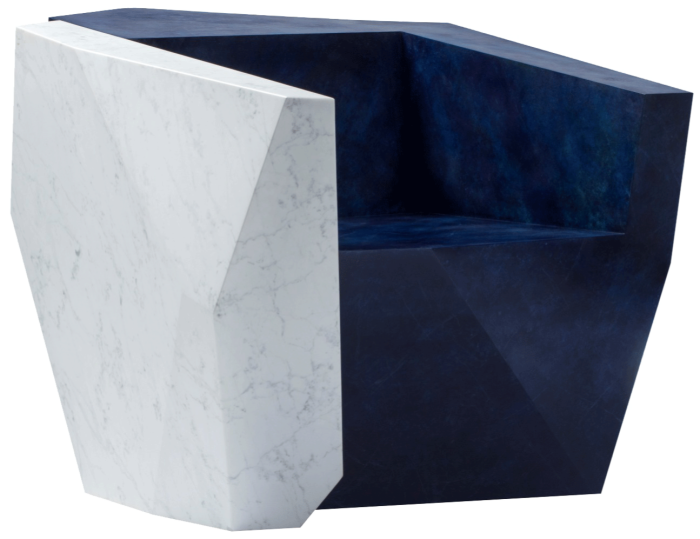

Libeskind never abandoned his early interests in art and music. “There are many lives within architecture,” he says. He created the installation Sonnets in Babylon for the Venice Biennale of 2014, and this year London’s David Gill Gallery held a solo exhibition of Libeskind’s design-art furniture made from bronze, marble, carbon fibre and stainless steel. The limited edition Fundamental Elements collection (price on request) includes a bronze coffee table entitled Megalith in Motion that appears as though hewn from rock, and a table with shards of flat glass panes recalling the zigzagging façade of his Jewish Museum. The armchairs, forged in marble and patinated bronze or stainless steel, are mesmerisingly multifaceted – a design that draws on the same geometry as his gemstone-like Gemma sofa (£7,776) and armchair (£3,120) for Moroso in 2015.

Music is such a passion of his that he argues all his work is musical. “Architecture and music are very closely related,” he says. “When you design a building you have to write a score, an architectural score. In the end, music and architecture have to speak to your soul.” He is a musical omnivore who devours new sounds discovered via Spotify and his artist daughter’s musician friends. His taste ranges through “opera, classical, orchestral, contemporary, popular, world and rap music”. It hurts him to name favourites. “Oh no, it’s like saying ‘What’s your favourite colour?’. I say the rainbow!” he exclaims. “But I do listen a lot to the works of Bach. Jazz? Absolutely, Thelonius Monk, Miles Davis… A favourite rap star? Jay-Z is great.”

His own greatest hit, the building he will forever be remembered for, is the Jewish Museum. He won a competition to design it in 1989 and completed it in 1999 (ahead of its 2001 opening). It is a work of brilliance, both meditative and mercurial, with a zigzag floor plan and zinc-clad flanks. Rory Hyde, curator of contemporary architecture at the V&A Museum, describes it as one of the architectural masterpieces of the 20th century. “It manages to express the inexpressible trauma of the Holocaust through building,” he says. “It’s this leap between meaning and form that is so significant about Libeskind’s work.”

The museum marked a crossroads in Libeskind’s life. He was awarded the commission while living in Milan, where he had founded the Architecture Intermundium – Institute for Architecture & Urbanism. At the time, he had been offered a scholarship at the Getty Center and was about to move his family back across the Atlantic. “We were on our way to LA, an income, a house in Santa Monica, and stopped in Berlin to pick up the award. There was one road that led to a nice life in LA or another where we stayed in Berlin. I asked my wife what she thought. I said if we stayed, it was on condition that she became my business partner.” He founded Studio Libeskind in 1989 with Nina, now his wife of almost 50 years, as COO, and settled in Germany to oversee the project of a lifetime.

During the months before the Berlin museum opened, Libeskind’s Eighteen Turns Serpentine Pavilion of summer 2001 was creating a stir in London. In those days, the temporary pavilion in Hyde Park was still a novel installation rather than a venerable annual fixture in the international design calendar. Libeskind’s “architectural origami” of aluminium panels set the agenda for future contributors. “It arguably put the Serpentine Pavilion commission on the map after Zaha Hadid’s inaugural structure,” says Hans Ulrich Obrist, current artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries. It had taken Libeskind just two years from the completion of his first building, finished in 1999 when he was 53, to become one of the hottest architects in Europe.

Two days after the Serpentine Pavilion closed in London, and on the very day that the Jewish Museum in Berlin was due to open its doors, came the catastrophe that would draw the architect back to America – the 9/11 attacks. “Many of the projects that I’ve been involved in were memorials, museums with difficult histories like the Jewish Museum, the Imperial War Museum in Manchester and the German Military History in Dresden,” he says. “Many deal with difficulties, wars, catastrophes and deaths and the question is how do you balance memory and something that affirms life. That’s the great task of these spaces – the victory of life over evil is the aim. We know from psychology that you can’t get rid of traumas by repressing them; you have to confront them in some way and do something positive.” In 2003, Libeskind moved his studio to New York, having won the competition to create the Ground Zero Master Plan, redeveloping the World Trade Center site.

At present, having finished a book on his creative process (Edge of Order, out November 27, $80, Clarkson Potter), he is concerned with the future of cities and how to make them more environmentally friendly and socially equal. He is planning a development of affordable housing for the elderly in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where building work will start in 2020. It’s not a sexy mega-project that will get him onto magazine covers, but, as he protests, “I’m not the kind of architect who lusts after bigger and better projects. Architecture isn’t about how much money you have. You can create a dignified and beautiful environment for people to live in with a limited amount.” He is also working on a new Maggie’s Centre at the Royal Free Hospital in London. The centres were founded in memory of Maggie Keswick Jencks and express her belief that people should not “lose the joy of living in the fear of dying”. Charles Jencks, cultural theorist and co-founder of Maggie’s, is a good friend as well as an admirer of Libeskind’s work and is thrilled to add him to the roster of venerable architects who have created the centres, including Richard Rogers, Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid. “Studio Libeskind’s optimistic designs sit well with our ethos,” he says.

Libeskind’s own recipe for wellbeing is quite unexpected. Does he work out? Cook? “I can only cook an egg,” he says. “One of the things I do, which is my way of relaxing, is memorising poetry. Emily Dickinson is one of my favourites, and Shakespearean sonnets and soliloquies. The human mind is an empty chamber. You need some furniture in the brain that you can rely on, so you’re never bored. When I’m flying, I don’t have to watch a movie; I can recite a sonnet. He begins Sonnet 116: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds…” For someone who has created memorials to the major human tragedies of recent history, Libeskind is remarkably light of spirit. He is looking forward to Christmas. “I’m Jewish, so I celebrate it as a wonderful secular worldwide holiday – one hopefully with snow. Snowflakes are another form of crystal, by the way…”

Atelier Swarovski, atelierswarovski.com. David Gill Gallery, davidgillgallery.com. Moroso, moroso.it. Studio Libeskind, libeskind.com

Comments