All eyes on Lagos: an artistic homecoming

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In a new white-cube gallery in Lagos, monumental nude self-portraits by the British-Nigerian artist Joy Labinjo line the walls, her body transformed into a vast undulating patchwork landscape. In this conservative country, it’s a bold gambit to open a space with a show of nude paintings, but risk-taking is nothing new to the London gallery Tiwani Contemporary, which has made its name championing artists from Africa and the diaspora. Now, to celebrate its 10-year anniversary, Tiwani has launched a purpose-built 2,000sq ft space on Victoria Island, Lagos. For its founder Maria Varnava, a Greek Cypriot who grew up in Nigeria, it amounts to a homecoming.

“This was always my dream,” says Varnava, a glamorous figure with an infectious energy. “The plan was that at 10 years, if we were in a good place in terms of our reputation and positioning, we would go for a second space.” In the past decade, the gallery has gained a reputation for spotting nascent talent: it exhibited Simone Leigh and Njideka Akunyili Crosby back in 2013 (the former will represent the United States at this year’s Venice Biennale, and the latter appeared in a group exhibition curated by Ralph Rugoff at the previous 2019 Biennale). Today, Labinjo is one of several rising stars on Tiwani’s 15-strong roster, including Andrew Pierre Hart, who makes ravishing mixes of paintings and soundscapes, and Charmaine Watkiss, whose beguiling drawings evoke themes of African cosmology, tradition and ancestry. Yet whereas other gallerists might have opted to open a new branch in New York or Paris, that made no sense for Tiwani, whose name loosely translates as “it belongs to us” or “it’s ours” in Yoruba. “I work with artists from Africa and the diaspora,” Varnava notes, “and I think for the long-term sustainability of what we’re doing, we need to engage with the local patronage. We need more collectors from Africa and the diaspora.”

It wasn’t always Varnava’s plan to run a gallery. She left Nigeria for Cyprus aged 11, although her family retained a base in the country. “I grew up with the visual language of Nigeria and it was very inspiring. Nigeria has had such an impact on my world view.” Later, when studying history of art at Glasgow University, she was shocked to find that artists from Africa or even from the diaspora were virtually absent from the curriculum: “I remember studying the Renaissance, the baroque period, reading all those books and nobody was mentioning what’s happening back home in Nigeria.” When the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2004, Varnava was so excited that she wrote him a fan letter. “It was very naive, but definitely heartfelt,” she smiles, blushing at the memory.

A few years later, after four years of working at Christie’s, Varnava left to do a masters in African studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies. During a trip to Nigeria she met with the late curator Bisi Silva, who had founded the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) Lagos in 2007 and would become a close friend and mentor. “I was thinking of organising a publication, or a pop-up exhibition, something very humble, and Bisi said, ‘Listen, Maria, if you want to do something impactful, then you need to set up a gallery in London,’” Varnava recalls. “I remember going home and telling my father, ‘Right – I’m starting a gallery.’”

Tiwani was not the first or only gallery in London to show African artists – October and Jack Bell had already paved the way. But when it opened in 2011, it was perhaps the first commercial space with such a clearly defined mission to broaden the representation of contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora, and it has wielded influence way beyond its small size. “It was quite important to have a venue such as that in London, that was dedicated primarily or solely to art from the continent,” confirms Portia Malatjie, the adjunct curator of Africa and African Diaspora at Tate Modern. In 2012 Tate founded its African Acquisitions Committee; the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair arrived in London in 2013; and The Courtauld last year announced appointments in modern and contemporary art with specialisms in Black studies and critical race art history.

Meanwhile, Nigeria has developed a local art market, as seen by the success of Art X Lagos, an art fair launched in 2016 that last year hosted 120 artists from 30 galleries. Besides that, there’s also LagosPhoto, a month-long photography festival, the CCA Lagos and the Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, named after one of Africa’s foremost collectors. Shonibare is also fostering artist residencies and cultural exchange under the banner Guest Artists Space Foundation.

“There’s a very strong community of artists and a growing community of collectors,” says Tokini Peterside, a Nigerian entrepreneur and founder of Art X Lagos. “Having a gallery such as Tiwani come onto the scene only helps to strengthen it, but also signals to others that there is tremendous potential here just waiting to be harnessed.”

The gallery itself is embedded in the heart of the thriving Victoria Island, home to local galleries, designer shops, restaurants and exclusive clubs (see below). Located within a gated compound, it has a discreet presence, merging with the leafy streets. An airy reception with interiors by the Nigerian designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello leads to the exhibition space, a 12m x 12m room with 7.5m-high walls and an attractive ceiling with exposed white-painted steel beams. Outside, a lush patio area filled with plantain and papaya trees is envisaged as a space for experimental performances, talks and film viewings – the white gallery exterior offering a perfect backdrop for screenings.

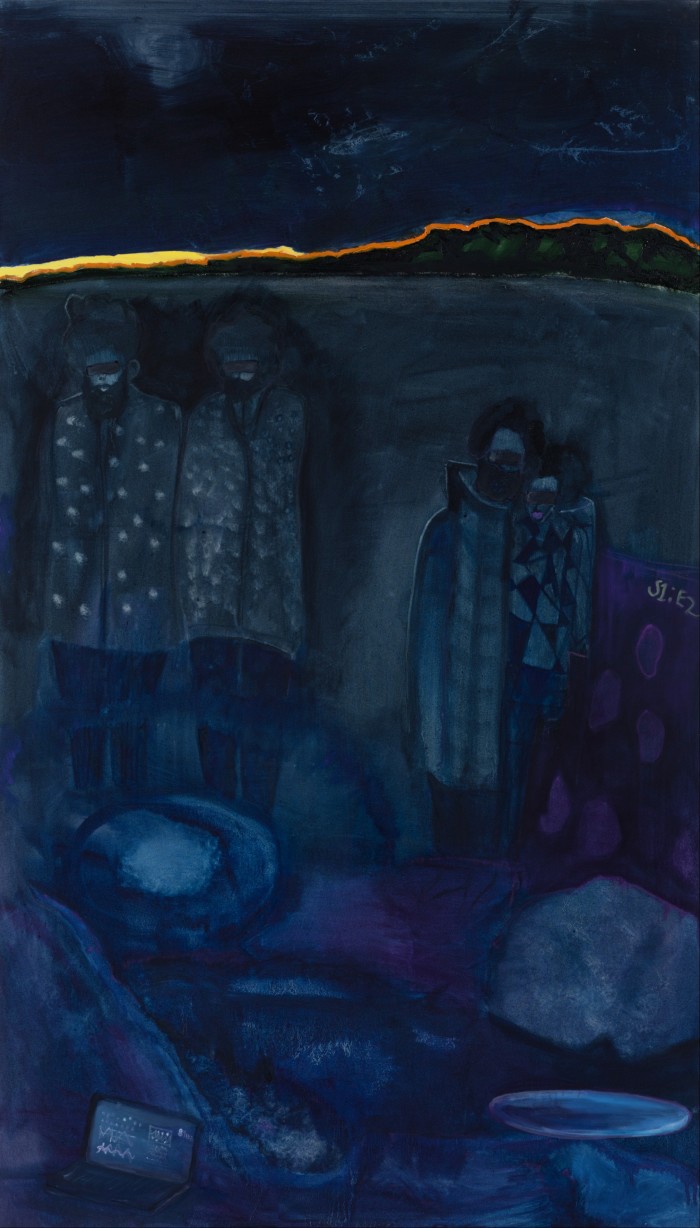

Its inaugural show Full Ground, which opened last month, marks a departure from the vibrant figurative paintings addressing issues of race, identity, family and history for which Labinjo, 27, is already known. “I was considering going back to family portraits as an ode to my parents, because it is a homecoming [for them] as well. They grew up in Nigeria,” says the London-born artist. “But it felt very safe.”

Having only ever visited Nigeria on family holidays and never “as Joy the artist”, Labinjo says she’s excited to be introduced to the art scene there and “very proud” of Varnava. “It’s an amazing opportunity – and also feels like a bit of pressure.”

She admits she was a little apprehensive about presenting a show of nudes. “I feel like we see nudity and sexuality a bit differently to how it’s seen in Nigeria. My experience of being there was being told every time to cover up.” “But I think the nudes are an entry point into discussions. And the female body, to me, isn’t something to feel ashamed about.” Moreover, Nigeria has a history of women using their naked bodies to protest against abuse of power, so these nudes carry added resonance.

Tiwani’s Lagos team on the ground is still being finalised (Varnava is “mindful of local complexities”). The goal is eventually to stage seven shows a year and to implement a rigorous programme of publications and talks. Varnava hopes Tiwani’s presence will give local art students the chance to experience international contemporary art in person rather than online or in publications. “I’m entering the contemporary art scene in Lagos very respectfully,” she says. “This is a long‑term commitment.”

But the main challenge will be to help to nurture and build an African collector base. Labinjo’s paintings typically sell for £60,000 – Varnava says the programme thereafter will offer a range of prices to appeal to a broad demographic. “The exciting space is collectors in their mid-30s and 40s who are increasingly affluent through their work in Lagos, and are becoming much more active as art collectors,” says Tokini Peterside.

And once Tiwani is established in Lagos, Varnava plans to reach out to dynamic arts organisations that are springing up on the continent. “My long-term vision,” says Varnava, “is to contribute to and create more of those encounters in a pan-African context.” The meaning of Tiwani – “it belongs to us” – has never seemed truer.

An insider’s guide to Nigeria’s largest city

By Maria Shollenbarger. Additional reporting by Enuma Okoro

Lagos is Africa’s second-largest city, a thriving financial hub that has incubated a large and ambitious new middle class. It’s also emerging as a west African cultural capital, with local artists and creatives intersecting with reverse-diaspora benefactors and scene-makers.

The action tends to centre on Victoria and Lagos Islands. The 61-room George Hotel, in the plush Ikoyi neighbourhood (which adjoins Lagos Island), is a favourite with business travellers, with green surrounds and wide terraces. A few blocks to the east is The Wheatbaker, a slightly buzzier iteration of business-luxury, with a lap pool and a small spa.

Calling itself west Africa’s first concept store and dedicated largely to fashion, design and crafts produced in the region, Alára is an eye-catcher: the striking black-and-red building, on an elegant Victoria Island street, was designed by David Adjaye. There’s Louboutin and Saint Laurent, but also furniture by Burkina Faso-based Hamed Ouattara, fashion by Nigerian 2019 LVMH Prize finalist Kenneth Ize and a programme of trunk shows, exhibitions and even the odd speed-dating night.

Next door is Nok, the modern restaurant opened by Alára’s founder, Reni Folawiyo – its reinterpretations of African classics have made it one of most popular tables on Victoria Island. The other to try is Slow, a slick tropical-hothouse venue that borrows heavily from Latin-American traditions and a little from Middle Eastern-Mediterranean ones (and grows much of its own veg hydroponically). On the menu are spiced lamb and labneh flatbreads alongside brisket tacos and various ceviches.

In the same building, Temple Muse casts a more international net than Alára (think Orlebar Brown, Lemlem, Cire Trudon), but also champions local fashion talents like Ituen Basi and Kadiju. And the much-loved music store/bookstore/performance venue that is The Jazzhole is a must. Opened in 1991 by Kunle Tejuosho, whose mother founded the Glendora bookstore chain here, it specialises in cool vinyl, obscure monographs on Afrobeat and, in its little café, some of the best coffee in town.

Nike Art Gallery is among the city’s best-known addresses overseas: founded in 2009 by textile artist Nike Davies-Okundaye, today it has, besides the Lagos mothership, outposts across the country. Its five storeys showcase collectable paintings, a textile museum collection and the requisite café.

Newer and more directional is Angels and Muse, where the mission is to be a “thought laboratory” for art, literature and more. The multipurpose HQ, founded by Nigerian artist-writer-photographer Victor Ehikhamenor, hosts a gallery, co-working space, events rooms for workshops and a vibrant residence for short-term stays. The suite, designed by Ehikhamenor, is a chromatic riot – and has to be one of the coolest sleeps in Nigeria.

Comments